When brewers measure the specific gravity of their wort or their finished beer, the two most common scales to use are either specific gravity (SG) which is particularly common in the UK and the US, and Plato which has found its way into the standard methods of beer analysis in Europe and much of the rest of the world.

John Richardson was the first one to come up with a method to measure extract in the late 18th century, and his measure of how many pounds per barrel wort was heavier than water found widespread use through devices like Long’s saccharometer.

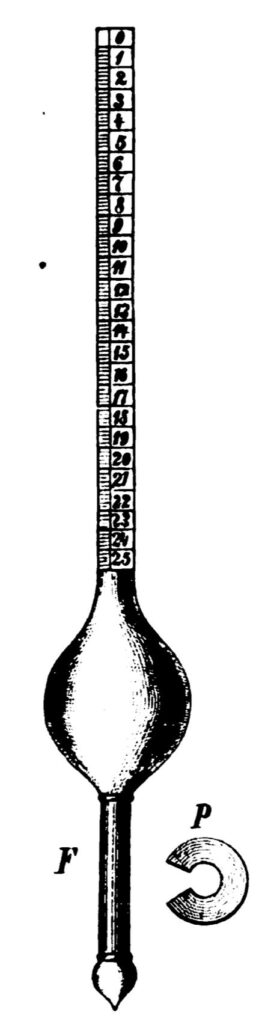

When I recently went through Philipp Heiß’s “Die Bierbrauerei mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Dickmaisch-Brauerei” from 1853, I was surprised to see the use of 3 scales to measure extract. Philipp Heiß was the former brewmaster at Spaten brewery, and through Gabriel Sedlmayr’s journey through Great Britain, they had picked up the use of Long’s saccharometer (Spaten would continue using it up to the 1870s). Besides pounds per barrel, Heiß also listed two other measurements, Balling’s saccharometer, and one that was just called Kaiser’s Procent-Aräometer (Aräometer is another word for hydrometer). Interestingly, both the specific measurements and the calibration temperature for Balling and Kaiser were identical (14°Ré = 17.5°C), and both measured the amount of extract dissolved in terms of percentage of the overall weight. So that got me thinking: were there in fact two practically identical saccharometer systems around at the time? And why does every brewer know the Bohemian brewing scientist Karl Josef Napoleon Balling (at least by surname), and nobody Bavarian chemist Kajetan Georg von Kaiser?

Turns out, the field of beer analysis in German-speaking countries was far from settled in the 1840s and 1850s. The first method that can be found in brewing literature of the time was Prof. Fuchs’ hallymetric method which involved measuring how much pure sodium chloride could be dissolved in a sample and subsequently how much lighter it got when vaporizing all the alcohol in it. In terms of process, it took a relatively long time and required consumable supplies.

Prof. Kaiser constructed his Procent-Aräometer around 1838, while Prof. Steinheil followed another approach through this “optical-areometric” method which we first published in 1843. It involved a beam balance and a refractometer and was praised for being easier to use than Prof. Fuchs’ method.

In an article by Prof. Holzner of Weihenstephan from 1883, it is noted that while Steinheil’s method was widely quoted in contemporary brewing literature, it seems like nobody actually understood the method as nobody caught two miscalculations in Steinheil’s original publications.

Balling started his research of fermentation chemistry in 1833 and first published about the general use of hydrometers in 1837, followed in 1843 by a paper about using a saccharometer to analyze beer and in 1844 his first book about fermentation chemistry (n.b. the link is to a later edition from 1854).

Steinheil did not seem particularly happy about Balling’s method, as he published separate articles both about his own method and about Balling’s “saccharometric beer analysis” in 1846. Reading the article gives me the impression that Steinheil either didn’t understand Balling’s method, or misrepresented it on purpose. Steinheil claims that Balling requires the vaporization of alcohol in samples, accuses the method to be imprecise compared to other methods at the time, and in general sees no advantage in Balling’s method. The article finishes with Steinheil suggesting that Balling should work on topics in which he is knowledgable, and that in the future, should he ever publish again, should be less arrogant and show more humility.

Balling did not seem to have directly replied to this attack, but rather in a short article pointed out issues both in an article published by Prof. Fuchs as well as Steinheil’s article about the optical-aerometric method. According to Balling, what they were missing was an understanding of fermentation theory, but he still pointed out that Steinheil’s scales were potentially more precise than saccharometers.

Ultimately, Balling’s method became the standard over the years, not just because it was dead easy to use, but also because Balling had developed this whole theory of fermentation/attenuation theory (he seemed to have used the German terms Vergärungslehre und Attenuationslehre interchangeably) which made it very easy to calculate alcohol content and degree of fermentation of a beer from just two quick measurements, the original extract before fermentation and the apparent extract after fermentation had finished. In Austria, Balling’s work even very quickly found its use for taxation.

Steinheil’s downfall came when he was too aggressive in pushing his own method with Bavarian officials: while his beam balance was made an official method in Bavaria to measure extract, the optical part of his method was not. To show how useful his method was, he conducted some measurements on his own and in 1846 wrote a letter to a Bavarian ministry in which he claimed that his analyses showed that the beer of the season had a lower extract than expected, thus brewers must have illegally used lower amounts of malt than they had to (at the time, Bavaria strictly regulated how much malt a brewer had to use to brew a particular volume of either summer or winter beer), which according to Steinheil showed the necessity for a simple analysis method (i.e. his own). Not only did he accuse brewers of fraud, the publication of this letter also angered local beer drinkers. To avert another beer riot like in 1844, officials in Munich had to lower the beer price. The only problem was: the barley used for brewing the 1846 beer was of poor quality, the harvest had been bad, and the malt gave lower extract than usual.

Steinheil also had his findings co-signing by Prof. Kaiser, who did not oversee parts of the calculation and was only made aware of the letter after Steinheil had sent it off. The ministry of course immediately ordered a verification of Steinheil’s result, which was negative: all beers were well within their parameters and of excellent quality.

It was decided that local authorities were to be equipped with the means to conduct such beer analyses themselves in the future. To answer the question which method was the most suitable, the polytechnic association of Bavaria put together a committee to investigate it. This committee consisted of the leading brewing chemists at the time, like Prof. Fuchs, Prof. Kaiser and Prof. Steinheil, but also brewing practitioner Gabriel Sedlmayr.

During this work, Steinheil was very insistent that his method was the best, of course with the idea that he’d be able to sell his devices to the Bavarian State, but all his attempts to have his device put first were struck down by the rest of the committee. Gabriel Sedlmayr even said that it took him over a year from being instructed in the use of Steinheil’s method to getting results with it that were verifiably correct. In later experiments, it was shown that Steinheil’s method deviated from the others, so Steinheil kept submitting further undated analysis protocols which suddenly showed the right results that matched up with other analyses. The whole conflict escalated when Steinheil made further outrageous claims about devices he had invented for Prof. Fuchs, all of which were countered by sworn statements from other members of the committee that Steinheil is not telling the truth. This seems to have further deteriorated his already questionable reputation.

From Prof. Holzner we also learn why Kaiser’s method eventually disappeared: Prof. Kaiser had sold the rights to build his Aräometer to a company named Greiner. Unfortunately, the company lost the instructions how to build the device, and so production simply ceased.

Balling’s success though meant that his calculations were put under further scrutiny: in Bavaria, Dr. Reischauer helped with its popularization, which eventually got him to re-examine Balling’s tables as he came across some deviations in his own private experiments. Balling had not published all his data, but rather only finished conversion tables, and seemed to have made some mistakes in it. Another brewing scientist named Schultze also did his own experiments to come up with another conversion table. Ultimately, Dr. Holzner was able to show that any deviations between Balling, Schultze and Steinheil (who had also created similar conversion tables) could be simply explained by reading errors.

The rest is history. Balling’s work was later refined in 1900 by Dr. Fritz Plato, who built upon Balling’s publications but calibrated it to 20°C. Balling’s formula (that puts original extract (before fermentation), real extract (after fermentation) and alcohol content in a direct relationship to each other and allows the calculation of each of these if the two other values are known) can be found in every serious brewing text book, while Steinheil’s and Kaiser’s methods have drifted into obscurity.