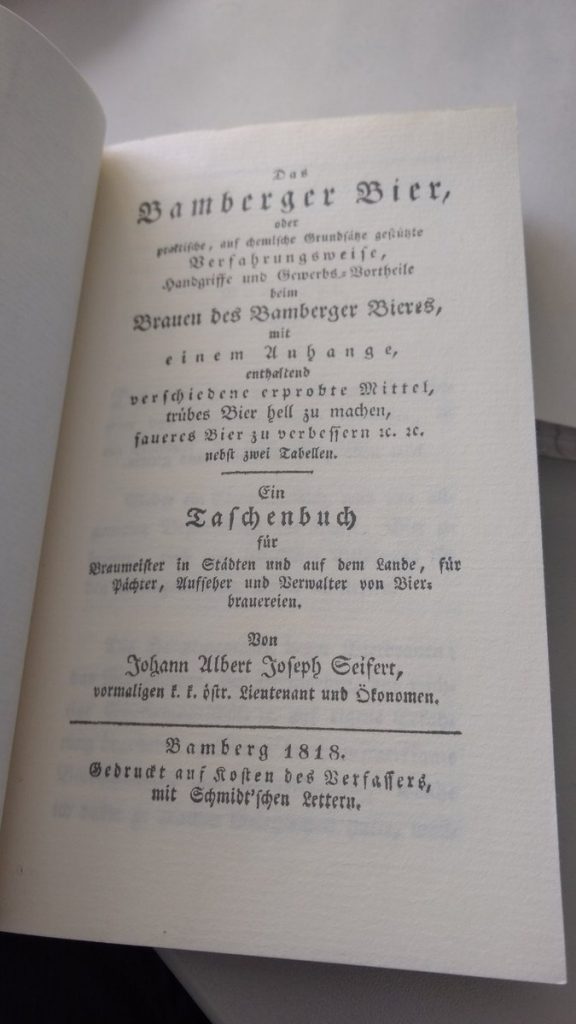

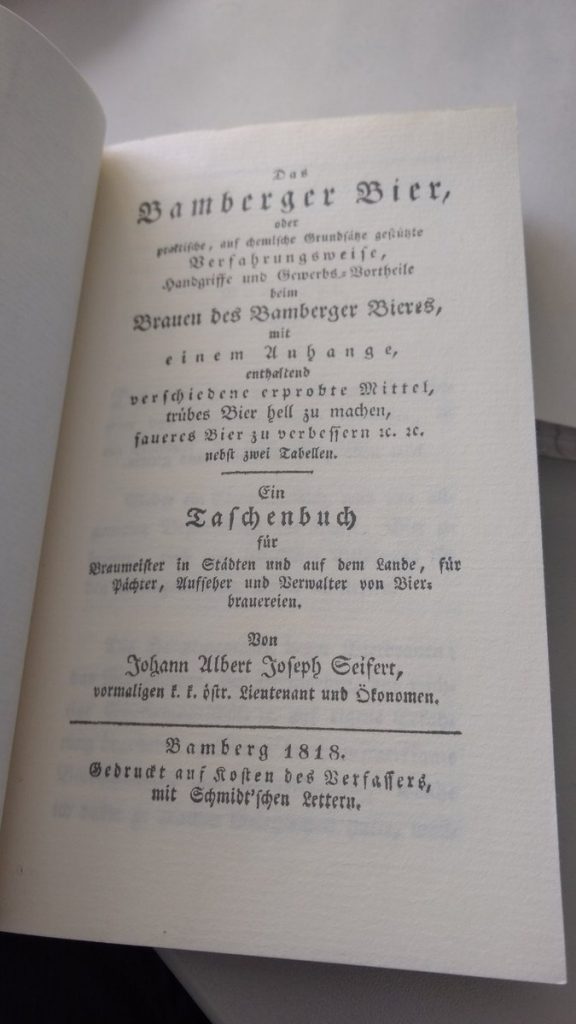

I recently bought a reprint of a historic book by the name of “Das Bamberger Bier”, written by Johann Albert Joseph Seifert. It gives an overview over the ingredients and processes used specifically in Bamberg to produce beer. As I already said on twitter, it’s full of gems.

Let’s start with the ingredients: the malt. The book contains a description how to let the barley germinate, how it needs to be turned, when it needs to be dried, and so on. What caught my eye in the production process was a single paragraph that essentially says that brewers with enough space in their buildings to produce air-dried malt will have a good, pure, wine-coloured beer. I interpret that as a suggestion to use air-dried malt (“Luftmalz” as it’s often called in historic German brewing literature) for brewing beer if possible.

You can’t produce air-dried malt during the winter, though, as a night of frost can destroy all your drying malt. So kilning your malt is still recommended during these times.

Then the water. According to the author, rain water is the best for brewing, but at that time, cisterns to collect had already fallen out of use, so brewers would have to work without it. River water, if clean enough, was the next best choice, that is if the brewer has access to it. Well water was considered to be of the worst quality, and required thorough boiling before it was usable by the brewers.

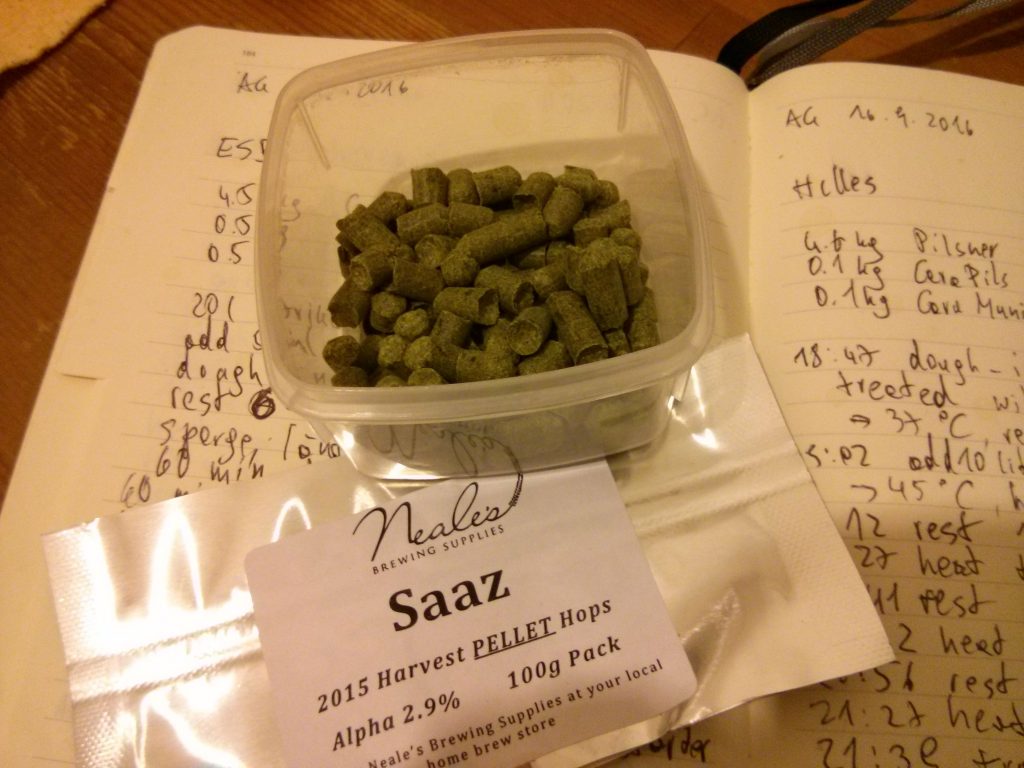

As for the hops, Bohemian hops were commonly used in Bamberg at that time. The author then gets mysterious: he went to school in Komotau/Chomutov, only a few kilometers away from Saaz/Žatec, and he alleges some dodgy things are going on with customs between the Bohemian-Bavarian border without going into details. He does propose though that hops more local to Bamberg can produce equally good beers.

The yeast that brewers in Bamberg used was mostly bottom-fermenting. Probably it was all bottom-fermenting by today’s standards, but the differentiation 200 years ago could not be done on a morphological level (nobody knew what yeast really was), so instead yeasts were distinguished how they cropped: so-called “Oberzeug” is top-cropped yeast, and usually synonymous with proper top-fermenting yeast, while “Unterzeug” was bottom-cropped, all the stuff that was on the bottom of the fermenter at the end of the fermentation. Brewers weren’t keen on using top-cropped yeast, but if nothing else was available, they would still use it, in particular for winter beers.

Fermentation was done cold, as in most parts of Bavaria at that time, at least for the higher-strength lager beers or summer beers, at about 12 °C, while the Schenkbiere or winter beers, running beer that was brewed during the winter to be served after only a few weeks of maturation, was fermented warmer, at 18 °C or warmer.

Now about the process itself: while in most parts of Bavaria a triple decoction mash very common, Bamberg is quite different. The specific mashing regime is often attributed as the reason why beers from Bamberg are as peculiar and more alcoholic than other lager beers at that time.

So how mashing in Bamberg essentially worked 200 years ago is infusion mashing: grind the malt, add water of a certain temperature, let it stand for some time until all sugars have been converted, then lauter. Then do a second mash with water that’s a bit hotter, again let it stand for some time, then lauter again. In some way, the method bears a lot of similarity to classic English mashing. Homebrewers may also recognize it as similar to “batch sparging”.

You essentially start off to dough in the malt to a very thick consistency. The book is not very clear on how much water per amount of malt this would be, but from my own experience, I would guess about 1.3 liters per kg of malt, because that that’s about enough to wet all the malt, but not to have much free-standing liquid afterwards.

The water is mixed from 2 parts of cold water and 1 part of hot, nearly boiling water. If we assume “cold water” to mean about 10 °C and “hot water” to be between 95 and 100 °C, the water would have a temperature of 38 to 39 °C, and the resulting mash would end up at about 34 °C. That’s quite close to the temperature of an acid rest, which is done at about 35 to 45 °C to lower the pH of the mash. At this temperature, the mash is left to stand for about 15 minutes.

The next step is to do the first mash. Water is added (the author is unclear about how much, though) that was previously mixed from 2 parts of hot water and 1 part of cold water. If we make the same assumptions as before, we come up with a strike temperature of 66 °C. The resulting temperature of the mash will be lower. Since we do not know how much water we can add, we can at least assume that we need to add so much that we hit a mash temperature of 60 °C or higher. This mash, after thorough mixing, is then left to stand for an hour. After an hour, the first lautering starts, where the wort is first recirculated until it runs clear, then all wort is completely drained and put on the coolship.

Then the second mash is conducted, with water mixed from 3 parts of hot water and 1 part of cold water. That would mean 73 °C, and the resulting mash temperature will probably be around 68 to 70 °C. This again is thoroughly mixed, and left to stand for an hour, then again recirculated, and completely drained.

Optionally, you can do this even a third time, with hot water only, and this third wort would be used for small beer only. This small beer was called “Heinzele” or “Hansle” in Bamberg. Some brewers would also use cold water only for this final mash.

For lager beer, only the first and second wort was used. The hops were boiled in a very particular fashion, by what was called “Hopfen rösten”, or “roasting the hops”, where a small amount of wort was used to boil the hops for an hour, then the hops were removed (so that they could be reused for the Heinzele), and the hopped wort was boiled with the rest of the wort for another 60 to 90 minutes. The author did not like this practice, and said that beers made without roasting the hops would actually taste nicer and keep better.

After the wort was fully boiled, it is cooled as quickly as possible in a coolship, then moved to the fermenter, where yeast is added. After the fermentation has finished, the young beer is moved to casks, where it is left with the bungs open so that it can expel any remaining yeast and clear up. These casks were unpitched, but instead just washed with hot water and burnt with a small amount of sulphur. Since most other Bavarian beers were filled into pitched casks, this will very likely also have had an influcence on the flavour specific to beer from Bamberg.

As for the recipe itself, I converted the amounts of malt and hops provided in the books and ended up with these rough parameters: it most likely had an OG of about 14.5 °P (1.059), about 5 % ABV (depending how highly fermenting the lager yeast strain was), and used as much as 8.75 g/l of hops. Due to the hop roasting, alpha acid extraction was probably quite inefficient though, so the bitterness of the beer was probably at about 35 to 40 IBU.

To produce 20 liters of this beer, 5.4 kg Munich malt and 175 g Saazer or Spalter hops should suffice. Use a strike water calculator of your choice to find the optimal amounts of water for the different mashes. A bottom-fermenting yeast with a relatively low attenuation would be most suitable for this style. My personal preference is White Labs WLP820.

Besides a description of ingredients and brewing processes, the book also contains a list of all breweries in Bamberg at that time, 65 in total, including the owner’s name, the brewery’s or pub’s name, the address, the amount of malt used, and the amount of beer produced from it. Of the breweries that are still around in Bamberg, some of them do appear on this list:

- “zum Spezial”, run by Peter Brust, 2nd district, house no. 593, produced 789 Eimer beer and 394 Eimer “Nachbier” (Hansle) from 306 Schäffel and 5 Metzen of malt.

- “zum Greifenklau”, run by Johann Müller, 3rd district, house no. 1333, produced 835 Eimer beer and 417 Eimer Nachbier from 325 Schäffel and 1 Viertel of malt.

- “zum Fäßlein”, run by Anton Kröner, 3rd district, house no. 1004, produced 364 Eimer beer and 182 Eimer Nachbier from 141 Schäffel, 2 Metzen and 2 Viertel of malt.

Ron Pattinson has the full list. These breweries, while still around, weren’t by far the largest though. The place with the highest beer production was “zur weißen Taube”, with a whopping 1379 Eimer of beer and 689 Eimer of Hansle.

Looking at the numbers, there’s also an interesting pattern showing up: for every 2 Eimer of beer, 1 Eimer of Hansle was produced. And also the ratio of beer to malt is relatively consistent, at about 2.5 to 2.6 Eimer of beer per Scheffel of malt.