On my recent trip to Kraków, I also spent a few hours at the National Archives to Kraków in an attempt to research two beer/brewing-related topics I’m interested in.

The way the National Archives in Poland work is that they’re decentralised, and archive material is stored geographically close to what it relates to, so if you’re interested in anything relating to Kraków and surroundings, the branch in Kraków is the one to go to.

I struggled a bit initially to understand the overall procedure, so here’s my attempt to document it if anybody else also wants to look up any documents from that archive.

- you search the archive for what you want to look up using this search form.

- If a document exists in digitised form, you can just read it online.

- If a document isn’t digitised yet, you can order it to view in the reading room of the respective archive. For that, you need to write down the archival group (collection) and the archival unit reference number. In this example, the collection would be Akta miasta Krakowa and the reference number would be 29/33/0/3.2.3/Kr 8243.

- For every reference number, fill out this form separately.

- Once the documents have been retrieved and are ready to be viewed, they will be reserved for 10 working days at the archive under your name, and you will receive a confirmation email that they’re available.

- Once you have that confirmation, you can book a time slot at the reading room. Don’t be worried if you only see one or two time slots available. These are just the morning and/or afternoon opening times. You don’t have to be exactly on time, and (at least from what I understood), your table will be available to you the whole morning or afternoon.

And that’s it. In the grand scheme, it’s not that hard, the overall process is just not well-documented yet in English and certain details, like how long will documents be kept for viewing, weren’t clear to me until I received the confirmation email. So always make sure to book your material far enough in advance, but not too far.

Now let’s talk about the archival material itself that I wanted to take a look at: a big reason for me to visit was to find out more about the historic Goldfinger brewery in Kraków. I previously did a little bit of research into Markus Goldfinger through online archives, mostly the Austrian newspaper archives. For more about that, please check out my article about the modern Goldfinger Brewery in Downers Grove, Illinois that I visited in June 2024.

Besides that, I also wanted to see what material there is relating to Johann Götz, the founder of Okocim brewery, as he not only operated his main brewery in Okocim, but also owned and operated a second brewery in Kraków.

Let me just say, my search regarding Johann Götz and Okocim was much more successful than the one regarding Markus Goldfinger and his brewery. There wasn’t much I could find about Goldfinger in the first place, and of two bundles of documents that I ordered, only one was made available to me. What I did get to view was a big bunch of correspondence between members of the Goldfinger family and the magistrate (think of it as the municipal office), most of them stamped with Austrian revenue stamps of 50 Kreuzer each (value nowadays would be roughly €8.50).

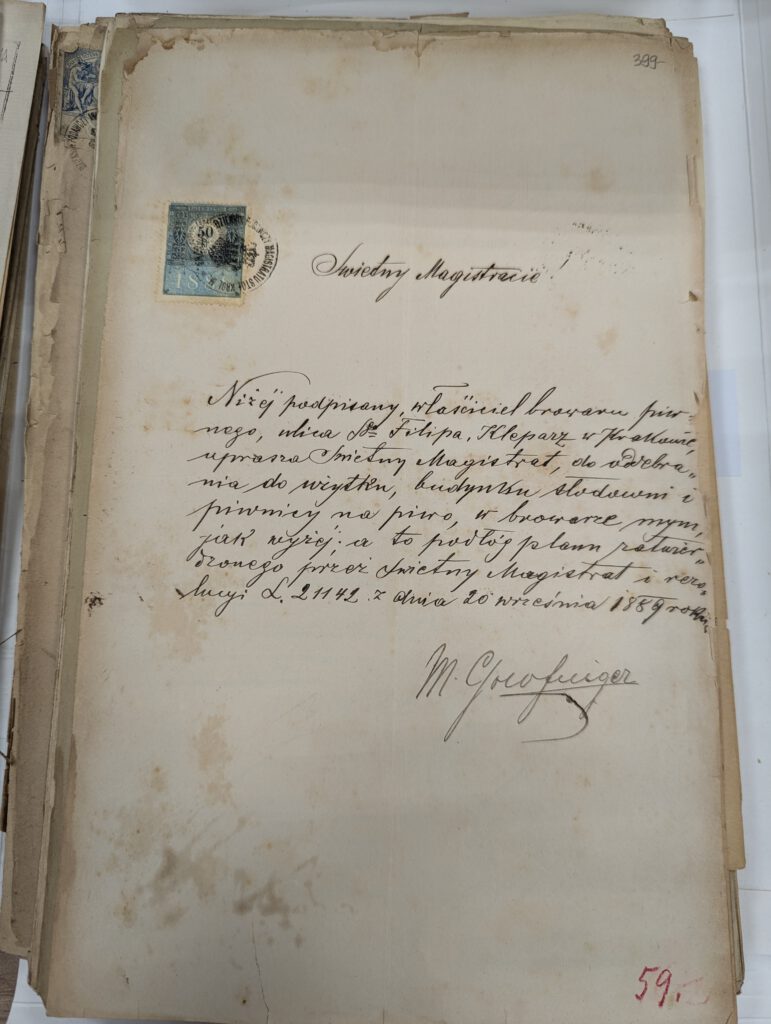

There was one letter that caught my eye, though:

What I could identify was the word “piwo” in the fifth row of the main text, which, upon closer inspection, turned out to be part of the phrase “piwnicy na piwo”, which translates to “beer cellar”.

Due to work, holidays and then a bit of illness, it took me a while to get it transcribed properly (I used Transkribus plus a lot of manual reading and trying to recognise individual letters because Transkribus’ result was far from perfect), but thanks to a good friend (thanks Filip!), I eventually managed to get it corrected and proof-read. The transcription goes like this:

Swietny Magistracie!

Niżej podpisany właściciel browaru piwnego, ulica św. Filipa, Kleparz w Krakowie uprasza Swietny Magistrat, do odebrania do użytku, budynku Słodowni i piwnicy na piwo w browarze mym jak wyżéj; a to podłóg planu zatwierdzonego przez Swietny Magistrat i rezolucyi L 21142 z dnia 20 września 1889 roku.

M. Goldfinger

Since I don’t speak a word of Polish (well, maybe one… piwo), I used DeepL to translate it for me, and this was the output:

Honourable Magistrate!

The undersigned owner of a beer brewery, St. Philip’s Street, Kleparz, Krakow, requests the Honorable Magistrate to put into use the Malt House and the beer cellar in my brewery as above; this according to the plan approved by the Honorable Magistrate and Resolution L 21142 of 20 September 1889.

M. Goldfinger

While the wording is a bit clunky (according to Filip, the language used in the Polish original is a bit dated), it’s basically a request from Markus Goldfinger to the magistrate for permission to start operating the malt house and the beer cellar.

So there’s a new mystery: why did Mr. Goldfinger require permission to operate a malt house and a beer cellar. Are these by any chance new ones that were built? The brewery was founded about 15 years prior, so the brewery presumably had a beer cellar and the means to malt barley by then (back then, a lot of breweries were still malting themselves).

Nevertheless, a very cool find, and it got me closer than ever before to be able to see and feel hand-written letters from Markus Goldfinger himself.

As for the history of Johann Götz and his breweries, I found a large amount of documents, photos and technical drawings (and interesting ones too!), so there is much more to unpack before I can publish a blog post about it.