The German Brewing Tax Law of 1906, which went into effect on June 3, 1906, regulated the permissible ingredients for bottom- and top-fermented beers within the Northern German Brewing Tax Association. From that point onwards, bottom-fermented beers could only be brewed from barley malt, hops, water and yeast, while top-fermented beers could also be brewed using malt made from other grains, various sugars (beer sugar, cane sugar, invert sugar, starch sugar, caramel colouring) and sweeteners (for low-ABV beers only). But before that, beer tax laws in North Germany were much lenient (Bavarians hated that), and ingredients like rice could be used.

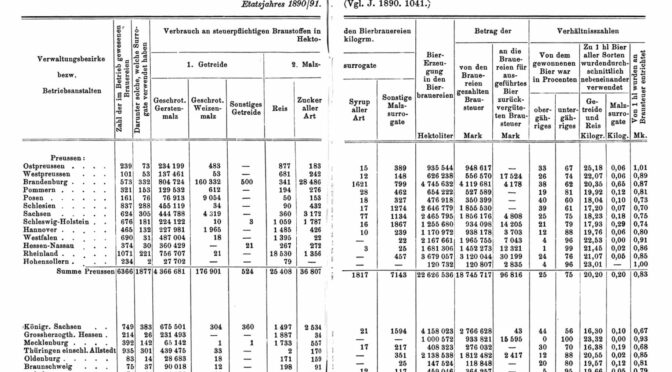

I recently came across statistics for the tax year 1890/1891 that give greater insight into that. Previously, I also wrote about bottom- vs top-fermenting breweries in Germany resp. Prussia in 1889/1890. But this goes even more into detail.

I won’t reproduce all the numbers here as that would be too much. But let’s look at some of the highlights:

An average beer brewed in the Northern German Brewing Tax Association in 1890/1891 would have been (by weight of ingredients):

- 95.75% barley malt

- 2.78% wheat malt

- 0.01% other grains

- 0.51% rice

- 0.73% sugar

- 0.03% syrup

- 0.19% other malt surrogates

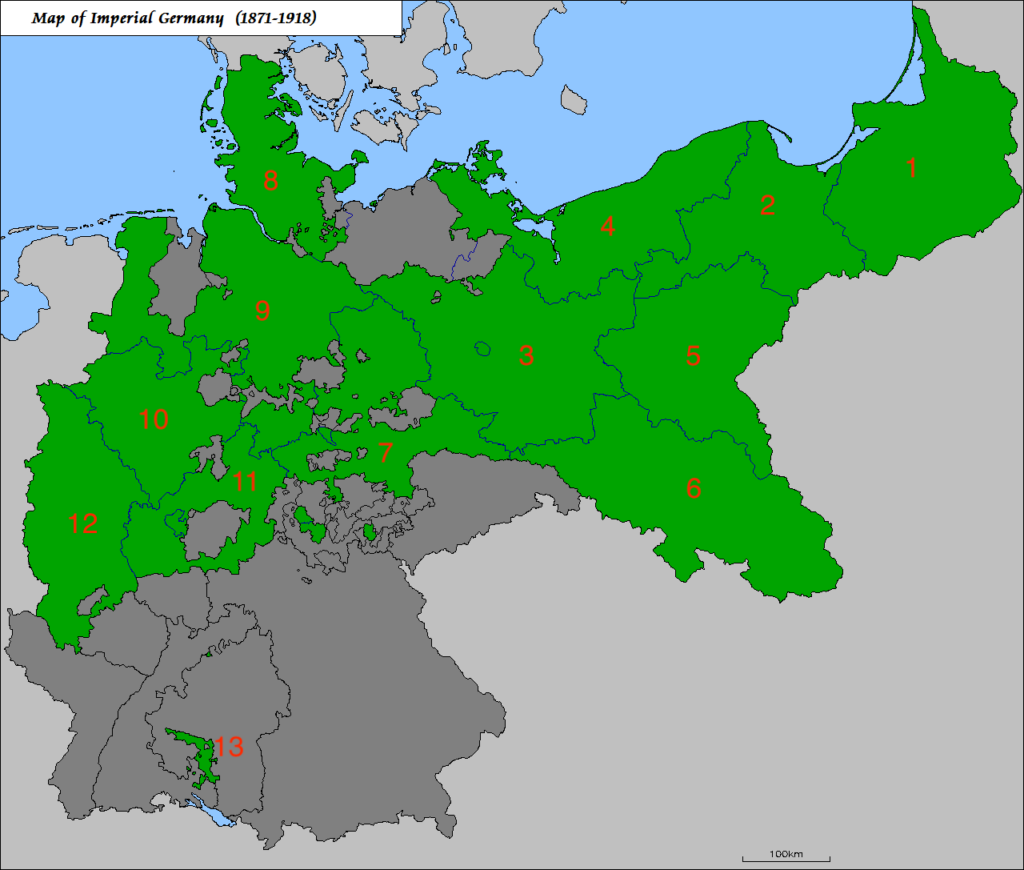

The most rice was was used in Bremen (the statistics don’t include 3 export breweries) with 3.23% rice, Mecklenburg with 2.56%, and the Rhineland, with 2.38% of all ingredients used in brewing.

When it comes to brewing sugar, Brandenburg stands out with 2.85% of the total brewing ingredients by weight. They also similarly stand out for the use of wheat malt, with 16.08%. That’s probably an artifact of the Berliner Weisse brewing industry (Berlin was part of Brandenburg) which used plenty of wheat malt. The Province of Posen was number two, with 10.46%, which absolutely makes sense: the city of Grätz/Grodzisk Wielkopolski is located in that historic Prussian province, and is best known for the Grodziskie beer style which is brewed from 100% smoked wheat malt.

It’s also interesting to see what percentage of breweries even used malt surrogates of any kind (including rice, sugar, etc.) in the first place: 83.33% in Bremen, 80.65% in Lübeck, 75% in Hamburg, and 59.46% in Anhalt. On the other end, where malt surrogates were used the least, are these places: Hohenzollern (0.85%, just 2 out of 234 breweries), Westphalia (4.49%), Province of Hesse-Nassau (8.02%) and Grand Duchy of Hesse (12.15%).

In the same statistics, we also get more insight into the distribution of top- vs bottom-fermenting brewing: the top places for bottom fermentation (in terms of production volume) in Northern Germany in 1890/1891 were:

- Grand Duchy of Hesse, 100% bottom fermentation

- Province of Hesse-Nassau, 99% bottom fermentation

- Westphalia, 96% bottom fermentation

- Brunswick, 95% bottom fermentation

Conversely, the top places where top fermentation still held on were:

- Kingdom of Saxony, 44% top fermentation

- Province of Posen, 40% top fermentation

- Silesia, 39% top fermentation

- Brandenburg, 38% top fermentation