Just recently, I came across the J.C. Jacobsen archive of the Carlsberg Foundation. In there, a number of letters written by or address to J.C. Jacobsen are publicly accessible and transcribed.

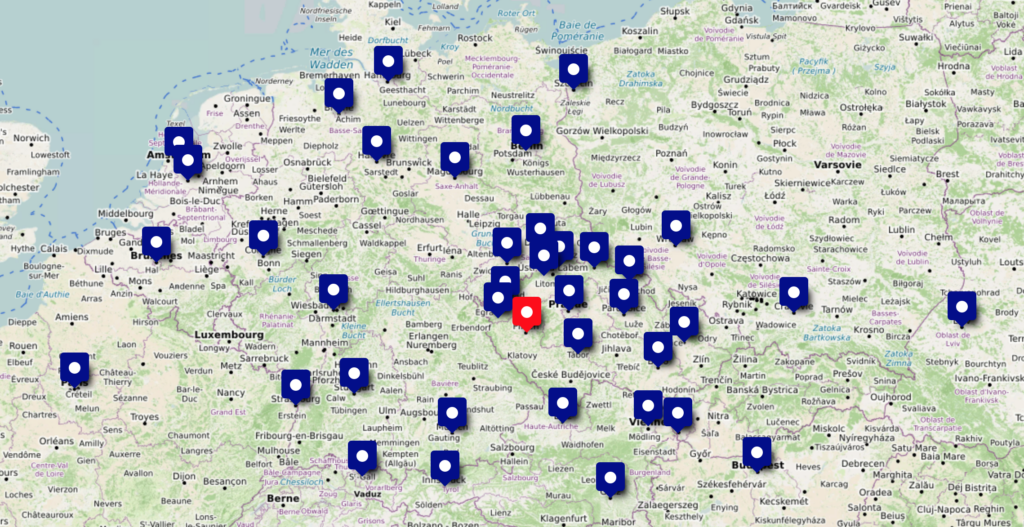

Going through the archive, I noticed how well-connected J.C. Jacobsen, the founder of Carlsberg brewery, was in the Central European brewing industry: he considered Gabriel Sedlmayr of Spaten his “master teacher”, he visited the breweries of Munich, Vienna and Plzeň, conferred with Franz Fasbender, the editor of a Vienna-based brewing journal, and even visited Johann Götz in Okocim.

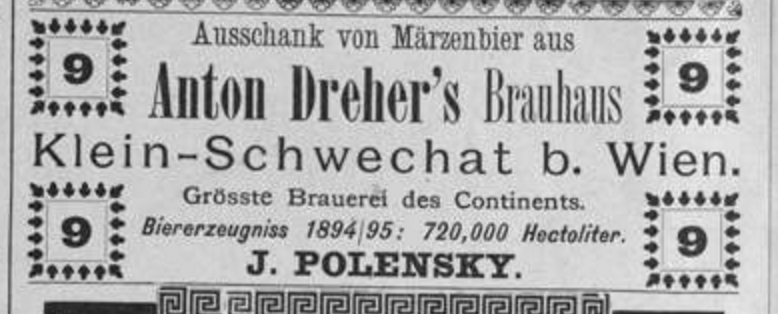

As someone with an interest in the history of Vienna Lager, I was of course curious about what he had to say (if anything) about the Dreher breweries. And I found plenty, with details that I had never read anywhere before.

In these notes from the 1860s, we learn this about the brewery in Kleinschwechat:

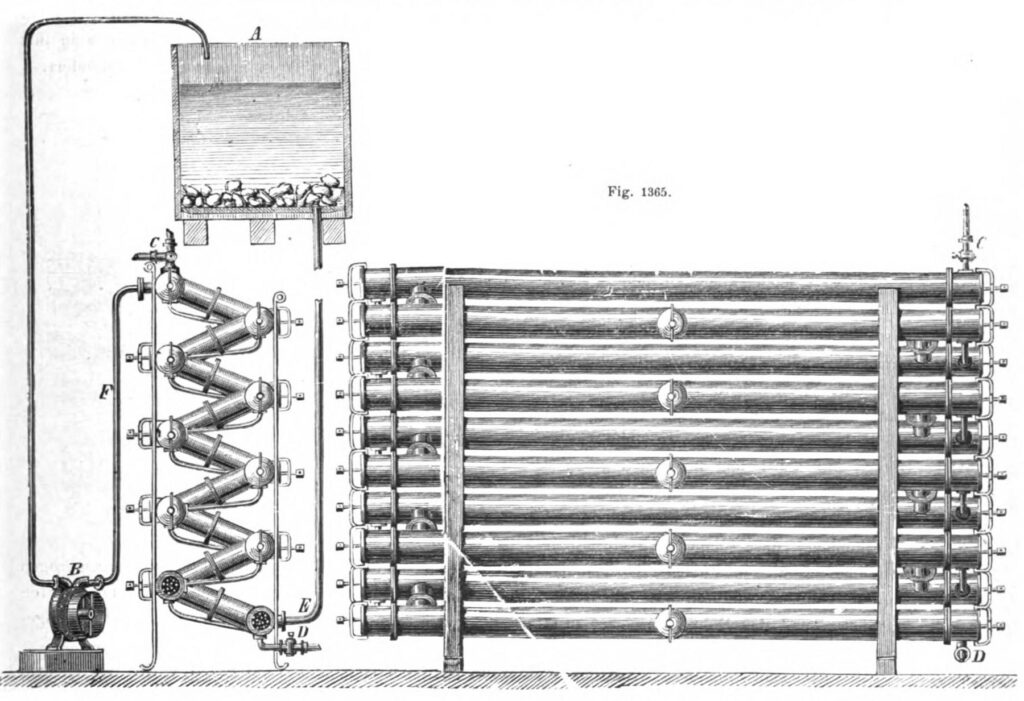

The malting floors were tiled with “Kelheimer Platte”, limestone tiles from Kelheim in Bavaria, something that was very common in Bavarian brewing and basically considered to be the industry standard. The mash tuns and vats were all made of wood. Jacobsen noted that the “mash machine” (presumably the stirring apparatus) was the same as in the Carlsberg brewery. All kettles were made from copper, while the coolships were made of tinned copper. The cooling apparatus in use was a 10 tube cooler by [Vinzenz] Prick, presumably one similar to this one:

With the cooling system, wort could be chilled down to 4°R, at most 7°R (5 resp. 8.75°C).

About the Dreher brewery in Steinbruch/Kőbánya we learn which beers they brewed:

- Kronenbier, “very bitter, like Pilsener”, with an OG of 12.5° Balling

- Lagerbier at 13° Balling

- Märzen at 14° Balling

- Double Märzen at 15° Balling, which he compared to one of his beers in colour, but “finer in taste”, aged for 4 months, and hopped with a mix of Saaz, Auscha and Styrian hops.

For the paler beers, only the finest hops were used, as the malt flavour was not predominant.

Apparently different malts were produced for the beers: for Kronenbier and Lagerbier, the malt was kilned at 45°C (measured between the kilning floors), while for the other beer types, it was kilned at 85 to 90°C.

The cooling apparatus used in Steinbruch was apparently the same as in Kleinschwechat, built by Prick, and the coolships were made of iron.

In 1868, Carl Jacobsen, J.C. Jacobsen’s son, noticed differences in the construction of fermenters: at Sedlmayr’s Spaten brewery, oak was generally used, while Dreher was in the process of switching to fermenters to larch wood. There were apparently two schools of thought: oak was preferred by some because it did not chip and was thus easier to clean, while those who preferred larch said that it was smoother compared to oak and thus easier to clean. Carl had not formed an opinion on it at that point.

He also reported about breweries that struggled with beer turning sour: the previous summer, Sedlmayr’s Spaten brewey had to dump 20,000 Eimer of sour beer, and Dreher in Vienna had also lost enormous amounts of beer that way.

He also made an interesting observation about the Munich beer: he described it as slightly darker than Vienna Märzen (the export beer that was also available in Copenhagen at the time, to provide his father with a reference), and that it must have been darker previously, but always brewed without any roasted malt. Since we know the colour of Vienna Märzen from six years later, we can deduce that Munich beer (or at least some of them) were probably more on the amber side (rather than straight up brown) in terms of colour at the time.

In yet another letter from January 1868, Carl also mentions a glass fermenter at Kleinschwechat, which was in use at the brewery for a few years by then. The bottom was slightly cracked, but overall it was still usable. The yeast settled more firmly than in wooden fermenters. The brewery was happy with the fermenter and working on building two more.

He also had an opportunity to compare malt samples: the malt from the Hütteldorf brewery was very similar to the one from Kleinschwechat, while their beer was somewhere between a Munich and a Vienna lager. In a previous visit, he found their malt to be more strongly malted, but that may have been coincidental. The malt from Liesing brewery on the other hand was poorer in quality, with more hard kernels, which Carl blamed on the construction used mill used at Liesing.

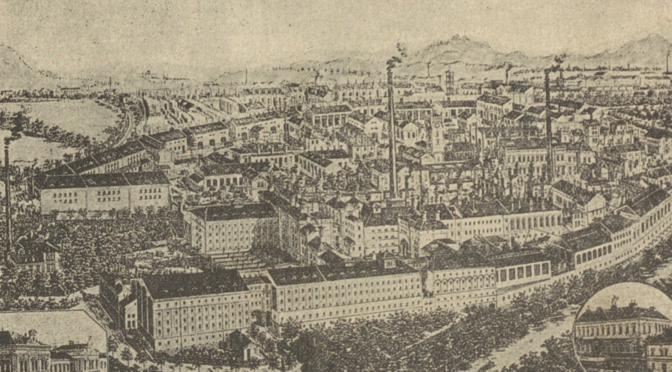

Carl Jacobsen also visited the Dreher brewery in Micholup (Michelob) near Saaz in 1868, and wrote a letter to his father about it. Carl thought the Micholup brewery was a “beautiful and good” brewery, but that the absolute highlight were the fermentation cellars, completely underground, 7 metres high and enclosed in enormous ice containers. The fermentation cellar contained 84 fermenters of 40 Eimer each, so not a large volume compared to the other Dreher breweries. They were all raised so that work could be done underneath them, but at the same time also reachable from the top via a wooden floor.

The fermenters were filled with wort at a temperature of 4°C which rose to 6°C, sometimes 7°C during fermentation. Due to the good cooling capabilities of the cellar, ice floats were never needed, and in fact, none existed within the brewery.

J.C. and Carl sent each other letters about many other lager-brewing-related topics, but even just what I was able to find about Dreher breweries was very enlightening and contained details I had not come across in my research for my book about Vienna Lager (which I highly recommend if you’re further interested in the topic).