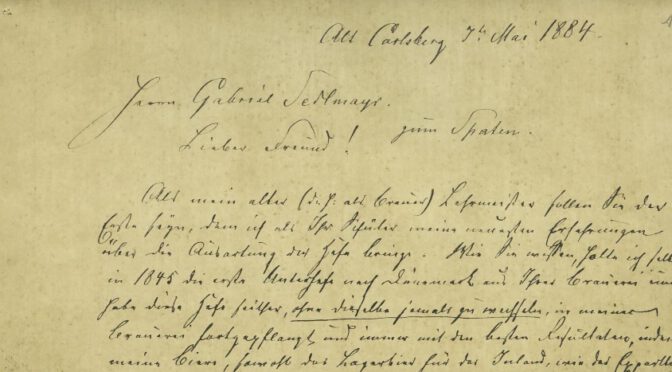

There is another letter from 1884 I came across in the J.C. Jacobsen archive of the Carlsberg Foundation, in which J.C. Jacobsen proudly tells Gabriel Sedlmayr of Spaten about his new pure yeast. I found it fantastic from a historic point of view because it gives insight into the circumstances, the background and what they thought was important about this new method of generating pure yeast. If you can read German, please directly read the original source, otherwise this is what J.C. Jacobsen had to say about this yeast:

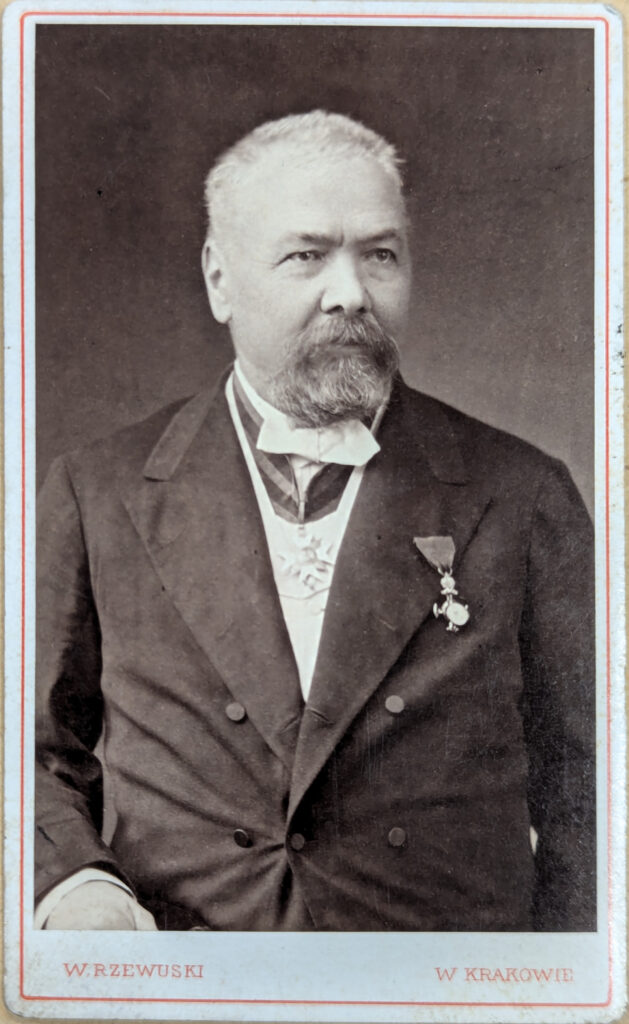

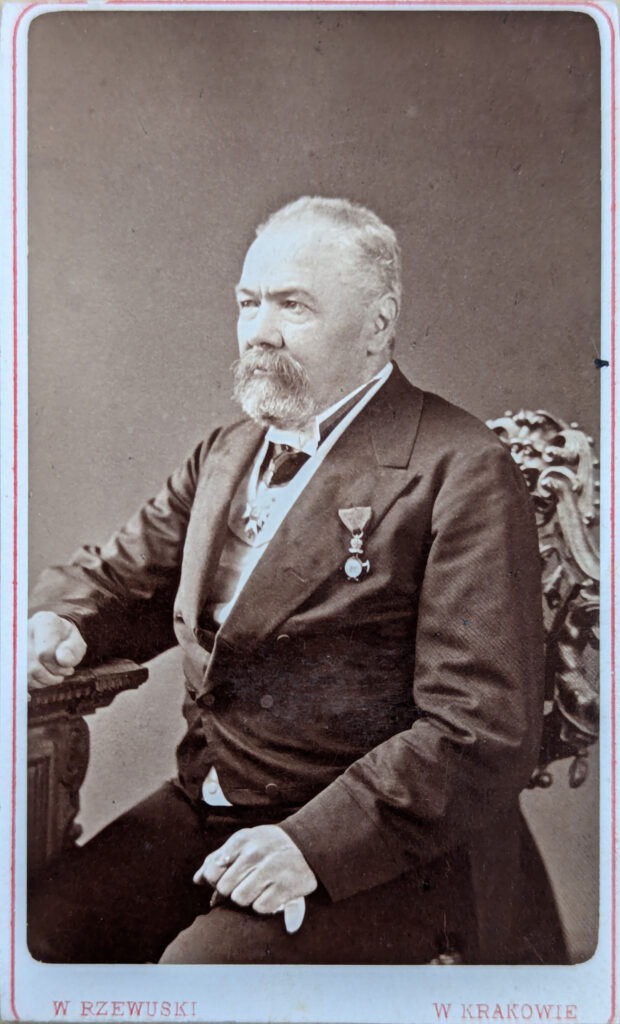

J.C. Jacobsen called Gabriel Sedlmayr his “old master teacher” and thus should be the first one to learn about his new experiences in the deterioration of yeast.

Jacobsen brought his first bottom-fermenting yeast from Sedlmayr’s brewery (i.e. Spaten) to Denmark in 1845 and had used it since then without ever having to change it, all while producing excellent lager beer for the domestic market as well as export beer for export to India.

Only in last two years (i.e. since 1882) the brewery started having quality problems and their pitching yeast started getting contaminated by “wild cells”. So of course Jacobsen asked the question why he could keep the same yeast from 1845 until 1882, only for it to deteriorate since then? Nothing has changed in the brewhouse and the cellars, they are cleaner than ever, wort is always chilled rapidly and even the air is cleaned with a spray of ice cold salt water that filters it the point where it’s analytically clean. Even the malt is of fine quality.

The only change was that due to an unexpectedly high demand and insufficient capacity, he had to resort to brewing during more months of the week: until 1874, Carlsberg only brewed in 7 to 8 months “the old Bavarian fashion”, and until 1882, brewing was still limited to at most 9 months, from early October until late June. But from 1882 onwards, this had to be expanded to 12 months as the lagering cellars that were to be built weren’t finished yet.

And exactly these 3 more brewing months were the problem: in the gardens and fields in the wide vicinity of Carlsberg, lots of fruits were ripening during that time, in particular cherries, plums, pears and grapes, which came with a higher amount of fermenting microorganisms, some of them bacteria, others wild yeasts like Saccharomyces Pastorianius (sic!). These led to increased infections on the coolships, in particular since wild yeasts like S. pastorianus kept growing together with the other yeast.

The last few sentences are particularly interesting, as Jacobsen seems to use the “Saccharomyces Pastorianus” name to describe wild yeasts, not bottom-fermenting yeasts which would be the modern use of the name. Later in the letter, he uses “Saccharomyces cerevisiae” to describe the regular yeast at his brewery. This is something I’ve not came across, but seems to indicate how little the specific nature of bottom-fermenting yeast was understood at the time before single yeast cells were isolated and analysed.

Jacobsen then continues by explaining Hansen’s method of isolating single cells in Pasteur flasks (swan-necked flasks), and how Hansen had isolated one pure Saccharomyces cerevisiae as well as two wild yeasts, which, when propagated and used for fermentation, all produced very different-tasting beers.

The pure S. cerevisiae was then used as pitching yeast in the brewery and effected a “nice fermentation” that quickly clarified, with a suitable attenuation from 13.5% to 6-7% Balling and quickly clarification and the maturation casks. Jacobsen then proudly proclaimed that “from now on all the fermentation in my whole brewery will be done with this pure yeast, created from a single cell! Truly a triumph of scientific research!”

He also pointed out that because of these observations, he thought that the yeast in all breweries is somewhat infected with “more or less wild” yeasts, as at the time most breweries were brewing during the summer months, and even regular yeast changing brings no improvement to that.

Jacobsen also notes that “in the old days”, when no brewery in Bavaria would brew during the summer, changing yeast was also a rare occurrence. If breweries wanted to continue brewing during the summer, then at least a few breweries or research stations like Weihenstephan or Dr. Aubry in Munich should occasionally isolate Saccharomyces cerevisiae to create pure yeast.

He also announced to to Sedlmayr that he’d send him a sample of enough yeast for one fermenter as express freight so that he could get acquainted with it. Jacobsen hoped it would arrive in Munich in a good state, though he admitted he had no experience sending yeast on such a long journey, and would be happy to send him more of his surplus yeast in the future.

The yeast also came with information how it was used at Carlsberg: the yeast was pitched at 5°R (6.25°C). The temperature increased to 6.5 to 6.75°R (8.12-8.43°C), and then slowly subsided back to 4 to 5R° (5-6.25°C). A 13.5% Balling wort fermented down to an attenuation of 6-7% Balling within 10 to 11 days. Jacobsen also pointed out that Sedlmayr’s wort contained less maltose than his own, so Sedlmayr had to expect lower attenuation.

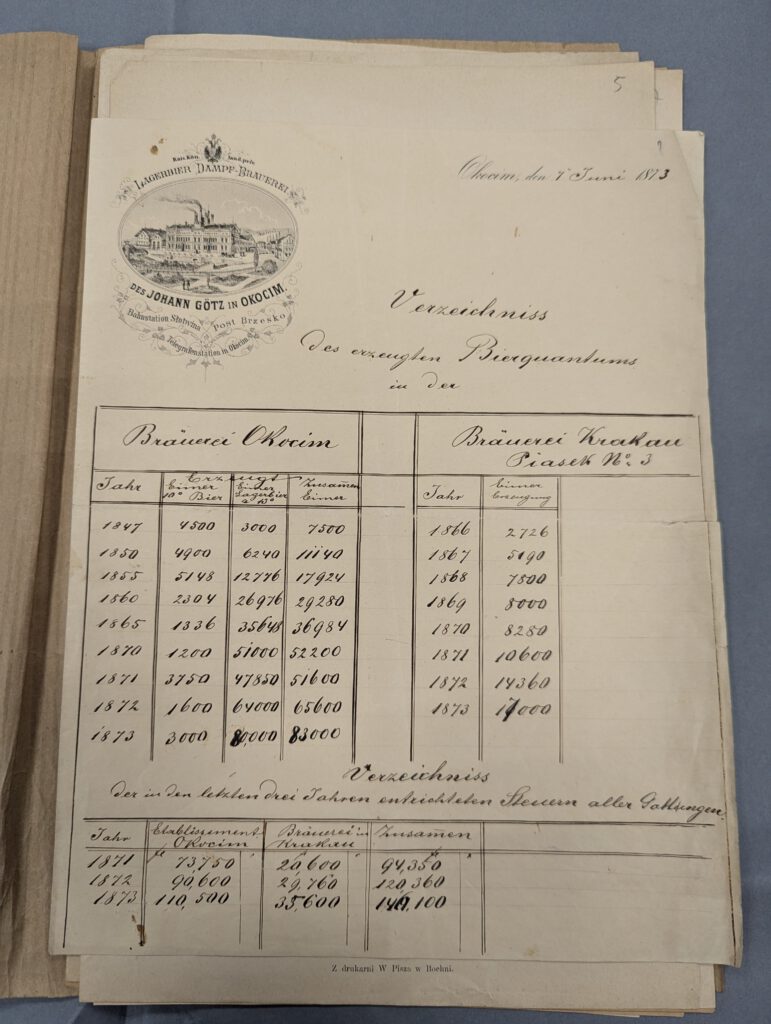

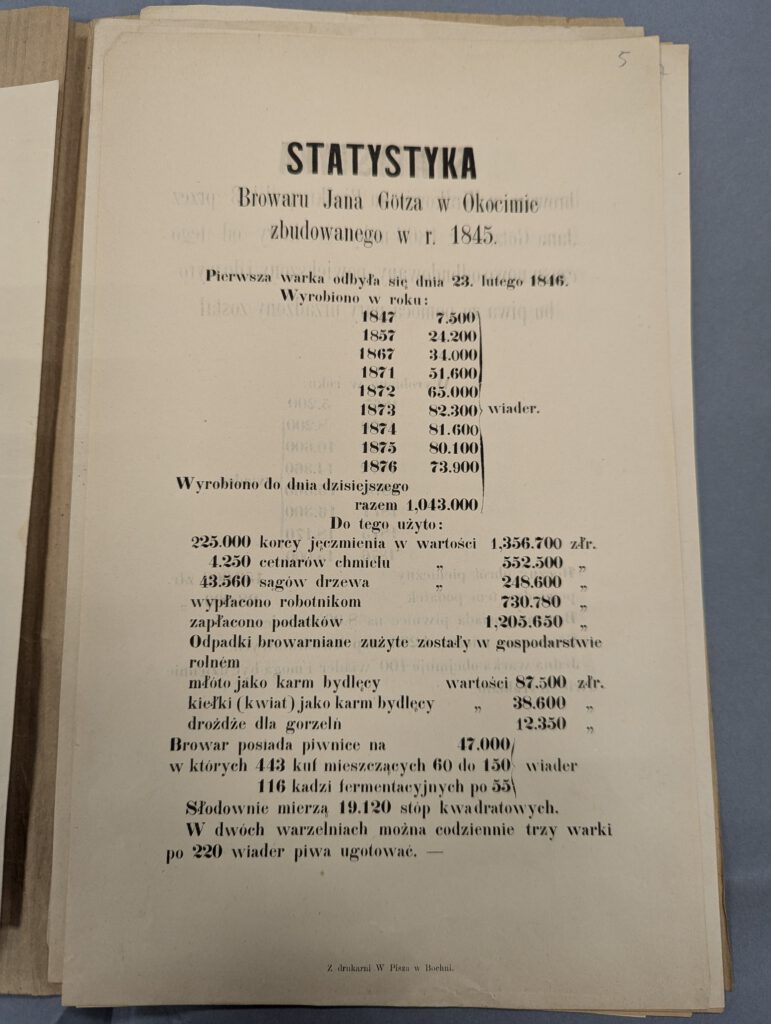

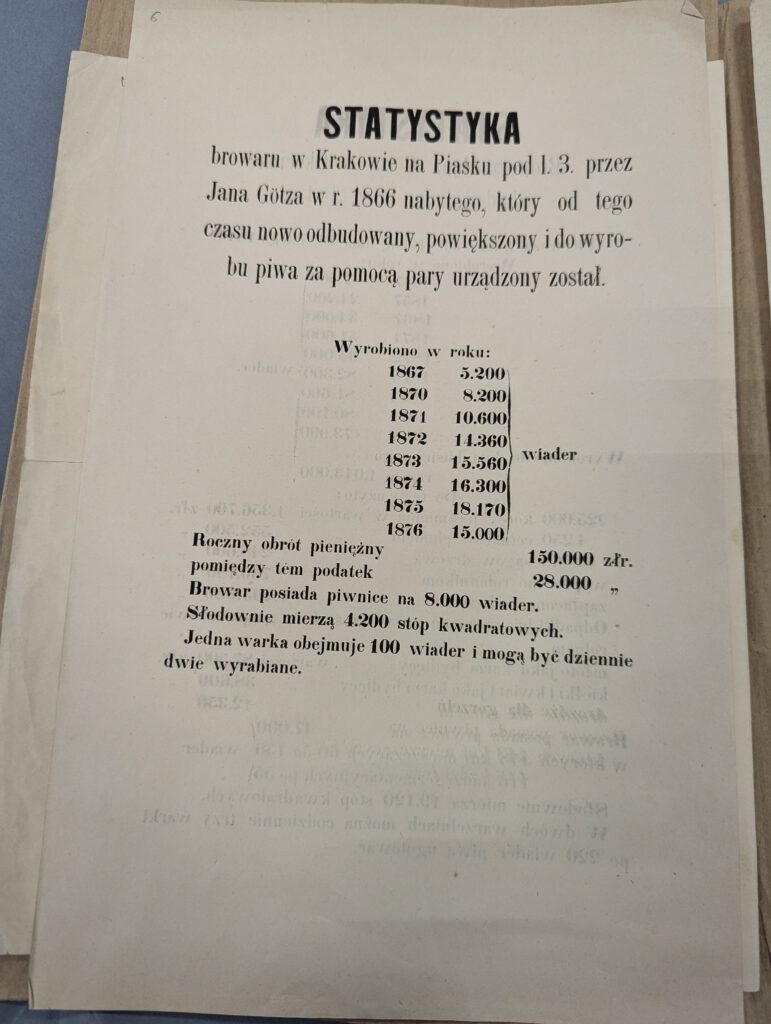

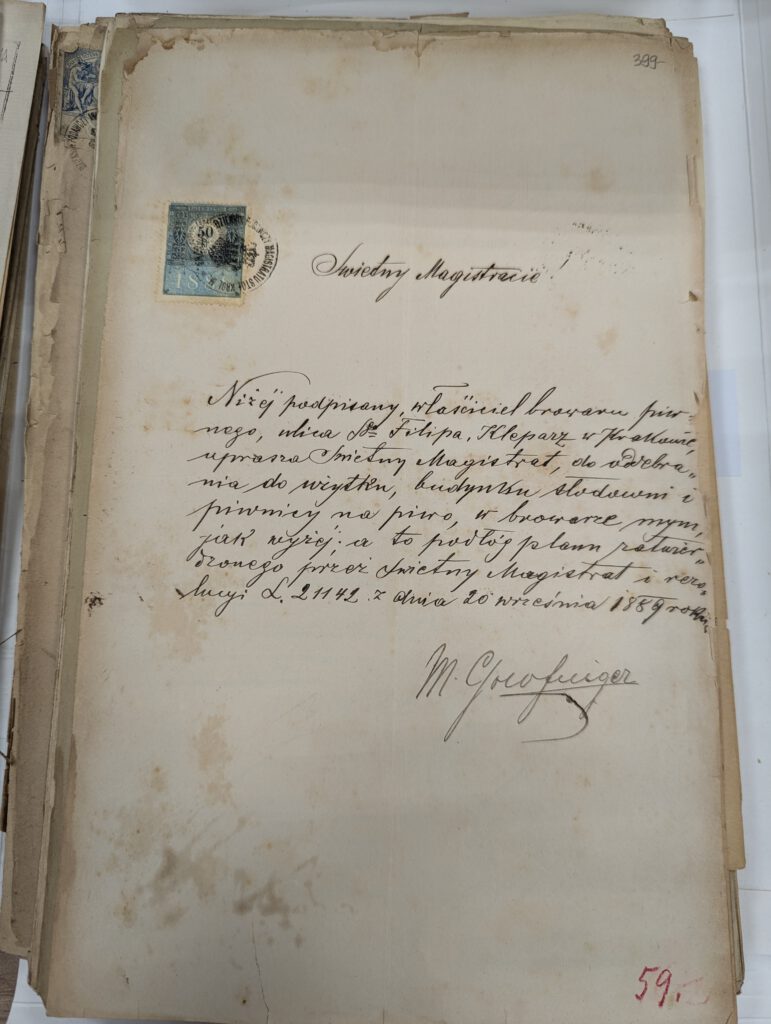

And finally, Jacobsen announced his travel plans (which he expected to be his last big journey): first he wanted to visit Johann Götz in “Oswiecim near Krakow” (he probably meant Okocim) and then travel from there to Vienna and Munich, and further on to West Germany and hopefully to Lyon and Marseille. He hoped to meet Sedlmayr in Munich, but if he didn’t meet him there, he’d try to catch him in his summer apartment to meet his “friend and master” once more.

I find this letter particularly fascinating for a few reason. First of all, it shows the great admiration Jacobsen had for Sedlmayr who considered to be his teacher from whom he learned about lager brewing and in particular about bottom-fermenting yeast, and how much he thought he owed Sedlmayr for his own success.

Second, it shows how durable repitching the same lager yeast was: as Jacobsen himself said, he never needed to change his brewery’s yeast, which he had gotten from Sedlmayr himself, in 37 years of brewery operation. He also knew that changing yeast, even though it was done, indeed used to be a relatively rare thing. That way, this new pure yeast was exactly the innovation the brewing industry needed, as more and more breweries were brewing beer all year long, and sooner or later other breweries also would have run into the problem of wild yeast contamination in their own pitching yeast. In retrospect, we now know how incredibly successful Hansen’s method of isolating single cells and growing pure pitching yeast really was, as the method was widely adopted by the brewing industry within just a few years.

Nowadays, only very few breweries repitch their house yeast without having purified it. Among lager breweries, all pitching yeast is grown from pure yeast strains, and having a choice in pure strains has become a commodity not just in the industry, but even for home-brewers.

And finally, we learn about the fermentation properties of the yeast itself, which is pretty close to what you’d expect from a bottom-fermenting yeast during the 19th century: relatively quick fermentation (just 10 days) at temperatures of at most 8°C, with a relatively poor apparent attenuation of 50-55%. At least in other beers of that time period, the attenuation only slowly improved during the lager period where the specific gravity dropped to 4 to 5°P and helped carbonate the beer. In my book about Vienna Lager, I put up the hypothesis that becuase of these properties, the lager yeasts at the time were most likely type 1 (“Saaz-type”) bottom-fermenting yeast strains, as they were better suited to the lower fermentation temperatures in fermentation and lagering cellars that could not be finely controlled yet.

J.C. Jacobsen’s letter to Gabriel Sedlmayr dated 7th May 1884 is a great example of what was new, innovative and exciting to brewers at the time that we now consider to be a given. It also shows how closely connected the European lager brewers were back then: Jacobsen and Sedlmayr communicating by mail, Jacobsen visiting Johann Götz and various people in Vienna, Munich and France, the recognition of Weihenstephan as an important beer research lab in Bavaria, etc. They were more than practitioners, but also innovators who were not afraid to share their findings with each other, all with the purpose of bringing the whole industry forward and lifting the overall quality of beer, but also improving efficiency within the industry.