At HBCon 2024 (more about the event here), one of the sessions I attended was a seminar about how to brew easy-drinking Bockbier. Basically, brewmaster Stefan Zehendner told us all the details about the beer, the idea an concept behind, everything about the ingredients and the brewing process, and of course lots of little details and anecdotes.

A lot of information about that particular beer can already be found in this article in Craft Beer & Brewing, and if you’re a subscriber to that magazine, there’s even a home-brew recipe available.

Mönchsambacher produces a total of about 6000 hl of beer per year, with no intention of further growing the business. Of this, about 1,500 crates (i.e. 150 hl) is Weihnachts-Bock, which is usually sold out within a week.

The Weihnachts-Bock has about 17.5 to 18 °P original gravity. To achieve consistency, all the lager tanks are blended into one beer during packaging. It has about 3.3 to 3.5 °P residual extract, and is hopped to 48 IBU. Compared to the brewery’s other beers, this CO2 content is slightly higher, making this whole beer a hop-forward, not too sweet, well-integrated beer.

The brewmaster considers his brewing water to be one of the keys to his beer. The water is very hard: 28 °dH (German degrees of hardness), where 1° equals 0.1783 mmol/l. About 13 to 14 °dH are magnesium, and about the same amount is calcium, much of it bound to sulfate. This hardness results in a higher mash pH for the Bock, around 5.6 to 5.7.

The grist is simple: 100% Pilsner malt. As many other local breweries, Mönchsambacher gets their malt from local maltings Bamberger Malz. The grist is also used for all the other bottom-fermented beers, except for the Festbier, which is brewed from a 50/50 blend of Pilsner and Vienna malt. The Pilsner malt from Bamberger Malz is slightly less modified.

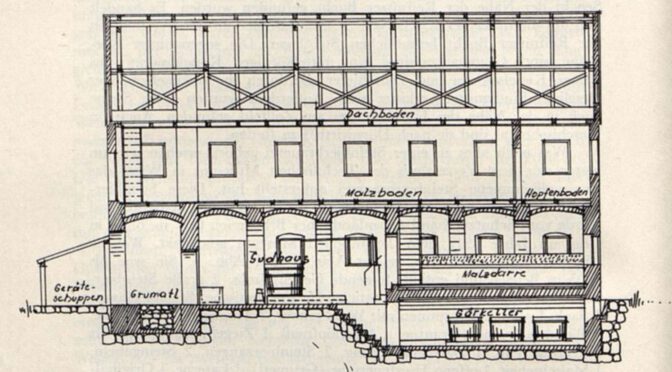

This is what the mash schedule looks like:

The grist is mashed in at 45°C, then rested for 10 minutes.

Then the mash is heated up to 52°C, for another 10 minute rest.

After this rest, the mash is heated up to 62°C, and the first (and only) decoction is pulled: about one third of the mash volume (relatively thin mash) is pumped into the kettle, brought up to 72°C and rested for 15 minutes for saccharification. It is then brought to a boil and boiled for 5 minutes before it is mixed back.

Stefan called this decoction to be important for the bright golden colour of the beer and a more robust (he used the word kernig which is impossible for me to translate) body.

After mixing the decoction back, the mash should have reached 72°C. It is then left to saccharify for another 20 minutes, after which it is heated up to 78°C, which is when lautering starts.

The wort is boiled for a total of 75 minutes. The only hop variety used in the brewery is Perle. In the case of the Weihnachts-Bock, the hops are added at 3 points: at the beginning of the boil, 25 minutes before the end of the boil, and in the whirlpool. The hops in the whirlpool are added beforehand, so it has 10 minutes of contact while the wort is pumped into the whirlpool, and then left for a trub cone to form for another 15 minutes until the wort is pumped out of the whirlpool.

The wort is then chilled to 7.5°C, yeast is pitched, and fermentation happens at 9.2°C. The brewmaster said the yeast strain they use is W-34/72 which they get delivered from Speckner yeast lab in Augsburg. I’ve not been able to find that particular strain in Speckner’s list of available strain, so this is probably a matter of miscommunication (Speckner has W-34/70 and W-34/78 in their portfolio). In any case, Zehendner finds the water much more important than the yeast, so for home-brewers, W-34/70 is probably totally sufficient.

What is important though is that the yeast must have gotten used to the brewery before it is used for fermenting the Weihnachts-Bock. So any yeast going into Weihnachts-Bock has been pitched once or twice before.

Fermentation takes 13 days in tanks which are left open, so it is effectively open fermentation. Before moving the beer into lagering tanks, Kräusen (freshly fermenting beer) from another tank is added at about 10% before it is lagered to ensure a very clean secondary fermentation/lagering. Lagering itself happens at 2°C for a total of 12 weeks, with fermentation slowly progressing for 10 weeks.

The last time this recipe has changed was when the brewery upgraded their brew system in 2000. As part of the adjustments, the number of decoctions was reduced from 2 to 1, and because they had sold the coolship, the hop addition had to be removed. Because there was no more coolship, the whirlpool was instead chosen to have a similar geometry so that the wort can “stink out” in the same way, so basically that DMS and other unwanted chemical compounds can evaporate in the same way and at the same rate.

When the beer is bottled, it is always unfiltered. Zehendner considers a bit of yeast to be absolutely vital to have a beer that can age well. Apparently, the beer will ferment a little bit more after bottling, so practically, the Weihnachts-Bock is a bottle-conditioned beer. The best before date is 3 months for the Weihnachts-Bock and just 5 weeks for the regular Lager. The main reason for the short date is that the beer changes in the bottle, and slowly loses its sulphur notes, making it taste different from what regular drinkers expect. Mönchsambacher also keeps their bottled beers chilled at all times, and are selling it chilled directly from the brewery.

Something that I had never heard before was the anecdote of a pediococcus infection they struggled with for about a year. Pediococcus is a bacteria that makes beer go “ropey”, it gives it a slimey texture and leaves behind plenty of diacetyl. They struggled with such an infection on and off for about a year, until they finally discovered the unlikely source of the infection: the water source! After spending about €80,000 on a membrane filter, this has finally been cleaned up and now the brewery is infection-free again. The brewmaster pointed out that the water treatment with chlorine dioxide would have been another option, but he decided against it specifically because he thinks that it could also negatively affect yeast health in the long run.

Still, this is the only time where I’ve heard that the infection vector of a brewery was the water. It is quite insidious: after disinfecting the whole brewery, all it needs is some water to rinse off disinfectants, and you got the infection back on your equipment.

Stefan Zehendner is not just a traditional Franconian brewer, he also likes to experiment: recently, they filled a batch of Weihnachts-Bock into a wine cask that was previously filled with spontaneously fermented Silvaner wine. In the future, he’s also thinking about producing Weihnachts-Bock wort and getting it fermented somewhere else as a sour beer, which also sounds absolutely intriguing. And apparently if you visit the brewery taproom at the right times, there’s a chance that a keg of Cantillon might be on, about the last beer you’d expect in Franconia.

The process I described here does not just apply to the Weihnachts-Bock, but their other Bock, the Maibock, is also brewed essentially the same way. The only differences are a slightly reduced original gravity of 16.5°P and a reduced bitterness of about 40 IBU.

And that’s how you brew Mönchsambacher Weihnachts-Bock, based on all my notes from the session at Heimbrau Convention 2024. I think this description is complete enough to brew a pretty faithful clone at home.