More than two years ago, I wrote an article discerning accounts from 1834 about various brewing methods as they were practiced in Germany and Austria, in particular Munich, Augsburg, Prague and Vienna, as part of #BeeryLongReads. I even won great prizes for it:

A lot has happened since then, not only did I gain more experience in blogging, I also published a book about historic beer stuff. So this time, I want to follow up on the theme and discuss the specific differences in decoction mashing from a late 19th century point of view.

Franz Cassian published a book named “Die Dampf-Brauerei. Eine Darstellung des gesammten Brauwesens nach dem neuesten Stande des Gewerbes.” in 1887 in which he talks about the state of the art of brewing at that time. I only came across this book recently, and found it particularly interesting because it contains a whole section with nothing but detailed descriptions of various types of decoction mashing and their differences.

Now, if you’ve never heard of decoction mashing before, let me just quickly describe it to you: when brewing a beer, the brewer uses the enzymes in the malt combined with hot water to convert the starches in the malt to sugar. In order for the enzymes to work under optimal conditions, this needs to happen at certain temperatures. Different enzymes do their stuff at different temperatures, so if you wanted to activate the enzymes to do their thing, you’d go through these different temperature steps so that each of them can work under optimal conditions. There are essentially three different ways of doing this:

- by adding more hot or boiling water (which can make the mash very thin)

- by heating up the mash until the right temperature is reached (which can be tricky if you don’t have exact temperature control)

- by taking a part of the mash, boiling it, and mixing it back (which takes a long time and uses up a lot of energy and fuel)

Some brewing traditions even just keep a single temperature, but in some ways, they’re just a simplification of methods (1) and (2), which nowadays are called infusion mashing. Method (3) on the other hand is called decoction mashing and is very traditional in Bavaria, Bohemia and Austria to a certain extent, and only used to be practiced there. At the time, brewers swore by it and exclaimed that decoction mashing was absolutely essential for their local beer style. Even today, decoction mashing is necessary in the Czech Republic if a brewer wants to call their beer a Czech beer.

Modern German breweries have gone off it for various reasons though: energy efficiency is one of them, as infusion mashing doesn’t use up nearly as much energy. Another reason is the perceived lack of impact on quality. This is relatively controversial, but there exist studies that claim that the difference of decoction mashing and infusion mashing cannot be smelled or tasted by your average Joe beer consumer, while some brewers still swear by it. An experiment at Brulosophy that compared whether people could taste a difference between triple-decocted beer and one produced by single infusion mash failed to gain significance. Upon closer analytical examination, differences between worts and beers produced through infusion mashing resp. single, double and triple decoction mashing can be measured.

Decoction mashing nowadays is mostly distinguished by how many decoctions are pulled (1, 2 or 3), the consistency of the decoctions (thick or thin), and which temperature steps you’re going through. With modern brewing science as a helpful tool, we exactly know what’s happening at each temperature step and which enzymes will be the most active, and we know about the destructive force boiling a decoction wields on the diastatic power (the ability to convert starches to sugar) of the partial mash. Even though brewing science in the late 19th century had already made great progress, brewing as such was still a craft and findings of brewing science were not necessarily immediately incorporated into the knowledge and toolset of a brewer.

With this context, let’s look at what Franz Cassian wrote about the specific styles of decoction mashing. He distinguishes three main methods, the Munich method, the Viennese method, and the Bohemian method. He identifies two main differences between those three methods: first, the type of malt that is used in mashing, and second, the way the mash is treated in relation to temperature, the number and consistency of individual decoctions, as well as boiling durations. The rest of the operation, like boiling and chilling the wort as well as fermenting and lagering the beer, he says, are essentially the same.

He then goes on to describe the different malts that are used for each of these methods: for the Munich method, highly kilned malts are being used, while for the Viennese method, the malt used produces a beer with reddish-brown colour that is lighter than Munich beers. The malt itself is very aromatic. The typical malt for Bohemian beers, he writes, is very pale, leading to an almost wine-like colour of the beer. The malt is kilned as such low temperatures that the author describes them more as dried than kilned. He also mentions an interesting detail: some Munich breweries at that time had started kilning their malt to a lower temperature, and then adjusted the colour of the beer with Farbebier.

Farbebier, literally “colouring beer”, is an extremely dark beer made from large amounts of debittered roasted malt that can be used to adjust the colour of beer without imparting the beer with too much roasted aroma and flavour. Since it’s just beer, mixing Farbebier with pale beer was compliant with the Bavarian prohibition on adulterating beer or substituting its ingredients. It was the only legal food colouring for beer at that time, and still is to this day if you want to advertise your beer as being compliant to the Reinheitsgebot.

Kilning at lower temperatures has a good technical reason: it destroys fewer of the enzymes that are required for starch conversion, and makes the malt more convertible, which in turn makes it easier for brewers to work with it. Using Farbebier was really just for matching customer expectations. This is what some Munich breweries allegedly still do nowadays: American beer consumers expect an Oktoberfest beer to be amber-coloured instead of the golden colour of modern Festbier, so Farbebier is used to adjust the colour for the American exports without impacting the flavour.

This description with Bohemian malt being the palest, Munich malt being the darkest and Viennese malt being in-between these two also reflects modern base malts: many maltings in Germany will produce and trade at most three base malts: Munich malt, Vienna malt and Pilsner malt. Only a few specialty malt producers offer a wider range of base malts, from extra-pale malt even paler than Pilsner malt, to Pale Ale malts more suitable for British and American styles, to proprietary malt blends for producing wort with a distinct red hue.

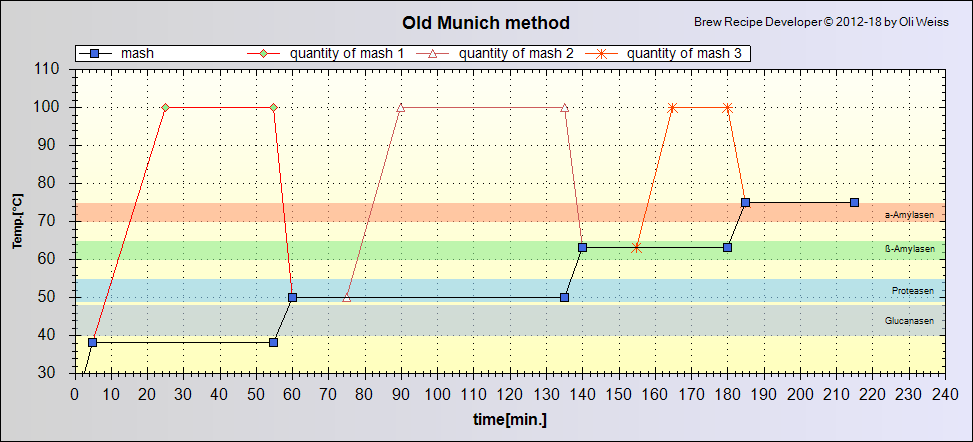

Besides the malt, the even more important distinction in brewing methods was the mashing itself. For Bavarian mashing, the author distinguishes four types: the old Munich or old Bavarian method, the new Munich method, the Augsburg method, and the Franconian method.

Old Bavarian Method

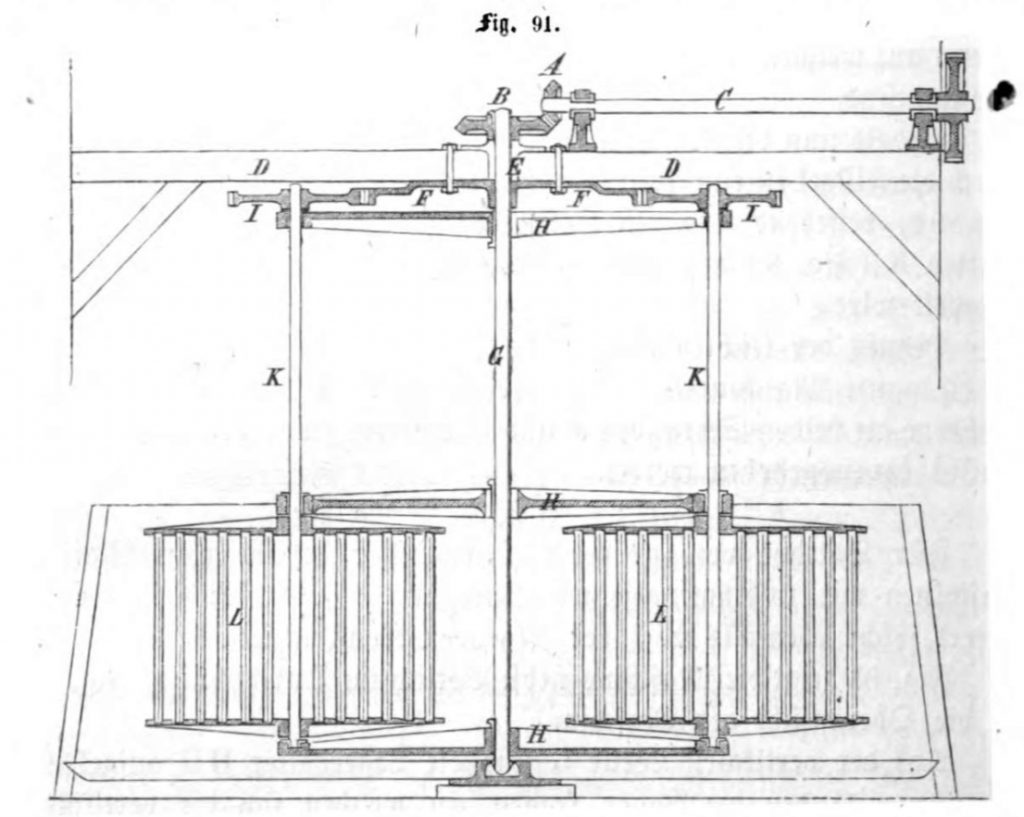

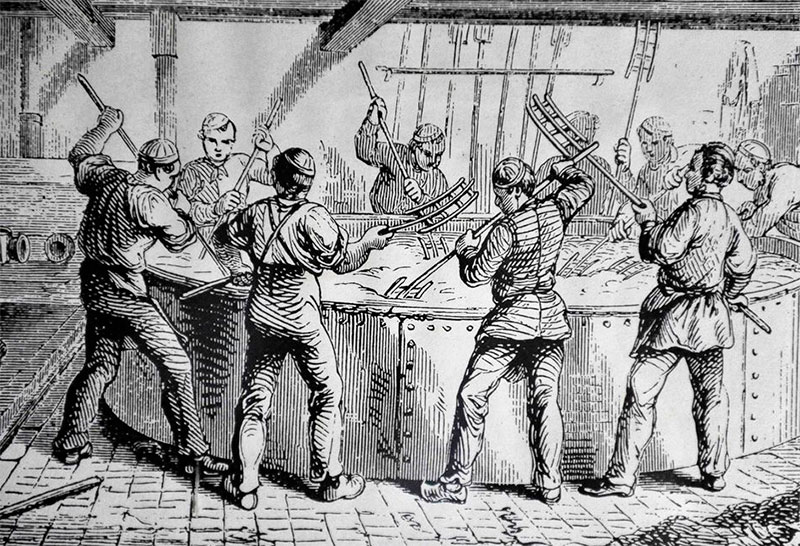

At the time of the publication of this book, this method was barely in use anymore. It used to be common for primitive breweries with not a whole lot of equipment, so most of the work was manual labour: mashing and lautering was done in the same vessel, so mash tuns had a false bottom, stirring was only done by hand, and hot water was added through simple tubes attached on the side of the mash tun going underneath the false bottom. Underneath the mash/lauter tun, another vessel, the “Grand”, was installed, which was large enough to contain all the collected wort.

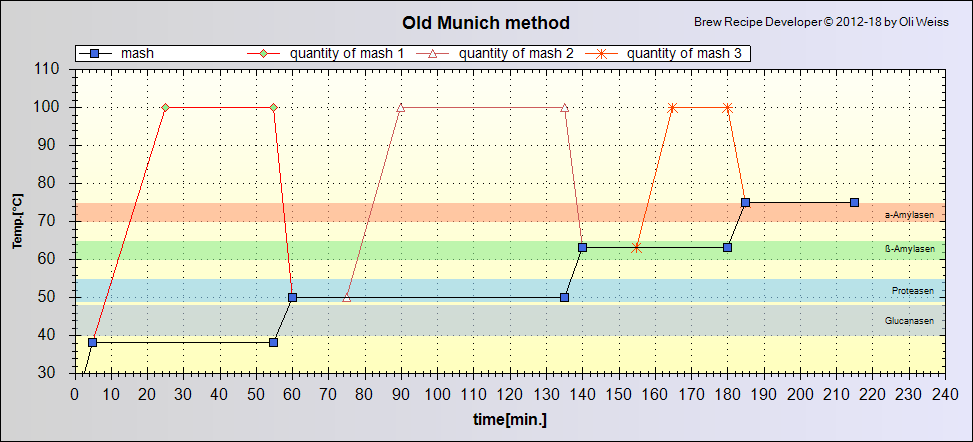

The brewing process worked like this: for every unit of malt (by weight), 8 times that amount in water was required. One third of the water is added to the mash tun, while the rest is slowly brought to a boil. While the water heats up, the malt is doughed in. Bringing the water to a boil could take 3 to 4 hours, so that’s how long the malt was doughed in at a cool temperature. When the water is boiling, it is added very slowly to the mash, and mixed thoroughly, so that when all the boiling water is mixed in, the mash is at a temperature of about 37 to 38 °C.

Immediately, one third of the volume (as a thick mash) is put back into the copper, and quickly brought to a boil, where it is boiled for half an hour and then slowly mixed back into the main mash while constantly stirring. The resulting temperature of the mash should then be at about 45 to 50 °C, and will be mashed (stirred) for another 15 minutes to liquefy the mash. Then again, a third of the volume (again a thick mash) is put into the copper, and boiled for 45 minutes, and again slowly mixed back to reach a mash temperature of 60 to 63 °C. More stirring happens for 15 minutes, until the the third decoction can happen:

A third of the mash, this time a thin mash, is put into the copper, boiled for 15 minutes, and – you should know the drill by now – slowly mix it back under constant stirring to reach 73 to 75 °C. With that, the mash boiling is concluded, but not the mash itself: it gets stirred until the mash is fully converted. Nowadays, this would be verified with an iodine test (an iodine solution turns from brown to blue if the mash still contains unconverted starches), but back then it was determined by how quickly the hard matter in a sample of the mash sinks down the bottom of the vessel.

When mashing is concluded, it rests so that the grains can sink to the bottom of the vessel, which usually takes 30 minutes. Then the tap of the lauter tun is opened and the first wort is drawn into buckets. The wort is poured back onto the mash until it runs clear, then the wort is collected in the Grand, from where it is transferred to the copper. The grains are then further rinsed by pouring hot water on top: 30 liters per 100 kg of malt. The resulting wort is added to the wort. More hot water is then poured on top of the grains, at 50 to 60 liters per 100 kg of malt, and the resulting wort is used to brew a weak beer called “Schöps”. The final runnings, at 30 to 40 liters per 100 kg of malt, are called the Glattwasser and are used for distilling.

New Munich Method

Unlike the old Bavarian method, the new Munich method employs more sophisticated equipment and a certain degree of automation using steam engines. Mash and lauter tuns are separate, and no full-sized Grand is used anymore. Doughing in happens with a pre-masher, and the initial mash temperature is reached by using water from a hot liquor tank. The Mash tun is set higher than other equipment so that decoctions can be transported using gravity, and mixed back using pumps. Like the old method, the new method still employs three decoctions, two thick ones and a final thin one. But due to the high degree of automation, exact timing, and a hot liquor tank that can be used for quick temperature corrections, the whole process is meant to be quicker and more precise and therefore more reproducible and repeatable.

The temperature steps are slightly different: the first decoction is drawn at 30 °C and boiled for 15 to 45 minutes to bring the mash to 55 °C. The second decoction is boiled for 15 to 45 minutes to bring the mash to 65 °C, and the final thin decoction is boiled for 30 to 45 minutes to bring the mash to 75 °C. The amount of sparge water that is used is two thirds of the initial water volume.

Augsburg Method

The typical method for Augsburg is “auf Satz brauen”, which is pretty unique and quite different from the class Bavarian or Munich decoction. The ratio of malt to water is 1:6 by weight. The mash tun has a false bottom, which gets covered with hop leafs to help prevent the mash from getting sour through lactic acid fermentation. Doughing in is done with so much cold water that the resulting mash is quite thin and easy to stir, and then rested for 4 to 5 hours. Then the cold malt extract (you probably can’t call it wort yet), called “kalter Satz”, is then drawn off and put aside. The rest of the water is brought to a boil, and then a few liters (unfortunately, the author is not very clear here) of the kalter Satz are added to the boiling water which makes the proteins in it coagulate. The proteins are removed, then the hot water is slowly mixed into the drained main mash that has been hacked up before. After all the hot water has been added, the kalter Satz is also mixed back into the main mash, after which it should have a temperature of 60 to 65 °C.

Then the mash is stirred until it has properly liquefied, only to rest 15 minutes before the “warmer Satz” is drawn off. This is just like lautering: first, wort is drawn off and poured back into the mash until it runs clear. Of all the wort, two thirds go into the copper, while one third is put aside. The wort in the copper is brought to a boil as slowly as possible to maximize the amount of hot break for a clearer wort. The boiling wort is poured back into the main mash, which again should have a temperature of about 65 °C. At that point, the mash shall be stirred to continue starch conversion.

Then, the thick portion of the mash is drawn off into the copper and boiled for up to 2 hours, until no more hot break appears on the surface. It is then mixed back into the main mash to get it up to 70 °C. Then, the wort that was set aside is added to the copper, hops are added, and the main mash is lautered and also added to the copper. This wort is then slowly brought to a boil.

In the late 19th century, this method was considered to be completely outdated, and only practiced in Augsburg. It was hard to scale it up to larger amounts, and suffered greatly from issues of the mash getting sour during the whole process. Beer made using it was described to be very full-bodied and less perishable than other Bavarian beers.

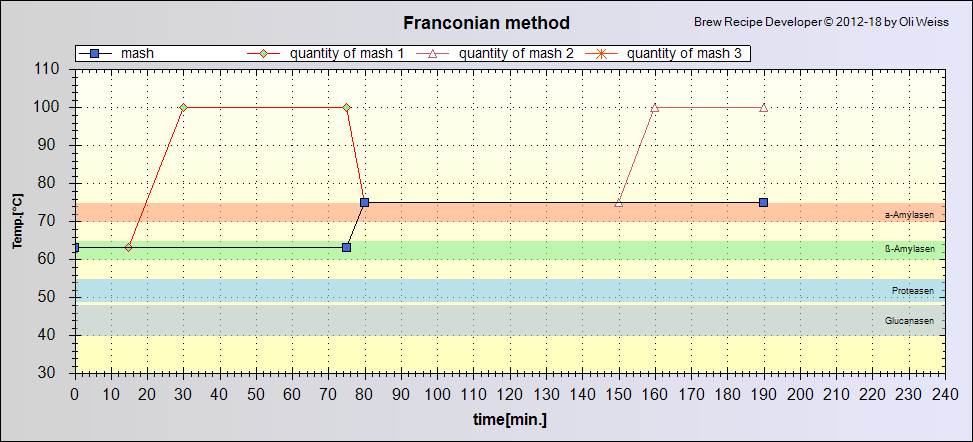

Franconian Method

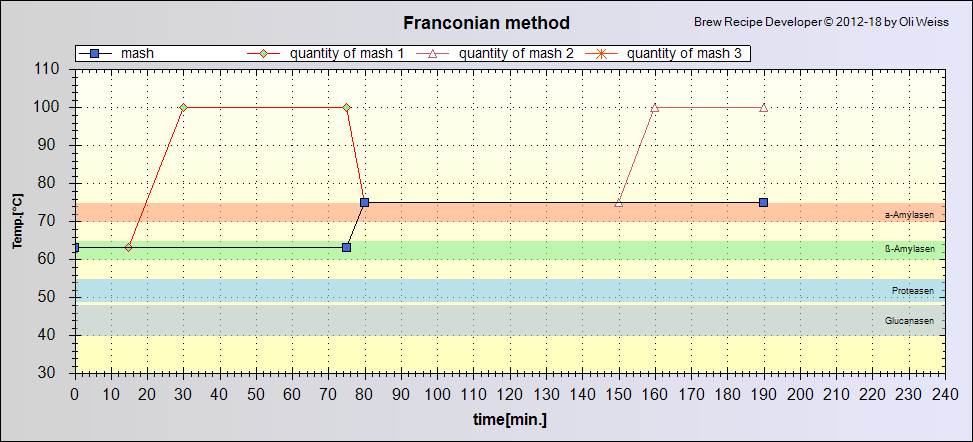

The Franconian method, as described by Franz Cassian, is a single step decoction mash. The malt to wort ratio (by weight) is 1:6 to 1:7. Hot water of 80 to 85 °C is thoroughly mixed with the malt to reach about 60 to 65 °C and then rested until all hard matter has sunk to the bottom of the mash tun. Then, all the wort is drawn off and brought to a boil. All hot break is thoroughly removed, and the wort is boiled for 45 minutes. After that, it is mixed back into the mash to bring it up to 75 °C, and then thoroughly stirred and rested for an hour to continue conversion. Then a small amount of wort, about one tenth of the whole volume, is drawn off and used to boil the hops for about 30 minutes, then the rest of the wort is drawn off, added to the wort and hops, and boiled even longer (the author doesn’t specify how long, though).

Both beers brewed after the Augsburg and the Franconian method are sparged, but the resulting second runnings aren’t added to the first runnings, but rather made into a small beer called “Hansle” (if you’ve read my book, other sources also call this “Heinzele”).

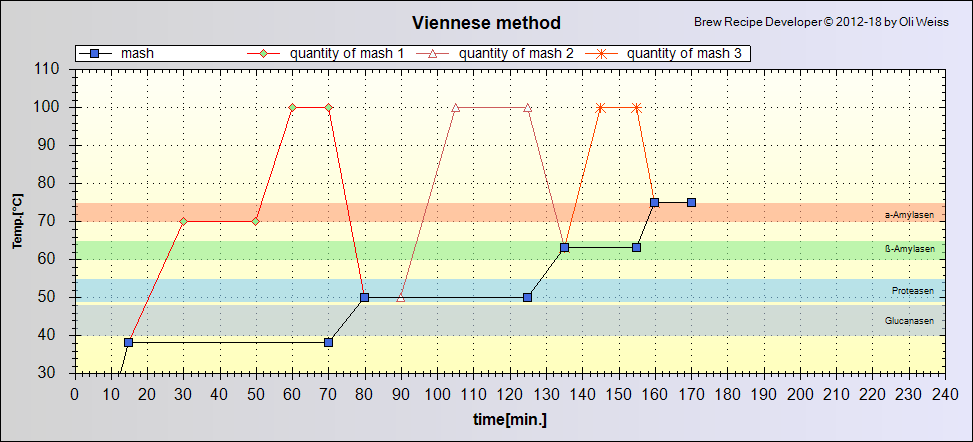

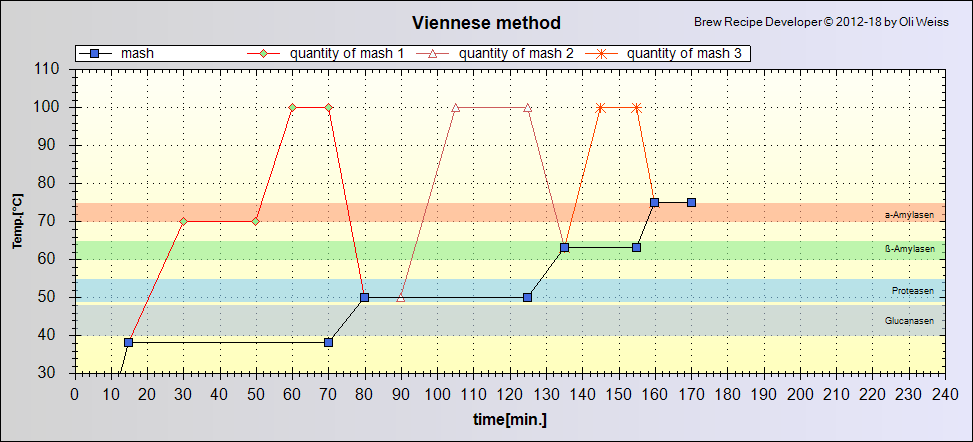

Viennese Method

According to the author, this method may actually be used to produce more beer than with the Munich method, as it has been in use not only in Austria and Germany, but also in France, Norway, Russia, as well as breweries in North and South America. The method is described in very specific numbers:

To produce 100 liters of beer, 20 to 22 kg of malt are used. The total water amount is 200 liters, split up into the mash water (125 to 166 liters) and the sparge water (34 to 75 liters).

To malt is doughed in with 2/3 of the cold mash water, while 1/3 of the mash water is brought to a boil. It is stirred until it is completely smooth, and only then the boiling water is added to bring the mash to a temperature of 36 to 38 °C. The rest of the mash is done in a triple decoction fashion, with two thick decoctions and a thin decoction.

The first decoction is heated up, but not immediately brought to a boil: instead, it is rested at 70 to 75 °C for 10 to 35 minutes. After that, it is quickly brought to a boil, and boiled for 5 to 15 minutes. The boiling mash is then mixed back while thoroughly stirring to bring it to a temperature of 45 to 50 °C. After a rest of a few minutes, another third of the mash, again a thick mash, is drawn off and boiled for 20 to 50 minutes. It is then again mixed back. Unfortunately, the author doesn’t mention the expected temperature, but we can guess it to be in the range of 60 to 65 °C. For the final decoction, a larger amount of the whole mash, 40 to 50 %, is drawn off and brought to a boil so that the protein coagulates and the hot break settles. It is then mixed back into the main mash which should then have a temperature of about 75 °C. After some more stirring, the mash process is considered finished.

The mash is then lautered and sparged, and the wort is boiled with the hops. The stronger the beer, the more hops are used. Unfortunately, it doesn’t provide any specific hopping rates. Original gravities are mentioned, though: lager beers are generally at around 13 °P, while low-gravity draught beers are at 10 °P.

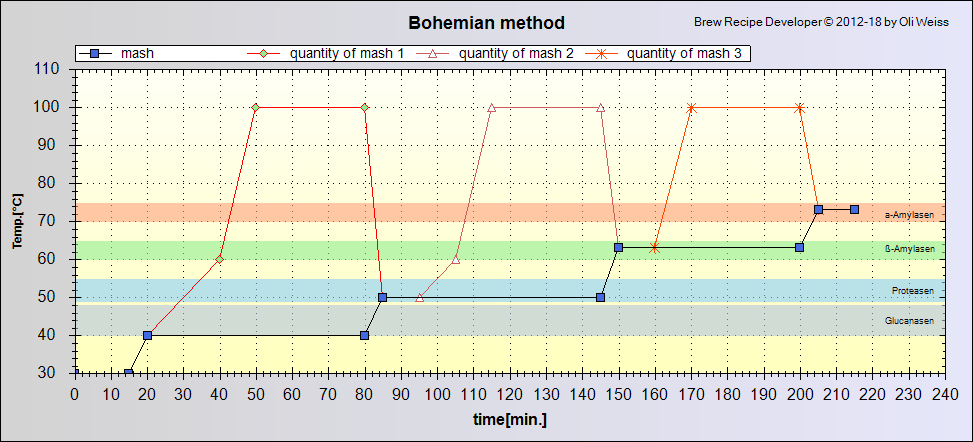

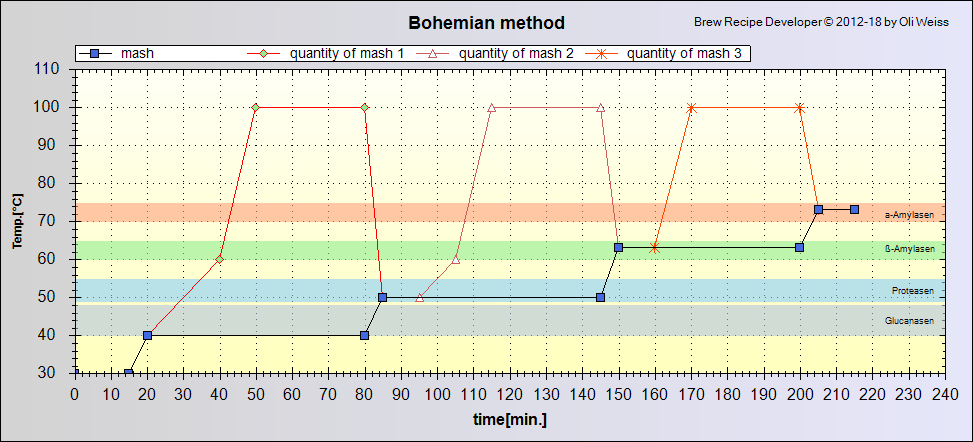

Bohemian Method

The Bohemian beers at that time are characterized as less malty, but rather more hop-aromatic. With every 100 kg of malt, 700 liters of water were used: 562 liters in the mash, 188 for sparging. 435 liters of water are used for doughing in at a temperature of 40 °C in winter, or 30 °C in summer. After doughing in is completed, 108 liters of boiling water are added to raise temperature. After a few minutes of rest, about one quarter of the thick mash are removed and very slowly heated up to 55 to 60 °C so that the enzymes can convert starches into sugar. After that, the decoction is brought to a boil, while the hot break gets skimmed. After 30 minutes of mashing, it is mixed back into the main mash, and stirred thoroughly to ensure a consistent temperature throughout the mash. After that, a second and third decoction are drawn and conducted exactly like the first thick decoction. After the third decoction has been mixed back, the overall temperature of the mash should be at 70 to 75 °C, and the mash is rested.

Wort is then drawn off until it is clear. The turbid part of the wort is boiled together with about 19 liters of water for a few minutes, and poured back into the mash. The mash is then moved to the lauter tan, and lautered and sparged with the sparge water that was set aside. The resulting wort is boiled with relatively large amounts of hops. Some of the hops are kept back and only added at the end of the boil to increase the amount of volatile hop aromas. This is what the author considered to be very specific for Bohemian beers and what gives them their typical hoppy aroma and flavour.

Discussion

While I’ve been working with lots of different sources when I was writing my book about historic German and Austrian beers, finding such a detailed description and comparison of various types of decoction mashing was quite refreshing. The Old Bavarian method is closest to what I’ve seen in plenty of other sources. I would describe it as the most classic method, pretty much fully based on manual labour, and done with an approach that employs volume measurements so that when done properly, no temperature measurements would be necessary. The ratio of malt to water is crazy high, though. For decoction brewing, today’s literature recommends ratios of 1:4 to 1:5. The text is not totally clear in all details, and might mean the total amount of water needed for the brew, i.e. including sparge water.

The Augsburg method, “Satz brauen” is truly odd. I’ve actually seen several different ways of how this is done, and the description as summarized above is actually the clearest one I’ve seen so far. It is possible to see why this method works and how it gets all starch converted, but it seems horribly inefficient, even in comparison to classic decoction mashing.

The Franconian method is closest to modern brewing. Any lower temperatures are skipped, and the main temperature is right at saccharification temperature. Other descriptions of the method that I’ve read don’t even employ a final thin decoction, but this might probably just be a local historic Bamberg variation.

The Viennese method on the other hand can be considered to be very modern: the specific method of resting the first decoction at about 70 °C for a while to let starches convert before the diastatic power is destroyed in the boil is a technique that even modern literature recommends, e.g. Narziß, though his recommended temperature is closer to 65 °C. And that’s what differentiates it from the classic Bavarian method: while it follows the same general pattern, it is more intricate, more detailed, more informed. It is built on top of the information that enzymes (though the book only says “diastase” without knowing what exactly enzymes are) break down starches to sugars at certain temperatures, and in the Viennese method, this is used to maximize fermentability of the wort. It is what I would call a modern method, this modernity would also be a good explanation for its success that is indicated by the author’s comment how internationally widespread the Viennese method has become.

The Bohemian method does seem a little bit more rustic, and differentiates itself by only using thick decoctions. It already builds upon the knowledge that starch conversion happens at certain temperatures, and leverages this knowledge to facilitate conversion when heating up individual decoctions. The specific mention of certain amounts of water does show that this has been thought through more and indicates that it closely follows a tried and tested recipe.

While not strictly related to the mash, the author discusses what distinguished Bohemian beers from other lager beers: the pale colour as well as the unique hopping method. I am not surprised that the author points out the use of late hopping techniques to introduce a brighter and more intense hop aroma. While we nowadays know that it’s the way of producing hop-aromatic beers, it is not a technique commonly seen in old brewing literature, where hops were only added for their preservative qualities as well as their bitterness.

All in all, this historic comparison of various mashing techniques from Bavaria, Bohemia and Austria was a great find. It gives a good insight into the shift from brewing as a craft involving manual labour (Old Bavarian method) to the industrialization of beer production supported by automation (New Munich method) and scientific methods (Viennese method). It also gives a good explanation what made Bohemian beer so unique and special in the late 19th century, which was also a reason why pale lager beers became the most widespread and successful type of beer in the world. And last but not least, it is also a good lesson for homebrewers how the decoction mashing process can be varied, in a form that’s even usable on a relatively small scale.

If you’re a homebrewer and you’ve never done a decoction: try it out. It may seem scary, but after brewing several beers with decoction mashing, I can safely say that it’s really hard to screw things up if you just follow the principle of doughing in, heating it up to about 40 °C, and then repeatedly taking out roughly a third of the mash, boiling it, and mixing it back. The mash goes through saccharification temperatures multiple times, and especially with enzyme-rich, “hot” malt that we have available nowadays, most of the conversion happens fast. I am a proponent of decoction mashing, because conceptually, it is really hard to screw up.