In my research yesterday about beer production statistics in Southern Germany, I came across a curious bit of information, namely that an incredibly large number of top-fermenting breweries operated in Württemberg in the late 19th century, but they on average produced only relatively small amounts of beer.

I then dug a bit further and noticed that statistics for Württemberg made a distinction between “commercial breweries” (using the German term “gewerbsmäßig”, referring to an operation done in order to generate income) and “private breweries” (“Privatbrauereien” in German).

Normally, “private breweries” at the time referred simply to privately owned breweries, as opposed to publicly owned breweries (of which people own shares) or communal breweries (owned e.g. by the citizens of one particular town or city by virtue of their citizenship). But in this case, the private breweries were strangely juxtaposed with commercial ones… so, were private breweries non-commercial?

Turns out, yes: in parliamentary records of the local parliament of Württemberg from 1853, I found a description of what constituted private brewing: it was the non-commercial brewing by Upper Swabian farmers, where it was customary for all farmers who owned larger farms to also own a brewing kettle in order to brew beer for their own use, which included the house drink for the farm workers (the records’ context is a discussion about taxation of malt and how it disadvantages brewing farmers as opposed to those who make wine or cider; the German text uses the word “Obstmost”, presumably referring to any fermented alcoholic beverage made from fruit).

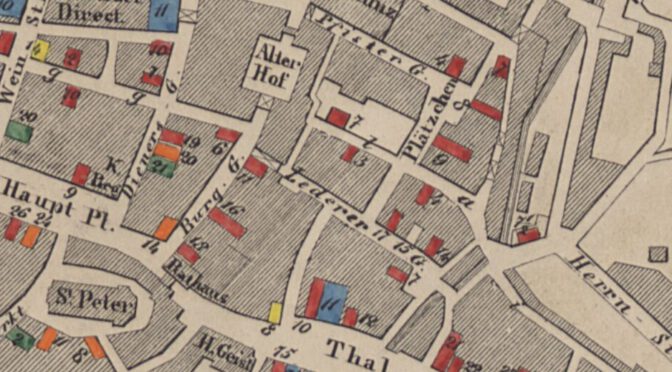

An 1871 article about the brewing history of Württemberg gives more insight: Württemberg has traditionally been more of a wine and cider country. Brewing really only started in 1630 in Stuttgart, but was again banned in 1663 in favour of wine growing. Only two breweries with a brewing monopoly (and owned by the sovereign) were allowed to brew and sell beer. This monopoly was only disbanded on 17 March 1798, and in the years after, private breweries were formed, but only with the territorial gains between 1803 and 1810, new regions were added to Württemberg in which beer brewing was already common (the areas of Württemberg before that time are called Altwürttemberg, lit. Old Württemberg, the newly added parts Neuwürttemberg, lit. New Württemberg). In the following years, beer production increased without the wine or cider production or consumption going down in any way.

In fact, by 1874, Württemberg was the German state with the second-highest annual beer production per capita at 154.3 liters, only surpassed by Bavaria with 240.6 liters.

In later parliamentary records from 1890/1891 (again discussing taxation of malt resp. beer), the beer brewed by farmers as house drink is specifically referred to as top-fermented or white beer, which sounds like private brewers were mostly brewing top-fermented beers.

This is also reflected in the Württemberg brewery statistics for 1896/1897. For that year, 1805 commercial and 4,385 private breweries were recorded. Top-fermented beer was brewed by 336 commercial breweries and 4,383 private breweries, while bottom-fermented beer was brewed by 1,767 commercial and just 4 private breweries. Interestingly, these numbers don’t quite add up, which means that some breweries, both commercial and (probably two) private ones, brewed both top- and bottom-fermented beer.

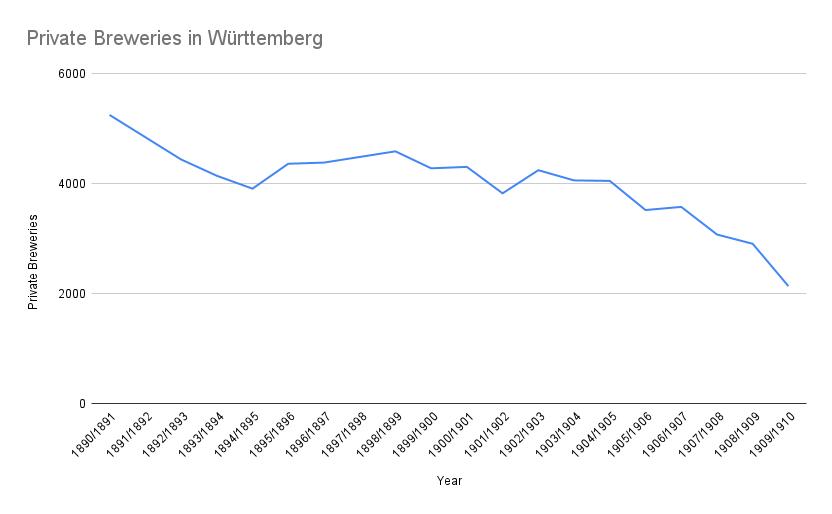

But private breweries weren’t to last: while there were still 5,252 of them operating in 1890/1891, the number fell down to 2,137 in 1909/1910. The number was not consistently going down, though, but rather up and down with an overall downwards trend especially noticeable from about 1904/1905.

Unfortunately, 1909/1910 is the last fiscal year for which I’ve been able to find separate numbers of private breweries.

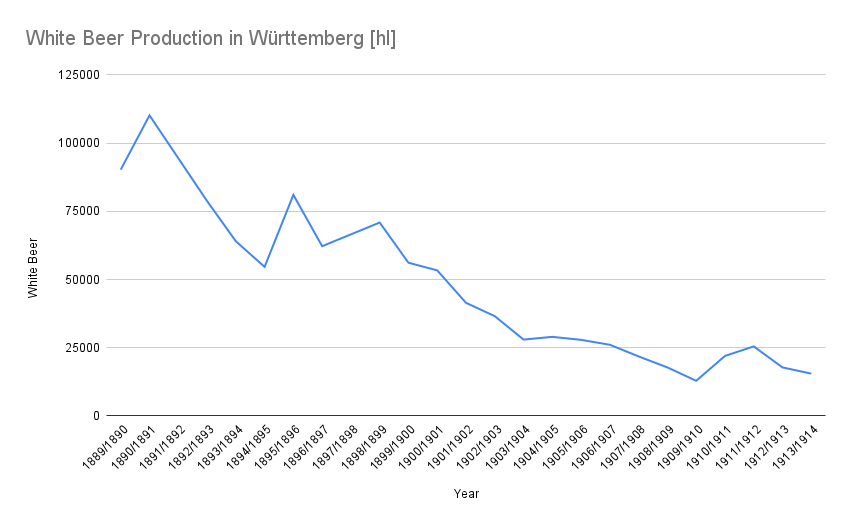

In roughly the same time period, white beer production also fell massively, from 110,168 hl in 1890/1891, down to just 15,524 hl in 1913/1914.

So, to summarise, private breweries were non-commercial breweries operated by farmers in the beer region of Württemberg to brew beer to be consumed in their own household and by their farm workers. The vast majority of that beer was top-fermented. Private breweries were only permitted from 1798 when the beer brewing monopoly of Württemberg was abolished, but only grew in the years after land was redistributed between German states. So while Württemberg had farmhouse brewing in the 19th century, it was not a tradition per se in Old Württemberg, where the common fermented alcoholic beverages were wine and cider, and only gained foothold during the 19th century. None of the sources that I found mentioned whether this farmhouse brewing already existed in the territories that later comprised New Württemberg before they were made part of Württemberg.