Okay, this is slightly random. Dortmunder Adambier is a beer style I never really looked into, and when I wrote my book Historic German and Austrian Beers for the Home Brewer, I didn’t really come across anything useful that resembled a recipe.

Earlier this week, I was contacted by homebrewer Jesper Hjortshøj who asked me whether I had any more information about how to brew this beer style. I admitted that I didn’t know anything, but it got me started to look into it how much I could find out. And quite quickly, I actually came across a description that was sufficient enough to derive a recipe from it.

The August 1869 issue of the Der Bierbrauer contains a whole article about the beer style with lots of information and details.

Dortmunder Adambier, apparently often also just called “Adam”, was a very strong dark wheat beer, often aged for years, and thus very clear, with a dark-red-brown colour. The malt made to brew it was kilned to only a pale colour, and no additional dark malts were used, so any colour of the beer came from “browned proteins”, as the article says it, basically from the long, intense boil the wort undergoes.

When Adambier was poured, it poured like oil, but without any foam, and had a sweet taste and vinous taste to it. It was brewed from either wheat or barley or a mix of both, but Adambier brewed from wheat was more full-bodied and tartaric, and thus preferred.

A very basic chemical analysis indicates that it was a very strong beer with 8.54% alcohol by weight (or 10.73% alcohol by volume), 21% residual extract by weight, 16.7°P apparent extract as measured on the saccharometer, and an attenuation of just 52.1%.

We also get more hints about the strength: one example that was analysed had an original gravity of 34.9°P. But there’s another hint: it says that in order to brew 20 Ohm (a local pre-metric volume measurement, I assumed the Brunswick Ohm of 144.8 liters) of Adambier, the same amount of malt is needed as for brewing 50 Ohm Bavarian beer. Assuming an OG of 12 to 13°P for Bavarian beer at the time, that means that Adambier brewed that way would have roughly have an OG of 30 to 32.5°P. Slightly lower than the analysed beer, but still roughly a similar strength.

We also learn about the hopping: for every Ohm of beer, 1 Pfund (500g) of “fine Bavarian” hops were used (later in the text, it even talks about 2 Pfund per Ohm). That converts to 3.45 g/l of hops, or if you use double the amount of hops, 6.9 g/l.

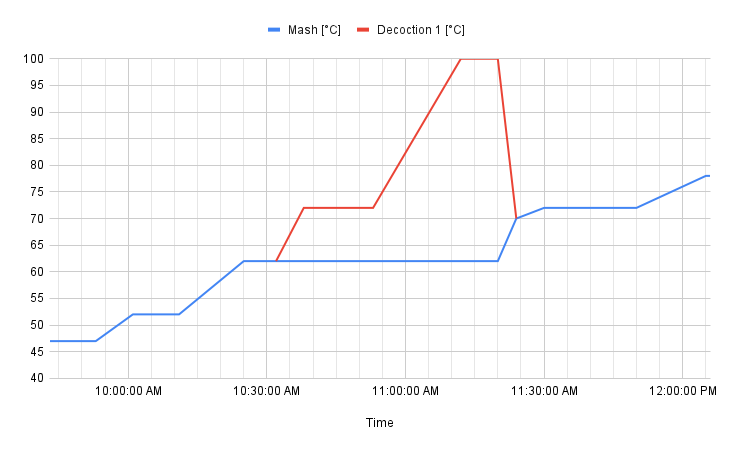

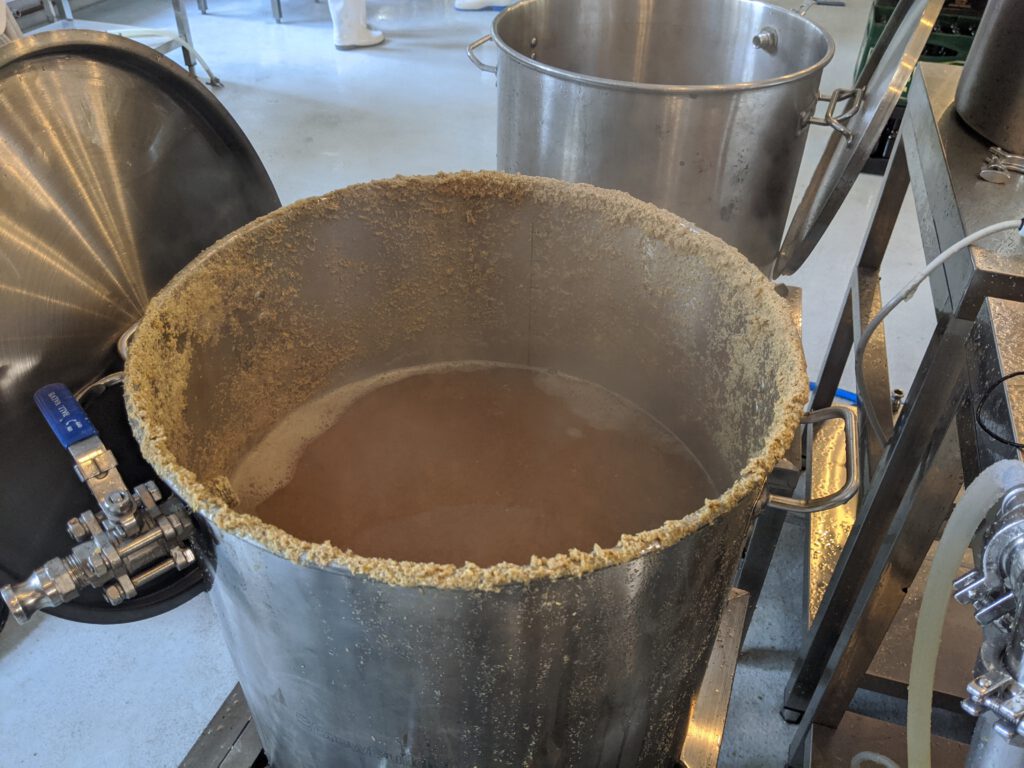

In 1869, the brewing this beer style was apparently already partially modernised, and it is implied that Bavarian triple decoction mashing was employed. But the old way of mashing it is already described, and it is wonky: the grist was doughed in in a kettle (the amount of liquor or the temperature of it isn’t documented), then left to rest, until it was brought to a boil. It takes 5 hours to bring the whole mash to a boil, during which probably the mash fully converted.

After the boil, the mash was moved to the mash tun, left to rest for 2 hours, and then wort was drawn off. At the same time, water was heated up for a second mash to draw off even more wort. Both worts were added to the kettle, hops were added, and the wort was boiled vigorously enough to effect good evaporation up to the desired strength.

The wort was then chilled to 10°C, and yeast was added at a pitch rate of 345 ml of yeast slurry per hectoliter. Primary fermentation took about 4 to 5 weeks. It was then filled into 10 Ohm casks, and the bunghole was kept open until the beer stopped ejecting yeast. It was then loosely bunged and aged for 2.5 to 3 years.

If I was to brew such a beer at home, I would approach it like this: since this requires producing such a strong wort, I would only brew half the amount of what I’d brew normally, let’s say 10 liters. I’d dough in my ingredients, Pilsner malt and pale wheat malt (the text says that pale malt was used, after all) with the same amount of liquor that I’d normally use for a 20 liter brew.

To make life slightly easier, I would probably just do a single-step infusion mash at 68°C or similar, or at most go for a double decoction, because I think most of the character of the beer will come from the long boil anyway, lauter, and then just go for a very long boil with 69 g of Hallertauer hops added to the first wort until I got the volume down to about 10 liters or the desired OG of somewhere between 30 and 35°P.

I would then chill down the wort, pitch whatever top-fermenting yeast I have on hand, and then just let it go. For sour beers, I have a dedicated fermenter that is contaminated, so any wort going into it probably gets infected with lacto and/or brett. Jesper said that when he brews his Adambier, he intends to pitch the dregs of a Schneeeule Berliner Weisse for just a small amount of lacto and brett, which is actually similar to my approach for the Old Ale that has been maturing for almost a year, where I simply pitched the dregs of two Gueuze bottles for secondary fermentation.

I hope that should give everyone who wants to brew a historically fairly accurate Adambier a good idea how to approach it and how to formulate a recipe for it. And thanks to Jesper for making me look more closely into the beer style!