Alistair Reece recently blogged about brewing communes in Bohemia during the 19th century. As we had a brief exchange about this topic, I thought it would be worth looking more closely into the history of Braucommune Freistadt, the last remaining brewing commune in Austria.

The history of the brewery in Freistadt is quite a fascinating one: officially founded in 1777 (we’ll get to that later), its company structure is a remnant of how old brewing rights used to be organized. As Alistair mentioned in his blog, another remnant is the Zoigl tradition in the Oberpfalz, but it has survived in a slightly different way.

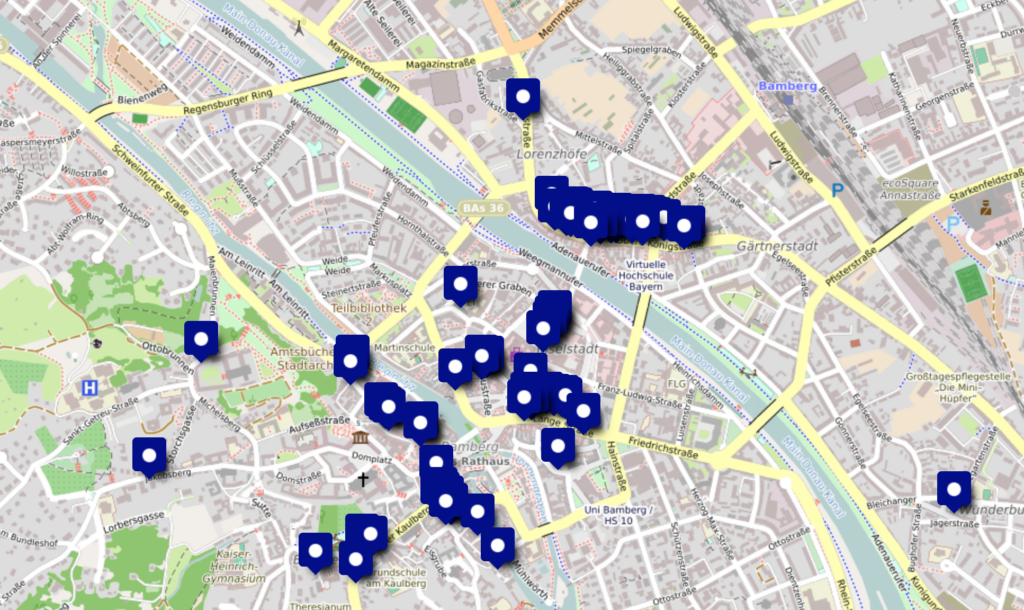

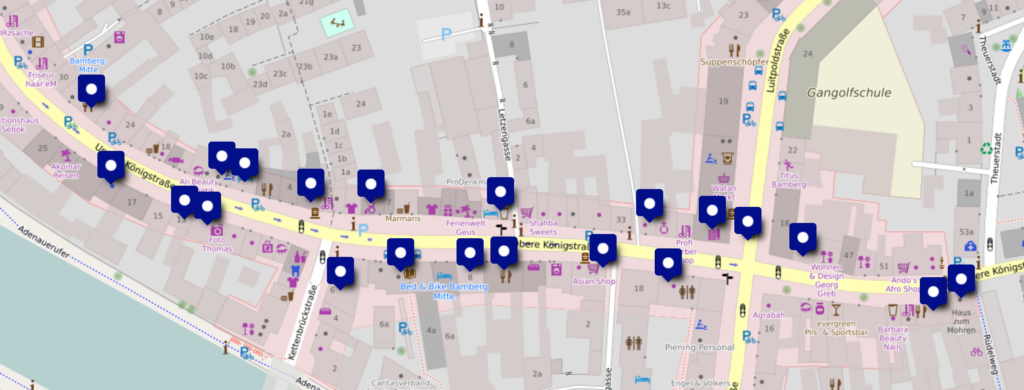

As someone who has been socialized as a beer drinker in Upper Austria, everyone just knew about Freistädter brewery and what makes them unique: the company is owned by the real estate owners of the Old Town of Freistadt (i.e. what’s within the city walls), company shares are tied to specific houses, not their owners, and the owners of these houses still have an “Eimerrecht” (lit. “bucket right”, where the Eimer, about 56 litres, was an old measure for liquids such as beer), which nowadays means that the brewery pays out dividends.

The city of Freistadt has had the so-called “mile right” since 1363, that forced everyone up to a mile (longer than a modern mile; the 17th century definition in Austria was roughly 7.58 km but it may have been even longer as the mile right apparently extended up to Kerschbaum which is more than 9 km away from Freistadt) to have to buy their wine, mead and beer from Freistadt, no brewing on site was allowed. This was a powerful privilege, and guaranteed the citizens of Freistadt income from their beer brewing.

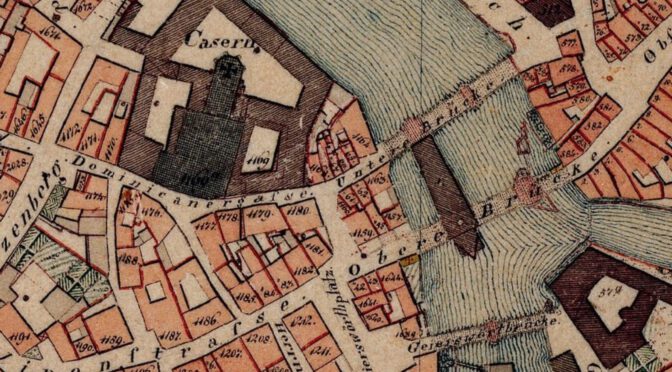

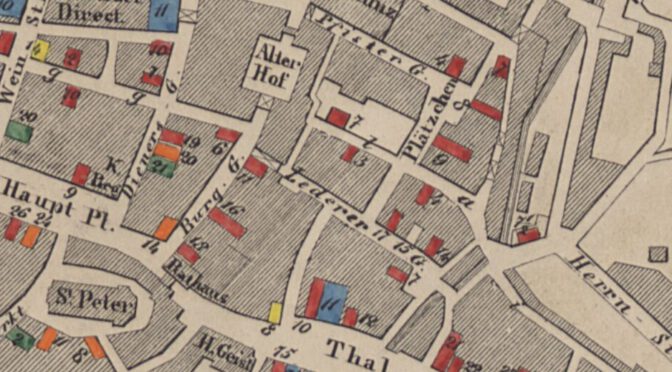

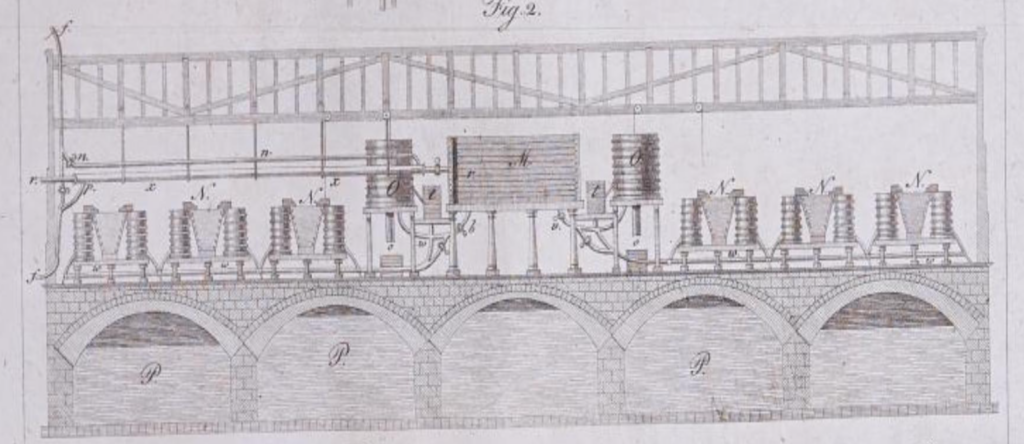

Speaking of the brewing itself, this was originally something that was done at home at the time. For practical reasons, the brewing was not necessarily done in the households, but in separate brew houses. In 1525, Freistadt had 12 dedicated brew houses, in 1637 still 5. One house was then set up as a dedicated white beer brew house (white beer was popular through the influence of Bohemian White Beer). From 1687 onwards, Freistadt only had two brew houses: the white brew house which was owned by the city and the brown brew house which was owned by the citizens. Every citizen had brewing rights, the amount of which was determined by the value of their house and noted in the city’s house registry.

Some houses were excluded from these brewing rights, either because they didn’t belong to citizens or because they were built much later (you couldn’t just buy yourself into it by building a new house within the city walls). Particular houses that were excluded were those owned by the church, which included one house (no. 11) which originally had brewing rights but was then bought by the church and donated to the Piarist religious order, thus losing that right, as well as the local school that was founded by the church. Houses owned by the city also didn’t have brewing rights for the brown brew house, which included the town hall, a tower of the city walls, the local city barracks, and the white brew house (well, it did have brewing rights, but they were separate from the citizens’ brewing rights); the same applied to houses owned by the state or nobility (e.g. the local salt authority building).

Before the new brew house was built, the brown brew house was also rented out, regularly for periods of 3 years. The tenants had to take on quite a bit of risk, they had to pay in a substantial deposit, and they had a number of responsibilities: the quality of the beer, they had to deliver Germ (baking yeast) to the local bakers (a strong indicator that the beer was top-fermented), they had to take care of selling the spent grains, they had to pay the brewer, the brewing workers, the coopers and the beer transporters. But they also had certain privileges: they were allowed to export beer on their own, and they were allowed to confiscate as contraband any beer or cider (Most) imported by innkeepers, of which they were allowed to keep 50%.

As for the ingredients, some of the barley was grown by the citizens themselves, while more barley was bought from local farmers around the city, and occasionally, when the local supply was used up, even from Bohemian cities such as Budweis/České Budějovice and Krumau/Český Krumlov with which Freistadt has had a close trade relationship. Hops were grown locally (Mühlviertel, the part of Upper Austria north of the river Danube, has historically been a minor hop growing region), but sometimes also brought in from as far as Saaz via Krumau traders.

The decision to build a new brewhouse was made for several reasons: the brown brew house was basically falling to bits and constantly needed repairs done, having an old brewery within the city walls always brought with it the danger of fire, the experience with renting it out hasn’t always been great and had caused some damages to the citizens in the past, and fear of competition (Bohemian beer from the North, beer from Linz from the South) and a possible loss of the exclusive “mile right” that required a consolidation and rationalization in the production of the local beer.

A precondition to build a new brewery was that the citizens had to buy the old white brew house including the brewing rights. One original idea was that that brew house would get modernized and the brown beer brewing would get moved there, but the alternative was to build an entirely new building outside the city walls. After some negotiations, the buying contract between the citizens and the city was finalized on December 31, 1770, when building works for a new brewery had already begun.

Building the brewery itself was a slow process, and it took 10 years until the brewery was completed. Where does the supposed founding date of 1777 come from then? That year was when the building works were the most active, and when most of the building was completed. The main gate of the brewery building bears the year 1777 because of it.

The old brew houses were emptied and equipment was moved over to the new brew house in 1780. Some of the old coppers were sold to the local copper smith to turn them into new coppers for the brewery. The white beer brew house was sold in 1781, and the buyer with his new house was admitted as a citizen of Freistadt, receiving the transferred brewing rights from the old brown beer brew house of 30 Eimer.

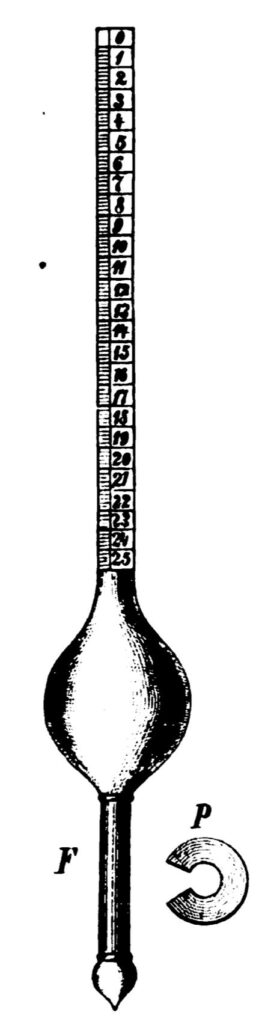

At what scale did this new brewery operate? For the early years, this is hard to tell, but we know from an 1886 ad that the brewery was selling a 48 hectolitre copper pan, an iron coolship of the same volume and a sparger “due to the conversion to machine operation”. From brewing statistics of the same time, we also know that the brewery was brewing about 10,000-11,000 hectolitres of beer a year, which pans out to 1 batch a day on 4 to 5 days a week. With that amount of brewing, they were considered a medium-sized brewery for Upper Austria. Other industrial breweries, like Dreher in Schwechat, brewed at an entirely different scale at the same time, around 450,000 hl per year. For Freistädter brewery, it was obviously good enough to satisfy the demand of the local market. A shift in production size seem to have happened in the 1890s, when the annual amount went from 11,150 hl in 1892 up to 19,861 hl in 1898. Up to 1930, this annual amount remained about the same (most likely interrupted by brewing restrictions during World War 1), at roughly 20,000 hl per year.

Ironically, the Braucommune in Freistadt was only added to the company registry at the commercial court in Linz in 1895. This registration clearly listed which house numbers were included as shareholders. It even very clearly says “Company owner is a society of the respective owners of the following houses located in Freistadt: 1, 2, 3, 4, […]”, cementing that the company ownership has been bound to the houses, not the citizens.

Nowadays, Freistädter brewery has the status of a local brewery serving the local market, brewing beer that generally has a good reputation. Distribution is limited, and within Austria, is mainly limited to Mühlviertel (i.e. Upper Austria north of the river Danube), a few major cities of Upper Austria including Linz, and then Vienna, Austria’s capital. As for the annual production volume, it has grown in recent years: for 2013, the brewery reported 65,000 hl per year, but by the end of 2018, more than 100,000 hl per year had been brewed.

Fun fact: thanks a former work colleague of mine who lives in Freistadt (though outside the city walls), I visited the brewery a few times in 2007/2008, for a monthly event called “Abpiff” (lit. blowing the final whistle) at the brewery: for a modest fee of €8, you would get a snack and about 2 hours time to pour (and drink!) as much beer as you wanted from gravity-dispensed serving casks (designated drivers were of course provided with non-alcoholic drinks). This continued until the final whistle was blown, and no more new serving casks were tapped. According to my former work colleague, this wasn’t just an event for the local beer lovers to get together, but also an opportunity for the brewery to try out new beers and one-offs. I loved the concept of it, and whenever The Event™ is over, I’d love to go back to it.

(As a source for this article, I mainly used the 1937 book 160 Jahre Braucommune Freistadt as well as various statistics from Gambrinus, the Austrian “brewing and hop newspaper”)