In the reconstruction of everything related to historic Vienna Lager, there is one piece missing that I’ve not been able to conclusively reconstruct so far: its water profile, and in particular, the water profile at Kleinschwechater Brauerei, where Anton Dreher first brewed Vienna Lager.

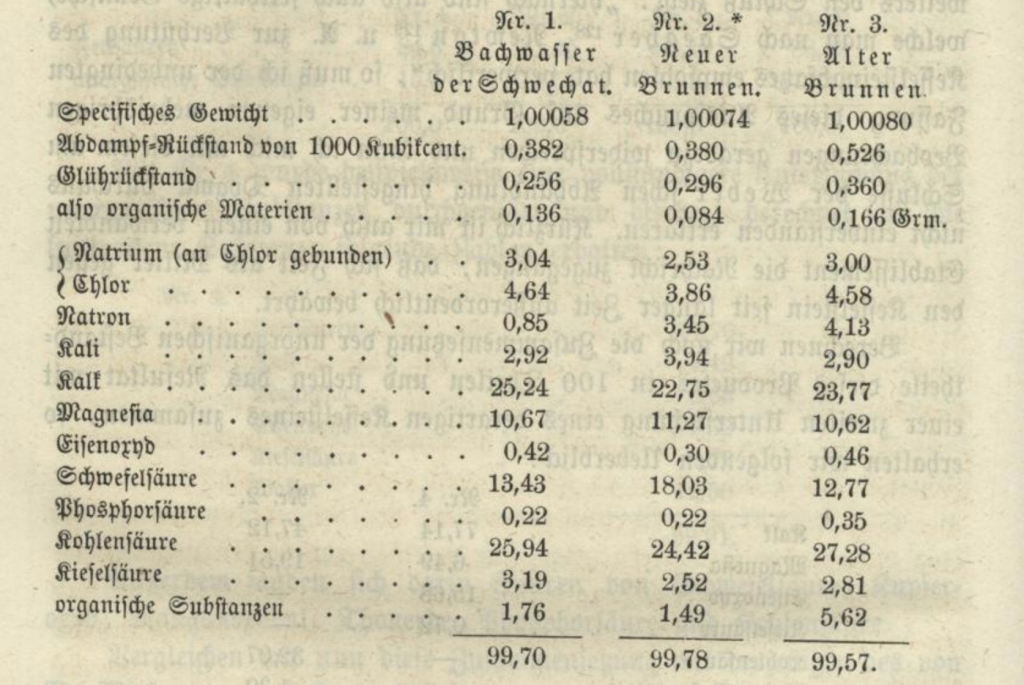

People who read my book on the subject are probably already aware of this, but for those who are not, a quick recap of the water situation there: the original Kleinschwechater brewery was located next to Kleinschwechat’s cemetery. The cemetery was on Löss soil (wind-blown silt sediment), while the brewery’s wells were dug into soil consisting of alluvial resp. diluvial gravel. By 1869, the brewery had four wells that had gone bad due to contamination from brewery and animal waste, so two further wells had been dug in the garden next to the brew house. Of these two wells, one’s water was used for brewing, for which we have a chemical analysis conducted in 1868 by Johann Karl Lermer. It looks like this:

- Specific gravity of water: 1.00074

- Total dissolved solids: 0.380 grams per litre (=380 mg/L)

- Ash content: 0.296 grams per litre

- Organic matter: 0.084 grams per litre

The dissolved solids were analysed and their constituents were listed in percent:

- Sodium chloride: 2.53%

- Chlorine: 3.86%

- Sodium: 3.45%

- Potassium: 3.94%

- Calcium carbonate: 22.75%

- Magnesium: 11.27%

- Iron oxide: 0.30%

- Sulfuric acid: 18.03%

- Phosphoric acid: 0.22%

- Carbon dioxide: 24.42%

- Silicic acid: 2.52%

- Organic matter: 1.49%

(please note that I think I previously misidentified the “Kalk” in the original German text as calcium oxide. It more likely means calcium carbonate, which I corrected in this list)

This is fairly detailed, but how does this get us to a modern water profile consisting of carbonate hardness, calcium, magnesium, sulfate, chloride and sodium? So here’s my attempt of trying to reconstruct that. Please be aware is that my last time I had chemistry lessons was 23 or 24 years ago. I also never thought myself to be a particularly good chemistry student.

I started off with the individual weight of each of the chemical compounds: 380 mg/L is equal to 380 ppm. Applying the percentage to the 380 ppm of should give us the respective ppm of each compound. Please note that I only listed the ones relevant for our water profile:

- Sodium chloride (NaCl): 9.6 ppm

- Chlorine: 14.7 ppm

- Sodium: 13.1 ppm

- Calcium carbonate (CaCO3): 86.4 ppm

- Magnesium: 42.8 ppm

- Sulfuric acid (H2SO4): 68.5 ppm

- Carbon dioxide (CO2): 92.8 ppm

I then looked up the molecular formulas for each of the chemical compounds, as well as the molar masses of all the elements found in each of the compounds.

So now let’s use this data to reconstruct what we need in our water profile.

Carbonate Hardness

Carbonate hardness is basically the concentration of HCO3–(hydrogencarbonate) ions. While we do not have this one available directly, we can reconstruct the amount from the amount of CO2. The molar mass of CO2 is about 44.0088 g/mol, so adding the mass of one H and one C gets us about 61.01604 g/mol. When we apply this to the ppm of CO2 (92.8), we get an HCO3– concentration of 128.7 ppm, or 5.9 °dH (German degrees of hardness).

Calcium

For the calcium content, we need to go the other way, and look at the calcium content of the calcium carbonate. CaCO3‘s molar mass is about 100.0088 g/mol, while Ca’s molar mass is just 40.08 g/mol, so the 86.4 ppm of calcium carbonate should translate to about 34.6 ppm of calcium, or 4.8 °dH.

Magnesium

That one is easy, because it’s listed directly, with 11.27%, which translates to 42.8 ppm.

Sulfate

The sulfate ion is SO42-, so we should be able to reconstruct it from the sulfuric acid (H2SO4) content, following the same approach as with the calcium. H2SO4‘s molar mass is about 98.08 g/mol, while SO42- is about 96.06 g/mol, so the reconstructed sulfate content should be 67.1 ppm.

Chloride

Chlorides are either chlorine ions or chlorine atoms bound to molecules by a single bond. In Lermer’s analysis, we have two chemical compounds that involve chlorine atoms: chlorine, and sodium chloride. From the chlorine, we can simply assume the same ppm (14.7 ppm), while for the sodium chloride, we need to calculate its portion (5.8 ppm). When we add both, the total chloride content should be 20.5 ppm.

Sodium

Similar to the chlorides, we have two chemical compounds that involve sodium atoms: straight up sodium, as sodium chloride. Following the same approach, we can take the ppm of sodium (13.1 pm) and add the sodium portion from the sodium chloride (3.8 ppm). This means we end up at 16.9 ppm sodium content.

The final water profile

With all this, we end up with this water profile:

- Carbonate hardness: 128.7 ppm, or 5.9 °dH

- Calcium: 34.6 ppm, or 4.8 °dH

- Magnesium: 42.8 ppm, or 9.9 °dH

- Sulfate: 67.1 ppm

- Chloride: 20.5 ppm

- Sodium: 16.9 ppm

My question to all you people out there with a better knowledge of basic chemistry than me: does this make sense? Provided the German terms for the individual chemical compounds that I translated to English mean exactly what I think they mean, does it make sense to derive the amounts of ions in the water from the amount of molecular compounds determined in that chemical analysis?

Please let me know in the comments whether this attempt of reconstructing the historic water profile of Vienna Lager at Kleinschwechater brewery (at least as analysed in 1868) makes sense or not.

(thanks to Ben for proofreading the article before I published it)