In a recent conversation I had with Michel Stenzel of Schlossbrauerei Hundisburg, the topic of Styrian hops (steirischer Hopfen) came up. I didn’t know too much other than that most of the hop growing nowadays of what used to be Styria is happening in Slovenia today, while in Austria, only a small hop growing agriculture in Leutschach has survived (or rather, was reestablished after World War 2, like Upper Austrian hop growing) with as little acreage as 80 ha (for comparison: in Hallertau, the total hop acreage amounts to 17,100 ha).

What is also well-known is that the “classic” hop variety from Slovenia is Styrian Golding, nowadays more commonly marketed as Styrian Savinjski Golding, referring to the Savinja region of Slovenia. Styrian Golding started off as cultivar of Fuggle hops getting planted in the region.

Prior to that, Styria had its own native hop variety, simply known as “Steirischer” (i.e. Styrian). In his 1930 Handbuch der Brauerei und Mälzerei, Prof. Franz Schönfeld listed Steirischer as a descendant of Saazer (žatecký poloraný červeňák) hops, together with Schwetzinger, Tettnanger, Neutomischler (Nowotomyski) and Auschaer Rothopfen (red bine hops from Uštěk). This old variety was eventually replaced with the more disease-resistant Styrian/Savinjski Golding hops, I wrote about this before.

Doing a bit more research (basically just checking old newspapers for mentions of Styrian hops), I came across something interesting: Styrian hops weren’t particularly well known in the 1850s and 1860s. Nevertheless, the hops found buyers: in October 1858, a Graz newspaper reported something previously unheard: bales of local Styrian hops getting sent by train to Bohemia, the #1 hop growing region of the Austrian Empire at the time. In the middle of the 19th century, Styrian hops still had a major reputation issue: the quality was fine, and price-wise Styrian hops sold at roughly the same price as Auschaer hops, but once buyers knew they were Styrian hops, they weren’t interested anymore, even when they were packed in Saaz bags.

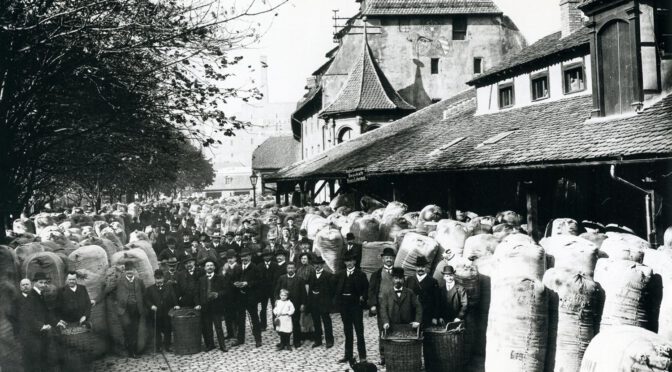

That last bit got me interested. Styrian hops in Saaz bags? Yes, that was a thing, apparently. In 1866, Bohemian hop traders came to Styria, bought over 800 bales of hops while outbidding local buyers, repackaged them into Saaz bags they had brought themselves, and shipped the hops back to Bohemia. Quality-wise, the hops were absolutely comparable with Saaz hops, except you needed 40% more hops (7 Pfund instead of 5 for a 40 Eimer batch of beer), indicating a lower alpha acid content.

Once Styrian hops were sold under their own name, they actually fared really well. This happened first in 1875, and the German Hop Association considered it to be the best hop variety right behind Saaz city hops (meaning the Saaz hops were grown on city ground and not somewhere in the surrounding district). Besides its fine qualities, it also went to market earlier than other hop varieties, which was a great advantage and got Styrian hop farmers to achieve some of the highest prices.

The virtual equality of Saaz hops and Styrian hops also shows in 1877 pricing, where Saazer, Spalter and Styrian hops all sold for the same price, though in that year, neither of these varieties were the most expensive ones.

Still, the fact that Bohemian hop traders would repackage Styrian hops and sell it as Saazer hops seems like a dubious business practice. They probably did it because they knew that the quality was perfectly fine, that customers would not be able to smell or taste the difference, but they basically arbitraged by misrepresenting the origin of the hops. Due to the poor (but unwarranted) reputation of Styrian hops, this misrepresentation was material to the price that could be charged for them. In my book, that’s fraud.

Interestingly, this is not even the first time I came across accusations of fraudulent misrepresentation of hops. In his 1818 book Das Bamberger Bier, Johann Seifert claimed that he had witnessed how hops had been bought in Amberg (east of Nuremberg), brought over the border into Bohemia, and then reimported into Bavaria with a Bohemian hop seal on the bales. He was very critical of a supposed superiority of Bohemian hops, and tried to get brewers to use cheaper local hops of the same quality instead of potentially getting defrauded with “Bohemian” hops that were actually grown near Nuremberg.