This is the second part in my series about some of the excellent lager beer that I had on our trip to the US in June 2024.

Goldfinger Brewing Company (Downers Grove, IL): History and Community

I had first been in touch with Tom Beckmann, the founder and brewer of Goldfinger Brewing Company, a few years ago, when they had first launched Danube Swabian, their interpretation of a historic Vienna Lager based on specs from my book about the beer style. I found that truly honouring, not just that somebody makes product decisions and takes a certain business risk based on things I like to write in my free time, but the extent to which Tom implemented it was better than I could have ever hoped.

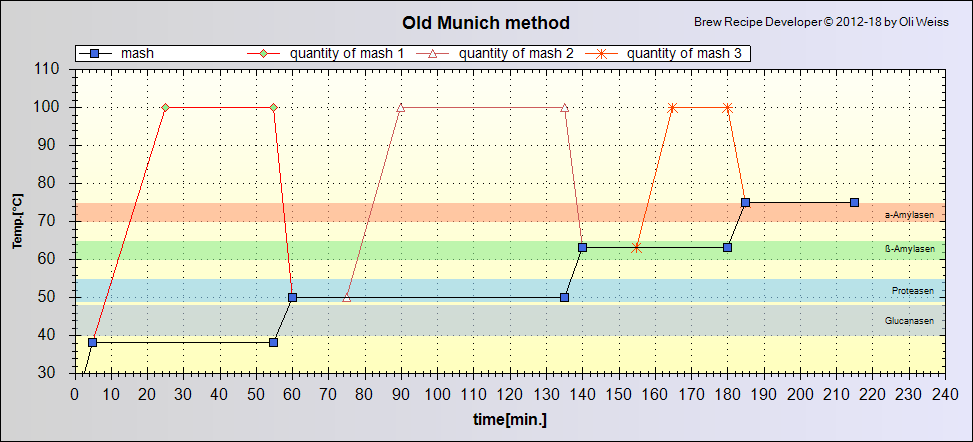

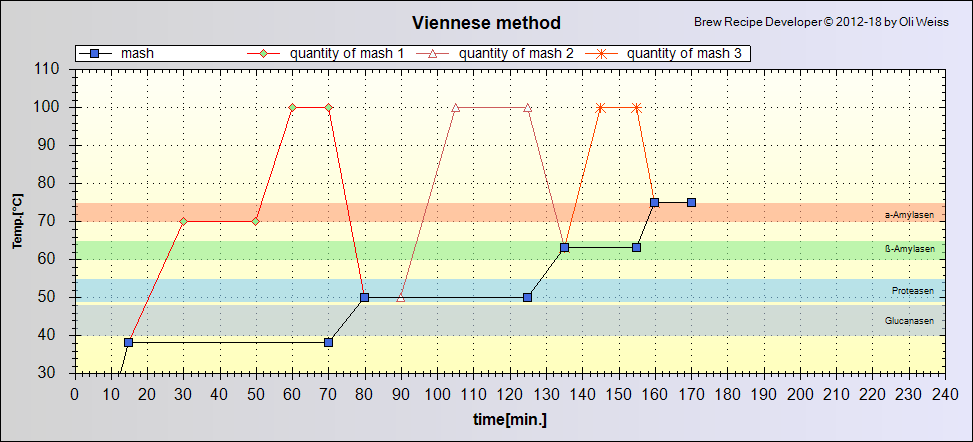

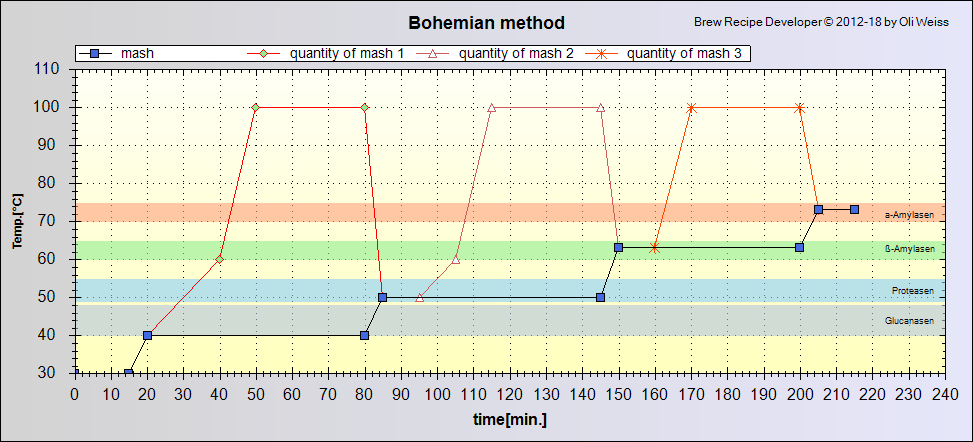

Tom is a big proponent of decoction mashing, so that was of course an element of this beer, but I think what influenced the character of the beer even more was the decision to recreate a historic Vienna malt, in cooperation with Sugar Creek Malt in Lebanon, Indiana. Using Haná barley grown in Indiana and the description from my book of how Vienna malt used to be made historically (with some adjustments), they recreated a Vienna malt quite close to the historic original.

Downers Grove is an easy 50 minute train ride away from Chicago Union Station. Add 10 minutes of walking, and you’re at Goldfinger’s taproom. When we did our trip on a Saturday, it was quite rainy. Several people in Chicago later told me how the weather was “icky”, but I actually enjoyed that, and taking the commuter train through some of Chicago’s southwestern suburbs was surprisingly relaxing.

Tom had mentioned that he was at a “brewery of the month” event in a local market hall and that he was going to join us later, so we just sat down in the busy taproom and ordered beers. Goldfinger Original (a Helles) for Louise, their regular Vienna Lager (of course!) for me.

With a very recent impression of Dovetail’s excellent beers, these two were quite different. Well, as different as beers of the same respective styles could be. What I very much noticed about the Vienna Lager was a slight residual malt sweetness, and I was somehow immediately transported back to Czechia, but was also reminded of the historic example I had brewed years ago myself.

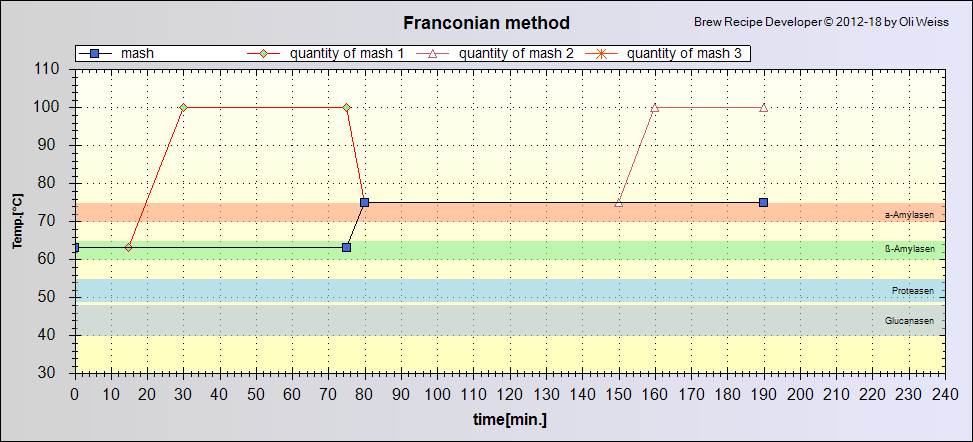

Yes, if Dovetail’s Vienna Lager is Franconian in its character, then Goldfinger’s Vienna Lager is very much Czech in the best way possible. This is not a judgment of relative quality, in my book both are equally excellent and without exaggeration some of the best Vienna Lagers I’ve ever had.

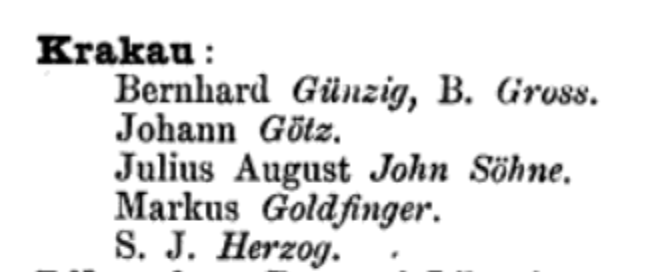

The beer was so good, I tried not to down it too quickly. Eventually, Tom arrived, and we got chatting, first and foremost about his brewery, his family history (Goldfinger brewery is named after Markus Goldfinger, a brewer and brewing equipment manufacturer from Kraków in modern-day Poland, and an ancestor of Tom), and of course about his beers.

Oh, yes, the beers: I tried all of them on the menu. I don’t remember all the details of all of them, but a lasting impression for me was that every single one of them was absolutely flawless, full of flavour, and so enticing that you would have wanted a second one of every single one of them. Goldfinger Original, Vienna Lager, German Pils, Mexican Lager, Heller Bock (it was the end of Maibock season, after all) and Hefeweizen were on tap, and all of them excellent examples of their respective styles. Not just excellent, but formulated and brewed to absolute precision.

Specifically for the German Pils, Tom told us that he was inspired by Tegernseer Pils when he spent time in Bavaria as part of his brewing education at World Brewing Academy (a cooperation of Siebel in Chicago and Doemens just outside of Munich). While it wasn’t an identical clone, I absolutely got the similarity. Bavarian Pils, whether it’s from Schönramer, Augustiner, Tegernseer or Hofbräuhaus Traunstein, is the best Pils in Germany in my book, and Goldfinger’s German Pils plays in the same league with its fine hop aroma and incredible drinkability.

Of course, no visit to a brewery is complete without a tour around the brewery facilities themselves.

You could tell by the size of everything that Tom has big plans for Goldfinger, and fortunately still lots of space to expand to.

While showing us around, he told us about some of the approaches he takes when it comes to ingredients. What I found interesting is that he uses domestic base malts from large producers such as Rahr, then local craft malts from Sugar Creek, and imported malts from e.g. Weyermann, and blends them as he sees fit.

We got to try a sample of Sugar Creek Pilsner malt, it was the most complex tasting Pilsner malt I’ve ever come across. Tom was really pleased with the malt, and I can totally understand why. In fact, I’d love to brew with malt like that myself.

Another peculiarity is that Tom is strictly sticking to lager brewing only, so only bottom-fermenting yeast will enter his brewery. You may have noticed earlier that I did drink a Hefeweizen. It was actually a collaboration with nearby Skeleton Key Brewery, where it was also produced (in my opinion, it was as good as some of the better Bavarian versions; in fact, it reminded me of Schneider Helle Weisse).

Similarly with another seasonal beer that I think has been released only a few weeks ago, the New Zealand Lager: when we told him that the first New Zealand Pilsner brewed at Emerson’s in Dunedin was actually just fermented with US-05 (a top-fermenting American ale yeast strain) at cool temperatures, Tom insisted that he’d only ever brew the style as a bottom-fermented beer.

To be completely honest, I can’t exactly remember whether we tried the NZ Lager from the tank because we tried so many beers that afternoon, but what we most definitely sampled was the Märzen and the Summer Beer. The Summer Beer was also released recently, and was inspired by Anchor Summer Beer. It’s not a clone, but Tom was apparently so impressed by the original, he took all the elements he liked so much about it and recreated them in this summerly 4.0% ABV beer.

The Märzen on the other is a completely different beast, at (IIRC) just over 6% ABV. It’s amber-coloured and has the right amount of malt flavour to make it taste distinctly like the style it’s supposed to be. I also remember a slight residual sweetness, but the beer itself was the opposite of cloying. I could see myself leisurely drinking a few Maß of that beer over the course of a long afternoon in a beer garden or a beer tent. And there was just something about it that very much reminded me of Ayinger’s Festbier of which I once had an unfiltered sample from the lagering tank.

(when you have an Austrian go to a small brewery in Chicagoan suburbia, drink their beer and suddenly reminisce about all the great Bavarian beers it reminds him of, you know the brewery is doing something very right)

Lagering times are another area where Tom doesn’t compromise. No beer is rushed, and some styles are given even more time to condition and mature, like the Märzen which gets a full 6 months of lagering, much longer than what even contemporary Bavarian breweries would do.

We eventually had to catch our train back to Chicago, so just before we were about to leave, Tom surprised us with a four-pack of Danube Swabian as well as some Goldfinger merch. I had assumed that batch of beer was completely sold out and gone, but he had kept a few. What a fantastic gift!

I managed to sample the beer when we were finally back in Berlin (at the time of writing, I still have 3 cans in my beer fridge), and there is definitely something special about it. It’s ever so slightly paler than a Vienna Lager made from modern Vienna malt would typically be, but it has a complex malt aroma and flavour that decidedly makes it not a Pilsner. To me, being able to drink that beer means so much, as I never would have thought 4 or 5 years ago when I still worked on my Vienna Lager book that it could inspire people around the world to do such meticulous collaborative work and create the most faithful reproduction of a historic Vienna Lager as of now.

(for the record, Westerham Brewery in Kent is a very close second, which got Crisp Maltings to produce a Haná Vienna malt; I unfortunately never got to actually try it).

Besides the beer and the brewery itself, there were things that particularly impressed me about Goldfinger after my visit: a deep understanding of their own history, and a great sense of community.

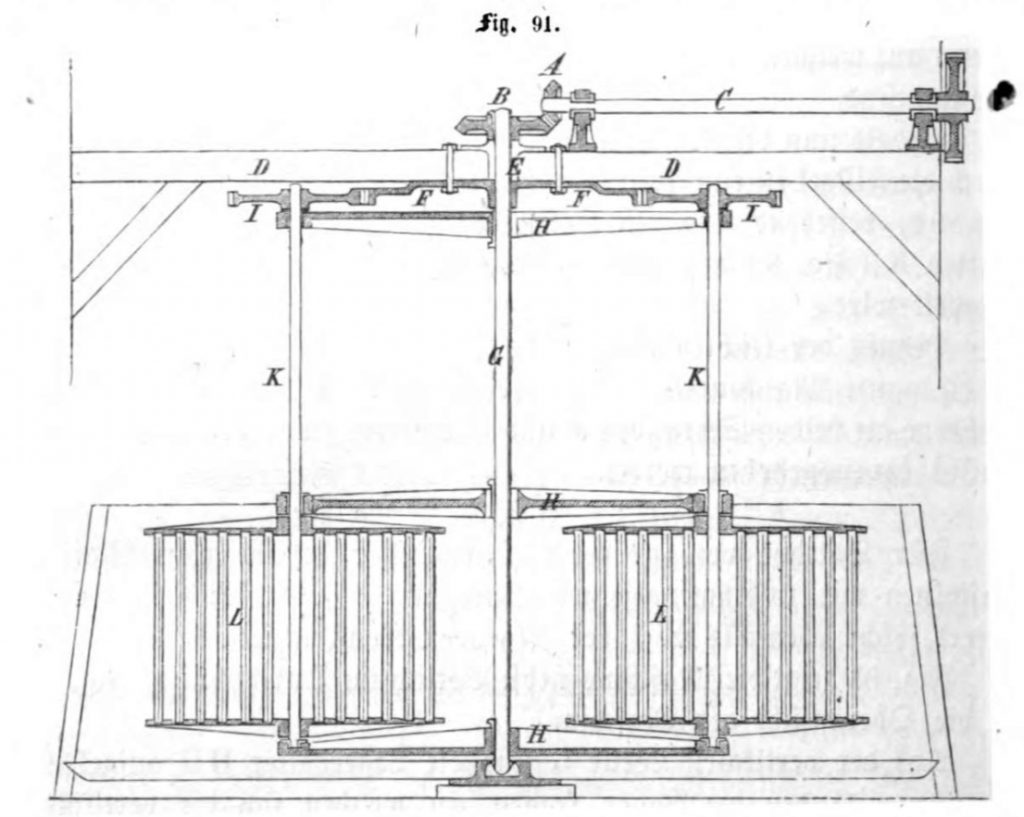

The History

While Goldfinger Brewing in Downers Grove, IL, was only founded in 2020, Tom’s family’s connection to brewing goes back to the 19th century, when his ancestor Markus Goldfinger had founded a brewery in Kraków in 1874. When you enter the brewery, the entrance area is basically a mini exhibition about Markus Goldfinger and his brewery and brewing equipment business. Tom even owns a historic Goldfinger-branded tap from the time period.

The close connection to this history absolutely resonated with me. Naturally, I was interested in how much I was able to find out about Markus Goldfinger myself. And it turns out, a few things:

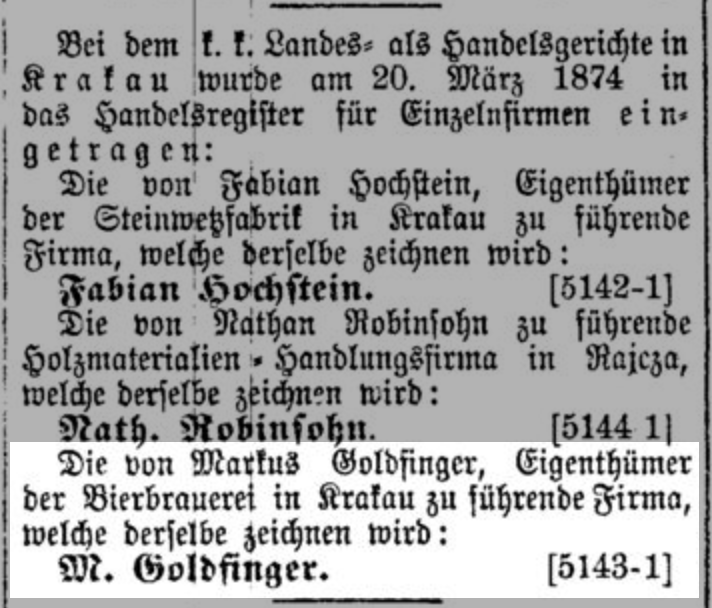

Markus Goldfinger officially registered the firm “M. Goldfinger” on March 20, 1874 at the company register at the Imperial-Royal Regional Court in Kraków (source).

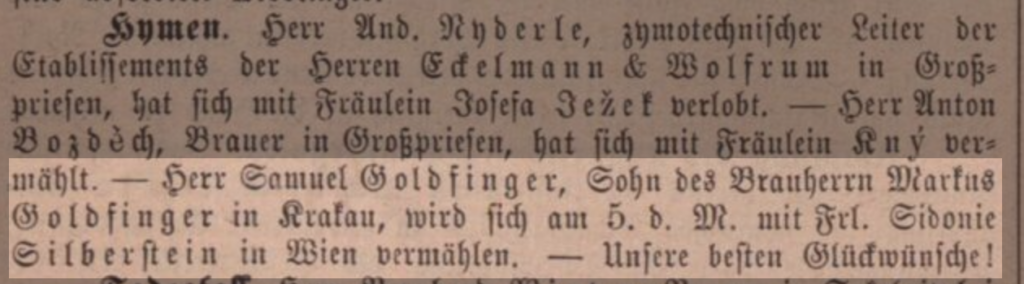

His son Samuel got married in Vienna on March 5, 1889 to Sidonie Silberstein, to which Gambrinus, one of the Austrian brewing and hop trade newspapers at the time, congratulated them. Markus Goldfinger is acknowledged as Brauherr (brewery owner) in Kraków (source).

In the following years, his name appears several times in guest lists of the Austria spa town of Baden bei Wien, e.g here. In later years, his profession is simply described as Kaufmann (i.e. merchant or business man), and I wonder whether it has to do with a shift towards his brewing equipment business.

What got me excited the most though was when I found Markus Goldfinger’s name in a short list of breweries of Kraków, in an index of breweries, distilleries and sugar factories in Austria-Hungary from 1880 (source).

One of the other names appearing in this list is Johann Götz. He was a cousin of Anton Dreher, and was working as brewing foreman (basically head brewer) at Kleinschwechat where he helped invent and brew the very early Vienna Lager, until 1845, when he left Kleinschwechat and founded Okocim Brewery in what is nowadays Poland. While I don’t have definite, conclusive proof, I would say that it’s extremely likely that the few brewery owners of Kraków at the time must have all known each other. At least in Vienna and its suburbs, the brewers all had a Stammtisch where they met regularly. So quite likely, Markus Goldfinger hung out with Johann Götz, someone very closely connected with the invention of Vienna Lager, and discussed the latest innovations in the brewing world.

One of the things I have yet to find out more about is something Tom told me about: Markus Goldfinger apparently owned a number of patents on various brewing equipment he had developed. Unfortunately, in the Austrian Patent Office’s online archive of historic “privileges” (“Privileg” was the historic term for what is nowadays a patent), nothing seems to come up, so either it’s not been digitised yet or is simply not in the archive.

In any case, Tom’s interest in the history of brewing and how he connects it with his brewery was just astounding to me, and definitely showed to me how much thought he put into everything in and around the brewery.

The Community

But Tom isn’t just celebrating the history of brewing with Goldfinger, the brewery also seems to be very community-focused. I first noticed this when we visited the taproom. The weather was quite miserable, there weren’t that many cars parked outside, and yet, the taproom seemed almost full, at a brewery that only serves lager beer styles in a country with a beer scene that is now infamous for its obsession with IPAs. So very clearly, there must be something special about the brewery and the beer that attracts people to just go there (and I guess, quite a few people made it part of their Saturday afternoon walk, or even walked there despite the rain).

We were made really welcome already when we ordered our first beers, everyone of the staff were super friendly and explained everything they offered and did (when I first ordered my Vienna Lager, I asked for a “large” beer, assuming it would be small 0.3l and large 0.5l pours; no, the large option is indeed a Maßkrug, and I was kindly warned about this, LOL).

When you follow the brewery on Instagram (please do!), you will also notice that quite often, visiting food trucks are regularly being announced which also seems to attract quite a crowd. An even cooler event are the monthly tappings of Stichfässer every first Tuesday of the month, just a cask of gravity-poured beer, each time tapped by a different guest tapper from another local brewery. If I lived anywhere near Downers Grove, that alone would be a good reason for me to visit regularly. Most recently, an unfiltered, only briefly lagered version of their Pils was served (a true Keller-Pils), while the month before that, a sneak peek of the Märzen was served, when it still had 3 more months to lager.

The other aspect of community is how Tom interacts with everyone in the beer scene, whether it’s customers at the taproom, professional brewers or beer writers like me. I felt incredibly welcome, and Tom was just such a lovely and generous host that made my visit truly memorable. He also brings together brewers (like inviting guest tappers for the monthly Stichfass), and connected me with head brewer Dusan at Live Oak in Austin, TX (more about them in my next post) for which I’m really grateful. Also, my friend Colin who happened to visit the brewery with his family just a day before us seemed taken aback when he mentioned that he had spoken to Tom, and Tom had remembered him from his only other visit several years back.

So, yeah, Goldfinger Brewing in Downers Grove, Illinois is one of the top places in the US for amazing lager beers and to spend a great time in a vibrant and yet relaxed atmosphere. If you’re ever in Chicago, don’t miss out on their beers, and say hello to Tom if he’s there.

If you want to hear about all this from Tom himself, Craft Beer & Brewing have recorded a podcast with him last year, and if you want to brew one of their beers (and are a subscriber to Craft Beer & Brewing, which I really recommend #notanad), you can find the recipe for Smoked Helles (a collaboration with Fair State Brewing Cooperative) here.