Some time ago, my wife and I started collecting Steinkrüge, German-style stoneware mugs for beer drinking. I don’t know what exactly started our interest, but what played into it was a historic Steinkrug of Franziskaner-Leistbräu that I got to photograph for my most recent book about Vienna Lager.

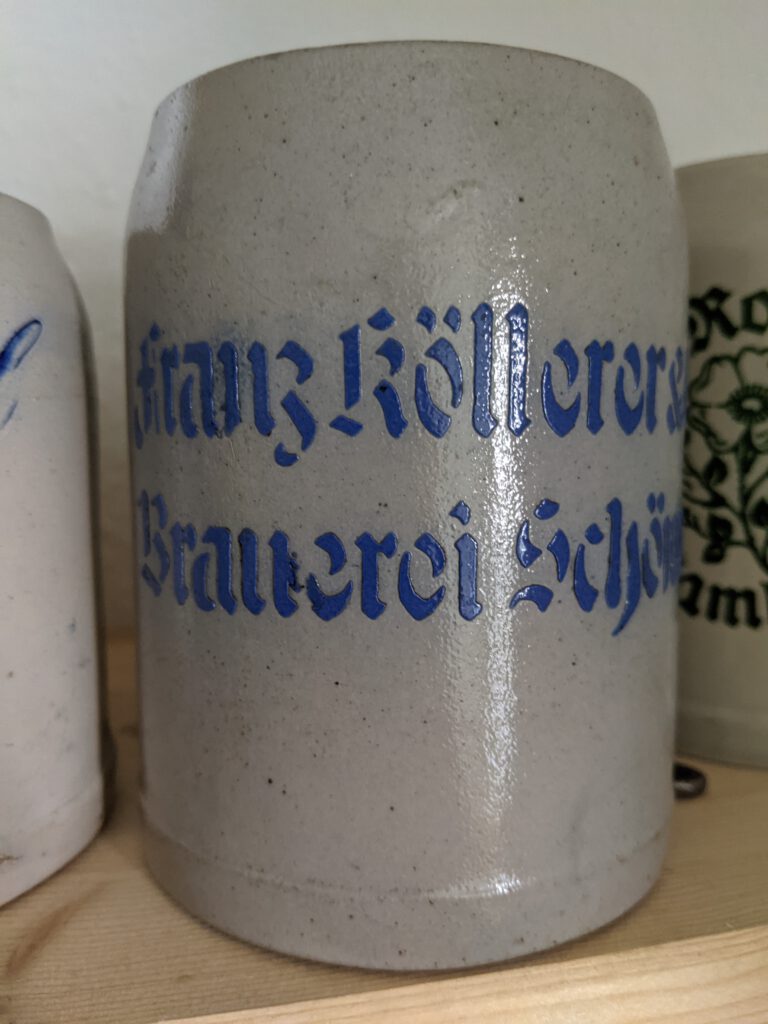

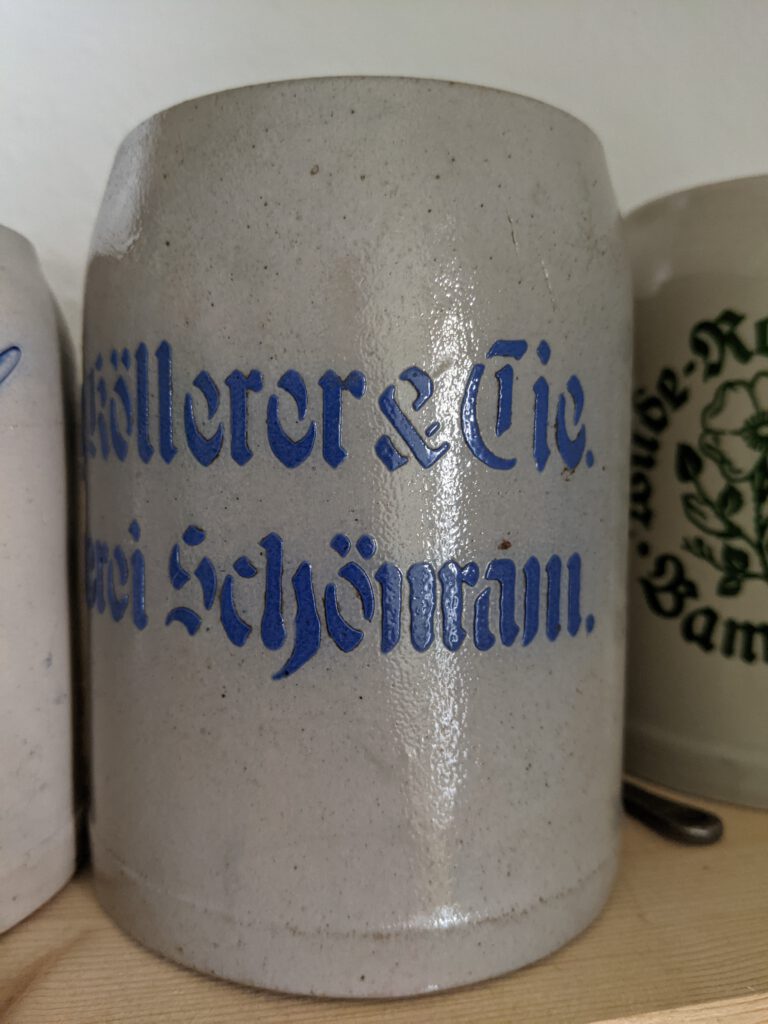

Most recently, we managed to win an online auction for a historic Steinkrug of one of our favourite breweries, Brauerei Schönram located in the Bavarian municipality of Petting, in particular a small settlement of it called Schönram. The Steinkrug that we got said “Franz Köllerer & Cie Brauerei Schönram” on it. From Schönramer’s own history on their website, I knew that the Köllerer surname has been connected with the brewery since 1780, the brewery’s official year of foundation when Jakob Köllerer bought the place, and only changed shortly before World War 2 when a daughter from the Köllerer family, Lisa, got married to Alfred Oberlindober.

So who was Franz Köllerer, and what does “Franz Köllerer & Cie” mean anyway? That whole thing got me down a bit of a rabbithole when I checked all my usual sources to see what I was able to find.

The earliest person named Franz Köllerer that I was able to identify was Franz Seraphim Köllerer, born on Sept 14, 1839 in Schönram. The Köllerer family must have been reasonably wealthy, as Franz was able to attend grammar school in nearby Salzburg. Schönram and Salzburg had been well-connected for quite some time, as Schönram was located on postal routes between Salzburg and Munich as well as Salzburg and Regensburg. According to a 1815 post manual for the kingdom of Bavaria, the local postman in Schönram was a certain Anton Köllerer.

Another sign of Franz Köllerer’s wealth is how well-travelled he was. Not only can his name be found in public records that he stayed in Salzburg, Linz and Graz several times during the 1860s and 1870s, a book titled “Deutscher Parlaments-Almanach” (German Parliament Almanac) credited him with having travelled abroad to Hungary, the principalities along the river Danube, Turkey, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Greece and Italy.

“Why would he be mentioned in such a book?”, you wonder. Very simple: because he got elected as Member of Parliament to the German Reichstag in Berlin in 1874, for the district of Rosenheim, a role in which he served until he stepped down in 1877. According to Salzburger Chronik in 1874, he was “not a studied man” but a well-known man with a “healthy heart and mind from the midst of the German people”.

During his time as brewery owner, Brauerei Schönram must have been at a reasonable level of modernization. In 1870, it is cited as only one of two breweries in the region to have any sort of automation going on. In particular, the brewery had a steam engine, which not only was used for the brew kit, but also for crushing the malt. The brewery used an annual amount of about 2000 Scheffel of barley. The amount of beer that could be brewed from a certain quantity of barley was strictly regulated in Bavaria at the time, so we can roughly estimate how much beer was brewed annually, and it must have been roughly 7000 to 8000 hl. This is remarkably consistent with Schönramer’s “official” history on their website, which states that between 1900 and the 1960s, the brewery steadily produced about 7000 hl of beer every year.

Half of the barley that the brewery used was from the area, the other half was imported from Innviertel (Upper Austria), Moravia and Hungary. The hops that were bought were from the Bavarian hop regions as well as Bohemia, and more than 50 Zentner (2500 kg) were used every year. From that we can also derive the rough hopping rate of the typical beer brewed at Schönram, at 3 to 3.5 g/l.

Franz Köllerer died on January 26, 1879, in Schönram.

I was also able to find out about another Franz Köllerer. Unlike the previous one, he was indeed a studied man, an alumnus of Weihenstephan brewing school in 1894/1895. When he joined the alumni club of “Weihenstephaner” in 1903, he was credited as brewery owner in Schönram. He died from a stroke in 1915, aged only 41, which would make his year of birth 1874 or 1875. I haven’t been able to find out about how he was related to Franz Seraphim Köllerer, but it wouldn’t be unlikely if he was his son.

Franz Köllerer wasn’t the only brewery owner at the time, though. We know this because on August 1, 1900, the firm “Franz Köllerer & Cie Brauerei Schönram” was registered as a partnership, with a total of five business partners: Franz Köllerer, Anton Riedler, his wife Maria Riedler, and Wilhelmine and Seraphine Köllerer, the latter two described as adult brewery owner daughters. Judging from Franz Köllerer’s age, Wilhelmine and Seraphine were likely Franz Seraphim’s daughters.

And this is where we have the exact company name that is also on our Steinkrug. This at the very least helps us date it to the year 1900 or later.

After a bit of searching, I finally also understood was the “& Cie” stood for, it was short for “Compagnie”, and was used as a suffix for a particular type of company that was comprised of more than two business partners (five in Brauerei Schönram’s case). Nowadays, the suffix “& Co” would be more common in Germany.

Another partner, Anton Riedler, died in 1923, but only a few years later, in 1926, a new business partner makes his appearance in historic sources. Rudolf Nebinger, an Austrian retired cavalry officer of the Landwehrulanenregiment 4 stationed in Olomouc and veteran of World War I at Austria-Hungary’s Eastern front, who got engaged to Elsa Köllerer in 1917. His armed forces service is better documented than his work as brewery owner: in a registry book of regimental officers in 1911, he appears as First Lieutenant, when he got engaged in 1917, he had been promoted to Rittmeister (the cavalry’s equivalent to Captain), and he retired at some point, presumably at the end of World War I, as Lieutenant Colonel.

As a brewery owner, Rudolf Nebinger was wealthy enough to pay for a 30 meter long plane hangar at the newly opened Bad Reichenhall airfield in 1926. He died on October 18, 1934, from a heart attack.

Besides the brewing business itself, the brewery also owned a number of tied hotels and pubs, as well as land. Abtsdorfersee, a lake with an island near Schönram, was sold by the state to the brewery owner in 1869 for 3300 Gulden. The brewery ran a kind of pub or hotel there, named “Seebad”, which sounds like it was part of a lido. It burned down in February 1924, but was rebuilt and reopened in May 1927.

Another location they owned, Hotel Krone in Freilassing, also fell victim to fire: in the night of March 25-26, 1922, a defective oven caused the building to catch fire. Even the fire brigade from nearby Salzburg had to come and help extinguish.

Hotel Bavaria in Bad Reichenhall was also owned by the brewery and opened in 1890. They also owned two local train station restaurants, one in Piding (sold in 1926 to business man Matthias Schöndorfer), the other one in Hammerau.

And that was all I was able to find out in a few days research. While not representing a complete history of Schönramer brewery, I was still able to highlight a few more details about the owners over time, and in particular, was able to shed some light on the particular text on our Steinkrug.