You’ve probably heard the complaint before: craft beer is becoming monotonous, it’s all about IPA, most breweries just brew hazy bois with a few fruited sours and pastry stouts sprinkled in between, and if they feel extra special, a West Coast IPA. This is usually refuted with the argument that brewers just brew what pays the bills, it’s what people want to drink, etc., which is again countered with lamentation that other beer styles are dying out (ok, a bit hyperbolic) because nobody brews them anymore.

This is not a new phenomenon.

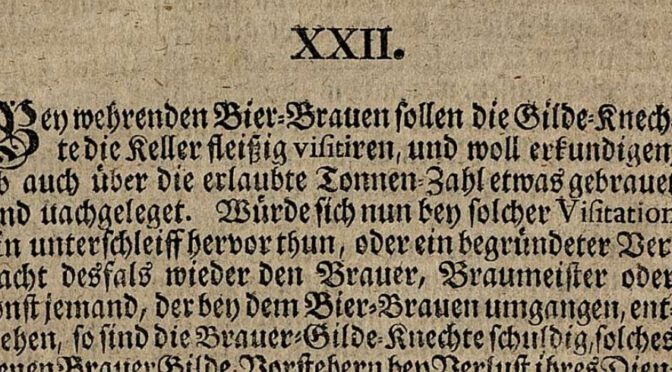

150 to 200 years, German beer and brewing experienced a massive shift. Small breweries were previously mostly brewing relatively small amounts of beer solely for the local market using little to no automation, brewers were organized in guilds, not interested in scaling out their businesses, and sometimes even bound by local law to brew and sell their beer on a rota (Reihebrauen). Then the industrial revolution came and destroyed a lot of these structures.

In some cases it was young brewers with an entrepreneurial spirit taking over from their fathers and looking to expand and grow it using modern technologies, in others it was simply trained brewers backed by money to start entirely new brewing companies with all the latest equipment and scientific knowledge to brew excellent beer.

Bottom-fermented beer became fashionable, and due to how it was produced and stored (at cold temperatures with a yeast that increased the sulphur content of the beer, two factors contributing to a more stable beer) the beer became more suitable for export. Export in this context simply meant shipping it further than what was the common “local” area, but innovations like the railroad made it possible to ship beer quite a bit further, and with the invention of ice waggons, some breweries were even able to establish proper cool chains (a famous example for that is the Dreher brewery in Kleinschwechat near Vienna which shipped ice-chilled lager beer from their brewery to the Paris Expo 1867, one delivery took just 5 days and was kept at a constant 4°C). The beer tasted clean, fresh and properly quenched the thirst of beer drinkers.

People started craving this fashionable beer, so naturally, the market adjusted to it, beer legislation was liberalized, and more brewers had the opportunity to enter the market and brew bottom-fermented beers. At the same time, the old-time breweries where “local beer for local people” had been brewed for hundreds of years, didn’t have the money to upgrade their equipment to brew these new-fangled beer styles, or even to make smoke-free malt like the new lager breweries were doing it.

Within just a few decades, a lot of small, local breweries simply shut down because they couldn’t compete, and local beer styles (German brewing literature at the often spoke of Lokalbiere) simply went extinct because nobody wanted to drink them anymore. A lot of these beers we only know by name these days, a few have been preserved in the form of recipes, though a lot of details like how specific malts were prepared are not so well documented, leaving more questions than answers.

When we look at Germany, which beer styles are prevalent (because craft beer is really just a teeny tiny 1% segment of the whole market) and which of these beer styles are from before the industrial revolution, it becomes apparent how bleak it really is.

To the best of my knowledge, the list is really short: Berliner Weisse, Bavarian Weißbier, Altbier and Kölsch (I like to group them as Rhenish Bitter Beers or Top-Fermented Lager Beers because they are more similar than different though people from Düsseldorf and Cologne may hate me for that), Leipziger Gose, and Bamberger smoked beer, and some of them did not fare too well in the last 70, 80 years and were only just rescued from dying out.

Berliner Weisse was still brewed by a few breweries in both East and West Berlin after World War 2. The biggest shock was probably when Schultheiss stopped brewing their traditional unboiled mixed-fermented version. Berliner Kindl Weisse, a very industrial beer brewed by fermenting a low-alcohol beer normally and blending it with another batch that was just fermented with lactic acid bacteria and then sterile-filtrated, thus became the only available brand on the market. In Berlin, the style was really only rescued by a few craft brewers, such as Andreas Bogk, BrewBaker, Lemke, Schneeeule, Berliner Berg, Vagabund, and others, who specifically intended not to let this piece of beer history die out.

Bavarian Weißbier was already a niche product when it again became permitted for private Bavarian brewers to brew with wheat again, and it only survived because of a relatively small group of connoisseurs, until the 1960s when it suddenly somehow became more fashionable again and thus had its revival.

Altbier and Kölsch were not particularly popular during the interwar period, and really only regained popularity after World War 2: Kölsch as it was marketed as a genuinely local beer, appealing to the hyperlocal patriotism in Cologne, while Düsseldorfer Altbier apparently only regained popularity in the 1960s. Münstersches Altbier, another Altbier style, really only exists in the form of one brewery, Pinkus Müller.

Leipziger Gose was actually functionally extinct from the early 1960s when the last Gose brewery shut its doors until the mid-1980s, and it could only be rebrewed and revived to its original taste because the East German brewers producing it could have it taste-tested by beer drinkers who still remembered it from before the 1960s.

And finally smoked beer. Even in Bamberg, this is kind of a niche product. Of the more than 10 breweries that are still around, only two still make their own smoked malt to brew their very own smoked beer, Brauerei Heller (Schlenkerla) and Brauerei Spezial. Greifenklau stopped their own kilning operation in the early 1970s, but fortunately is still around. Nowadays, they brew some smoked beer as a seasonal product, but their owning malting and kilning operation is long gone. And Polarbär brewery, which I like to call the fourth Bamberg smoked beer brewery isn’t operational since the 1950s or so.

And yet, none of these beer styles are truly extinct or even remotely in danger of going extinct. Why? Simply put, thanks to craft beer. Starting in the US, but now really all over the world, there are countless beer nerds who truly care about these old beer types, some rebrew them at home, others brew them commercially, making these beers that were definitely at the brink of extinction better known to beer drinkers all around the world.

Yes, there is some truth that IPAs and hazies are taking over, and yes, some breweries certainly struggle with that problem, because it’s what pays the bills. “The customer is king”, and it would not make sense economically to brew a beer that would not be as popular and thus not sell as well. In the end, IPAs keep the other styles afloat, as the money earned through them gives brewers some freedom to also try out other styles. Styles that used to extremely local to just small regions of Germany have now gained worldwide fame. Even 50 years ago, this probably would have been mostly unthinkable.