I’m currently working on a new project, so as part of that, I’ve been reading quite a few historic descriptions of decoction mashing, in particular triple decoction which historic literature generally describes as the standard mash schedule in Bavaria, Bohemia and Austria around the 1870’s-1880’s.

When I played a bit with calculating the right mash volumes and the mash temperatures, I stumbled upon an interesting property of standard triple decoction: you can’t get it wrong. You actually have to actively try and sabotage it for it to fail.

This is a really cool thing because triple decoction sounds so ancient and complicated and easy to do wrong, and I think that scares a lot of people who then shy away from trying it out, but if you follow a few simple principles, you can’t go wrong at all.

These principles are:

- always pull 1/3 of your total mash volume as decoction

- pull the first and second decoction thick (i.e. mostly malt with little liquid), and the third decoction thin (i.e. mostly liquid)

- bring each decoction to a boil, boil for a bit, then mix back into main mash

- make sure you measure your volumes exactly, work quickly when mixing back, but also mix thoroughly

- when doughing in, give the enzymes some time to get dissolved before starting to pull your first decoction

From a historic point of view, triple decoction was a reliable method to guide your mash through a number of particular ranges of rest temperatures to facilitate the activity of specific enzymes to convert long proteins into shorter protein chains and to convert starch into simple sugar molecules and shorter dextrin chains to both achieve a fermentable wort and a good mouthfeel, without requiring a thermometer.

And when you apply some maths, and draw a pretty graph, it really shows that all you need is the ability to vaguely judge your initial mash temperature to be between somewhere slightly above room temperature and slightly below tepid, and everything falls right into place, provided you follow the principles above.

The general equation to calculate your decoction volume is:

decoction volume = total mash volume * (target temperature – start temperature ) / ( boil temperature – start temperature)

If we assume the total mash volume to be 1, and our decoction volume to be 1/3, we can rewrite this to

target temperature = start temperature + 1/3 * (boil temperature – start temperature )

Based on this, we can easily calculate whole temperature series if all we do is repeatedly pull decoctions that are 1/3 of the whole mash volume, bring them to a boil, and mix them back.

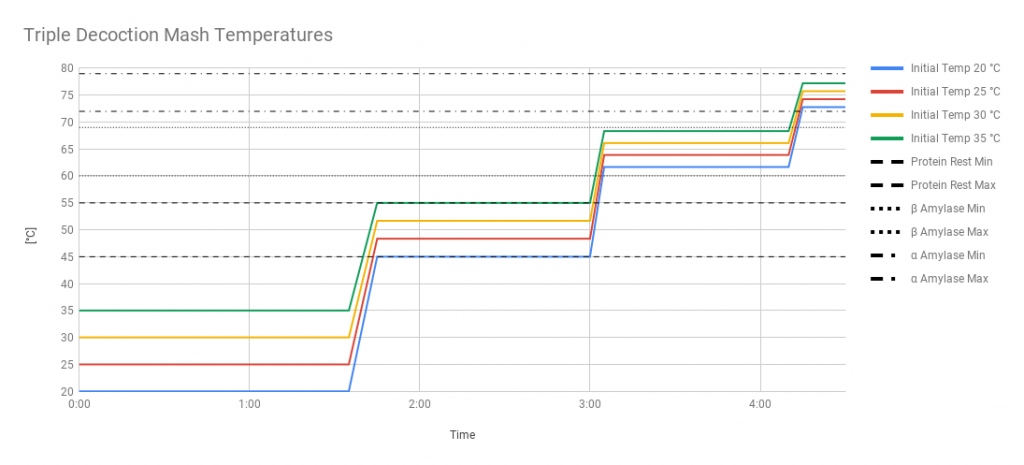

I’ve done this in a spreadsheet, and put this into a nice temperature/time chart to indicate the time schedule your mash steps would follow. In total, I’ve done this with four different initial temperatures: 20, 25, 30 and 35 °C. This is a rather wide temperature range, but it’s also one where most people could easily and correctly judge whether a liquid is within that temperature range just by feeling with their finger or elbow. To keep the chart readable, I’ve only added the main mash temperature, and left out the temperature curves of the decoctions. To account for cooling during mixing back, especially so on a homebrew scale, I assumed a boiling temperature of 95 °C instead of 100 °C.

In addition, I’ve marked the temperature ranges in which you reasonably want to keep your mash to do a protein rest, as well as to give the alpha and beta amylases good conditions to do their work.

When you now look at the chart, it is very noticeable that at all stages (protein rest, maltose rest, saccharification rest/mash-out), all our target temperatures fall within the desired temperature ranges. The further we go, the more all the temperature curves converge towards a narrower and narrower temperature range, even though we started with a very wide one. This makes it very hard to screw up, even if you e.g. slightly miss your target temperature after your first decoction: you will still be well within the desired temperature range.

In addition to that, when you bring up your decoctions, in particular the first one, to a boil, they go through these temperature ranges as well. Some modern mash schedules recommend doing at least a saccharification rest to optimally use the enzymes that will later get destroyed, so you can have an infusion step mash within your decoction. Even if you don’t do it, unless you heat up very quickly, your decoction will at least partially convert when you heat it up.

And this is why your triple decoction mash can never fail: when bringing your decoctions to a boil, they will partially, if not mostly, convert, and then release more starch during the boil, which will then be fully converted in the main mash. There are two decoctions where the enzymes get into the right temperature range to convert starch into sugar, and there are two rest steps where the enzymes have even more time to convert more starch into sugar. Your whole mash goes through the right temperature so many times, it will eventually be fully converted. And to get into these right temperature ranges, all you need to do is follow a few simple principles. And if you want, you could even do this totally without a thermometer.

For most modern malts, triple decoction is possibly a bit to harsh, in particular when it comes to the extended protein rest which could potentially be very damaging to foam stability. For this, you can also employ an enhanced double decoction, in which you start at the same temperature as a triple decoction, but pull double the volume for the first decoction, and do a step mash of your first decoction before boiling it. That way you keep the intense treatment of your malt, but can keep the time within the protein rest range to an absolute minimum.

Terrific explanation. You don’t state this explicitly, but blood heat and boiling are the two temperatures that you can easily determine without a thermometer. Triple decoction enables you to start when the mash “feels warm” and get everything right. I suspect that means the initial temperature range might be even tighter than you indicate (although I am aware there were also cold mashing techniques).

Yes, blood heat is probably even more accurate.

What I mean is that starting with blood heat, 37 degrees, the first decoction, purely arithmetically, will bring us up to 56 degrees, and the second up to 69 degrees, which is staggeringly close to the perfect temperatures for the protein rest and saccharification rest. If I were looking for proof that God wants us to make beer, this would be it.

That is indeed very interesting. I’m not sure the implicit comparison to other forms of mashing is fair, though. The idea that before the invention of the thermometer you could use a fixed ratio of the ingredients to get the mash temperature in the right place for conversion works for other mashing systems too. If you have a well, its fairly constant year-round temperature and boiling give you two fixed points to find any hot liquor temperature you want. Eg 3 parts boiling and 1 part at 8 degrees would give you a hot liquor temperature of 77, which might give you a temperature in the high 60s after mashing in. In other words, you could learn by trial and error which ratio of boiling water to well water gave you the best results and follow that.

The other thing to bear in mind, of course, is that the best mashing schedule might vary for different beer styles. A lot of people argue that a turbid mash is necessary for lambics, for example, and Victorian writers said limiting saccharification to preserve a certain amount of maltodextrin was necessary for stock ales for the nutrition of ‘cask yeasts’. In effect, for some beers a triple decoction which hits all the enzyme groups would not give the best beer.

I haven’t done a decoction mash yet, but am interested in giving it a go some time. How do you pull thick and thin? Do you simply mean having more of the actual grain in the 1/3 that I take out?

When pulling a thick decoction, I use a slotted spoon to scoop out the malt and put it in a measuring cup. I make sure that there is still some liquid in the decoction, so as not to scorch it when heating it up later. For thin decoctions, I do the exact opposite, i.e. I use the slotted spoon to prevent malt from getting into the measuring cup when I’m scooping out liquid. I hope that explains it well enough.