While researching a different topic, I recently came across an article in the Austro-Hungarian Café and Inn Newspaper (it really rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it?) that I hadn’t seen before. It basically contains general information about the size and the operation of both the breweries belonging to Anton Dreher (in particular Kleinschwechat, Steinbruch, Michelob and Trieste) and the Burghers’ Brewery in Pilsen (since 1898 and nowadays better known as Pilsner Urquell). It’s full of numbers, but because they’re from the same time period, they allow for some interesting comparisons about the extent of the businesses.

In terms of production, the largest brewery was of course Dreher Kleinschwechat, with about 610,000 hl for the brewing season 1892/1893. Pilsen on the other hand brewed 522,270 hl in the same time period. Dreher’s Hungary-based brewery in Steinbruch brewed another 400,000 hl, while for the other two Dreher breweries, no volumes are listed. It shows to what a large operation the Pilsner brewery had grown, while Dreher’s advantage was having multiple large breweries across Austria-Hungary that were all serving different markets.

As for the malting and brewing operation itself, there were some stark differences: Kleinschwechat had about 23,000 m2 in malting floors as well as 14 kilns, Steinbruch had 10,788 m2 with 7 kilns, while Trieste only operated a single kiln. Practically, most of its malt was actually produced in Kleinschwechat and shipped down to Trieste. The malting capacity of Michelob was not listed. Pilsen did well with “just” 9,000 m2 of malting floor and 10 kilns.

When it came to brewing itself, Kleinschwechat featured 3 coppers for boiling wort, 4 mash tuns, 4 coppers (mash kettles) for boiling mash, and 4 lauter tuns. The wort was cooled on a total of 29 copper coolships of a total surface area of 2,500 m2.

Steinbruch operated 8 coppers (presumably smaller ones than in Kleinschwechat) and 11 coolships of 698 m2.

Pilsen on the other hand had 5 separate brew houses: the original one with 1 copper and 1 mash tun (since no dedicated mash kettles or lauter tuns were listed, I assume the copper was used for boiling decoctions and the mash tun also functioned as lauter tun), one built in 1852 with 1 copper and 1 mash tun, then the third brew house built in 1862 and extended twice in 1872 and 1874, with a total of 6 coppers and 6 mash tuns, and then two more brew houses, built in 1888 and 1894, with 2 coppers and 2 mash tuns each. That’s a total of 12 coppers and 12 mash tuns. Cooling operations were supported by 22 iron coolships.

In the fermentation cellar, Kleinschwechat had 2,000 fermenters with a total capacity of 40,000 hl, Steinbruch 1,200 fermenters with 30,000 hl capacity, and Trieste just 210 fermenters of an average size of 30 hl, adding up to 6,300 hl. Pilsen operated 2,000 fermenters, but no volume is listed.

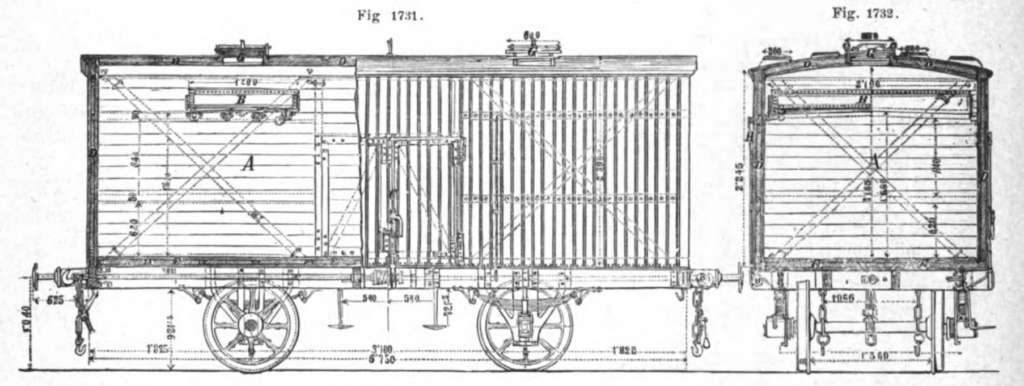

One thing though where Pilsen absolutely excelled the Dreher breweries was the number of beer wagons: while Kleinschwechat owned and operated 60 of them, and Steinbruch 20, Pilsen had much more capacity for export with a whopping 132 beer wagons. With the improved train connectivity of Pilsen since the 1860s (the article specifically cites the 1862 opening of the Bohemian Western Railway that connected Pilsen to Prague by train), it could ship its beer all over Europe and beyond.

The manufacturer of these beer wagons was F. Ringhoffer from Prague Smíchov. Thanks to the book Die Mechanische Technologie der Bierbrauerei und Malzfabrikation from 1885, we know more about these beer wagons.

The construction was double boarded, and the space between the boards was filled with a poor heat conductor as insulation material. It contained 2 ice reservoirs for up to 1,100 kg of ice that could hold the inside at a constant 4°C for 5 and half days. Melted water and condensation was drained at the bottom, using a bend to ensure that no outside air could get into the sealed wagon. That way, any freight could rest on a completely dry floor. The remaining space was sufficient to transport 25 casks of 200 liters each, i.e. each wagon could hold up to 50 hl of beer at a time. This was only slightly less than the ice wagons used by Dreher, which had a capacity of 54 hl and could keep its load cool at 4°C for up to 7 days.

In terms of refrigeration at the respective breweries, all of them used Linde refrigerators. Linde had actually been contracted to develop an artificial refrigeration machine for Dreher’s Trieste brewery, and while development was done by Linde at Spaten brewery in Munich, the first Linde refrigerator was officially sold to Dreher in Trieste. In 1894, the Trieste brewery was operating two of them, while Kleinschwechat had 8 Linde refrigerators “Nr. VI” (presumably a newer model), and Steinbruch operated 6 of them. According to the article, Pilsen only operated a single Linde refrigerator, but it’s unclear which specific model.

Interestingly, the refrigeration machine the brewery in Pilsen was using had been built under license from Linde by E. Škoda, the Pilsen-based mechnical engineering company, probably best known through the Škoda car brand and the Škoda trams in Prague.

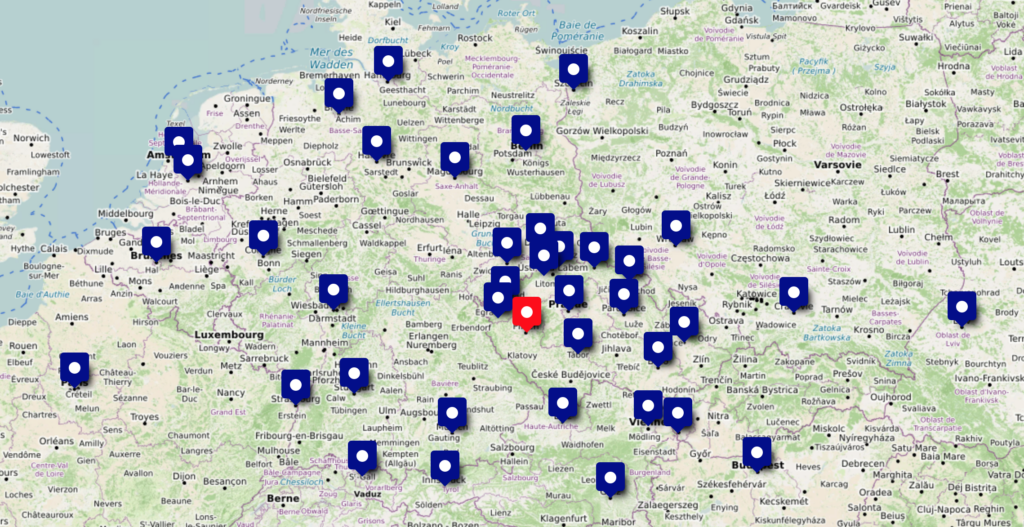

The article also lists all the distribution centers in Austria-Hungary, Germany and the rest of Europe plus one importer in New York City, which I turned into a map to get a better feeling about how widespread their beer was.

In addition to all these statistics I listed above, we also learn more details about the Burghers’ Brewery Pilsen. As you’re probably aware, the brewery was founded by the citizens of Pilsen with brewing rights in 1839. The article specifically says that it was 250 houses with brewing rights, and their duty was to elect a new administrative committee every 3 years.

We also get more insight into the beer types that were brewed at the time: as was still usual at the time, two types were produced, an 11% Schankbier (the percentage refers to the original gravity, not the ABV) that still needed 2-3 weeks of lagering before it was tapped and was brewed and sold only during the winter, and a 12% Lagerbier that was entirely free from yeast (due to the long lagering) and only sold during the summer season.

The article also discusses the modest beginnings of the brewery itself: the first brew only had a volume of 64 Eimer (3621 liter), and the total volume of the first brewing season was a mere 3657 hl. In 1843, Pilsen had a population of 8,892, that’s just a bit more than 41 liters per capita. Could it be that the amount of beer produced by the Burghers’ Brewery was initially not nearly enough to cover the demand of consumers?

In any case, the business grew so well over the years that Burghers’ Brewery Pilsen grew to a size similar to Dreher’s Kleinschwechat brewery. While the production volume was still smaller in 1894, it seems like the Pilsen brewery was prepared much better for export across Europe. By 1912, Pilsner Urquell produced almost 1 million hl of beer per year and was considered to be Austria’s largest brewery, while Dreher Kleinschwechat was “only” producing 594,865 hl in 1912 and about 621,398 hl in 1913.

If you want to learn more about Vienna Lager and the history of Dreher’s breweries in Kleinschwechat and elsewhere, you can find more about the topic in my book Vienna Lager.