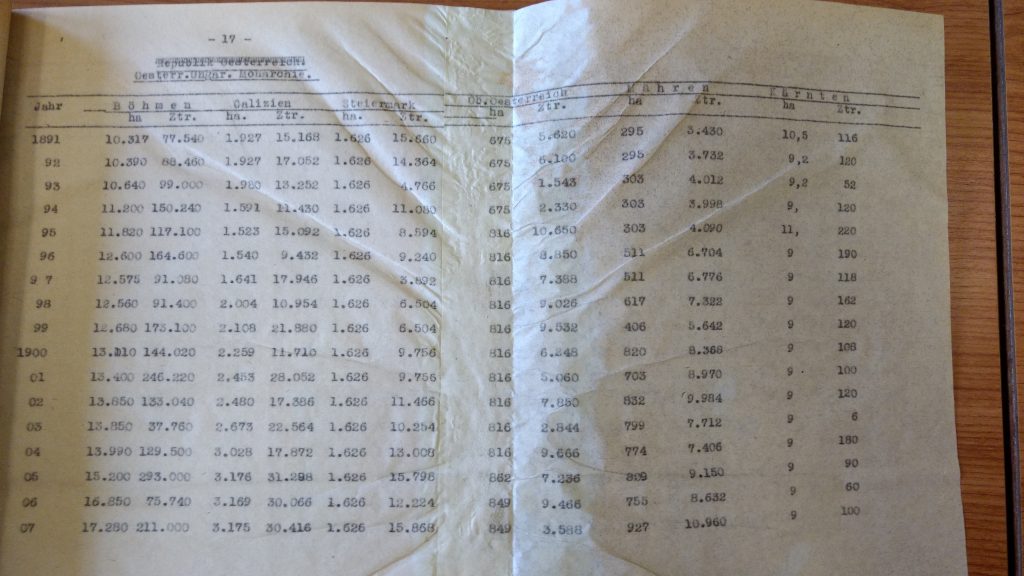

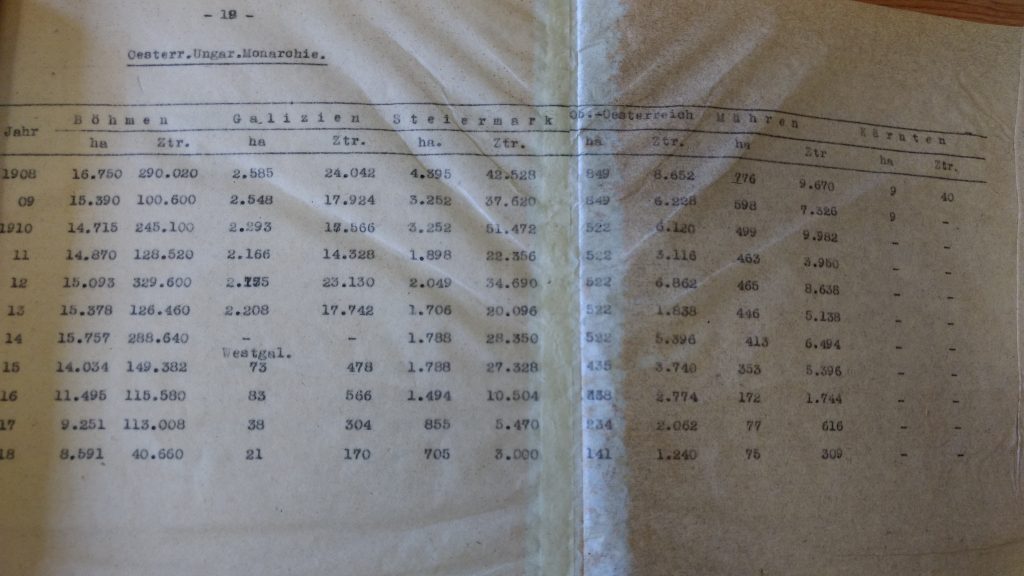

A few years back, I wrote about the demise of Upper Austrian hop growing. At the time, I was wondering what variety these local hops were. With the annexation of the Bohemian hop growing regions, the Upper Austrian hops all got uprooted, and only after World War 2, new hop of different varieties were planted. My research into Styrian hops about 3 weeks ago motivated me to also look into Upper Austrian hops in the same way, looking at what newspapers wrote about them.

In 1863, about 6000 Zentner of hops (1 Zentner = 100 kg) were grown in the Upper Austrian districts of Aigen, Haslach, Lembach, Neufelden and Rohrbach, all located in the Western part of Mühlviertel. That particular article is very insightful about what hops were grown: it mentions both “green” and “red” hops, referring to green bine and red bine hops. The quality of the green bine hops was allegedly very good, with a high amount of lupulin, and comparable to red bine hops from Auscha/Úštěk, while the Upper Autrian red bine hops were between Auscha/Úštěk red bine hops and green bine hops from. It apparently also preserved the beer very well until late into the season, the only complaint was that the prices paid for the hops were very low compared to the quality, especially in relation to the quality and prices paid for Auscha/Úštěk hops.

In an 1868 article, the same issue is being mentioned: Upper Austrian hop growers knew that their product had a good quality, but felt like they didn’t get nearly the right amount of money for it. This article defends the profitability of hop growing even at the prices at the time by calculating quite in detail how much you need to spend on growing hops, and how much revenue you’ll get out of it.

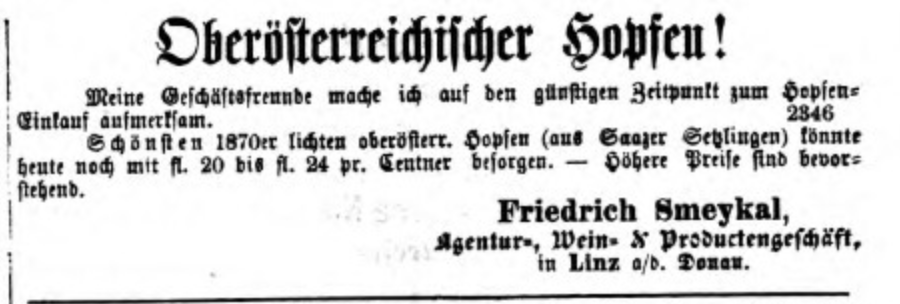

An 1871 ad gives us more insight into what variety at least some of these hops were. A trader from Linz advertised Upper Austrian hops from the 1870 harvest for 20-24 fl. per Zentner, and mentions that it was grown from Saazer seedlings. It is not clear whether this was the case for just this batch of hops, or whether this applied also to most if not all other hops grown in Upper Austria at the time.

The same trader, Friedrich Smeykal, reported in 1872 that he sold several hop bales of 1869 and 1870 harvest to a London hop trading house, which required him to prepare and package the hops in a particular way. To demonstrate this, he presented several bales at an exhibition of a local folk festival, as it could keep hops fresh and aromatic for several years. We unfortunately do not actually learn what that particular method was.

As mentioned earlier, the Upper Austrian hop grower were discontent with the prices that they were paid for their hops. An 1869 article claimed that hop growers were only paid 60 fl. for their hops, while at the same time, Upper Austrian hops were traded in Saaz for 90 to 100 fl. This is blamed specifically on Jewish hop traders, who the anonymous author accuses of arranging with each other, thus controlling the prices. The same author suggests that hop growers should form an association to centrally control the sales of Upper Austrian hops, thus having more leverage to dictate prices.

This article was immediately contradicted by an expert who specifically pointed out in a letter to the editor that on the day the article was published, Upper Austrian hops traded at 62 to 64 fl. in Nuremberg, while hops in Neufelden (where Upper Austrian hops were traded wholesale) were sold for up to 70 fl. The editors added a note to the letter, claiming that the author, although only anonymously signed as “an expert”, was a Jewish hop trader.

About a month later, another article was published in a different newspaper, denouncing the initial reports as wrong, not only correcting the wrong price information, but also scalding the use of defamatory, antisemitic language.

Similar to what I described in my previous article about Styrian hops and how they were bought up, repackaged, and resold as “Saazer” hops, reports about similar transactions also surfaced about Upper Austrian hops. Most of these reports are again specifically blaming Jewish hop traders, like this report from 1884 or this article from 1888. One article from 1885 even claims how this relabeling was allegedly discovered in one instance: an Upper Austrian brewer had purchased bales of Saazer hops, and when they opened one of them, they found a knife in it and were surprised to see the name of a local hop grower written on it.

In reality, the situation often wasn’t quite as bad. In January 1873, pretty much all Upper Austrian hops were already sold out in Nuremberg, showing that it must have been a popular product where demand must have outstripped supply. In January 1877, Upper Austrian hops even sold for significantly more (430-460 Mark) in Nuremberg than Saazer city hops (375 Mark), showing that the 1876 harvest must have been of even higher quality than the Saazer hops.

Not everybody only blamed Jewish hop traders, though. In one letter to the editor (published anonymously) from 1884, the anonymous author primarily blamed “Czechization” for local hops getting bought up for cheap by Bohemian hop traders, who then ship it back to Bohemia, “nationalize” it, rebrand it, and sell it back to Austrian brewers under different names instead of their actual geographic origin of Upper Austria resp. Mühlviertel.

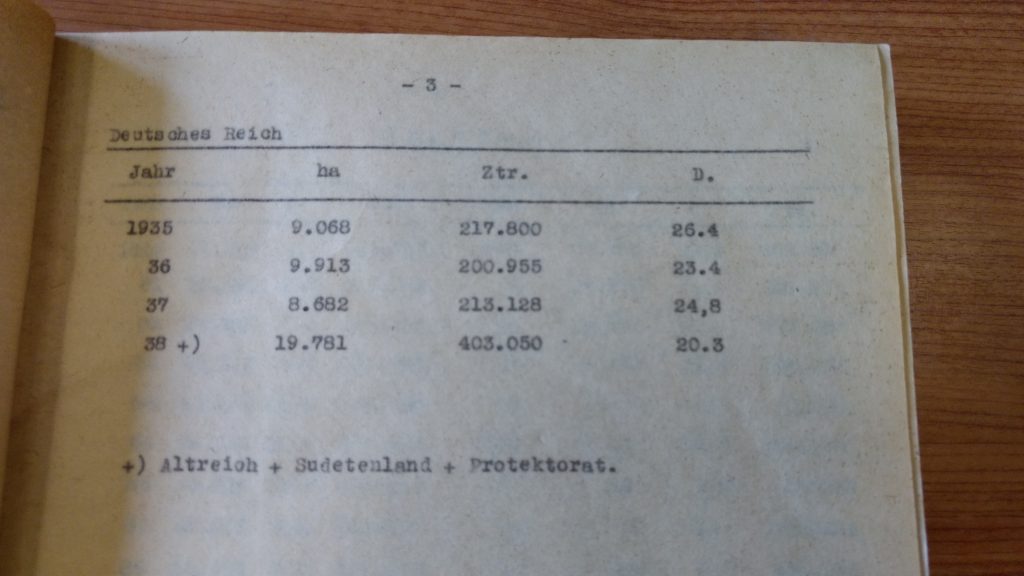

All in all, the amounts of hops grown in Upper Austria during the 19th and early 20th century were never particularly large, and with the dominance of Bohemian hops in the Austrian and European hop trade, they never established themselves as a “big name”, while still being able to compete with their relatively small amounts through quality.

Hop growing in Mühlviertel has fortunately been revived after World War 2, but the original hop varieties are nowhere to be found. Instead, hop growing restarted with the originally English variety Malling Mid-Season, grown in Austria simply as Malling, with more varieties that were added later on. Nowadays, you can even get Upper Austrian “Golding”, which is really Fuggles because it’s Styrian Goldings with an Upper Austrian terroir, as well as other varieties such as Aurora (also brought in from Slovenia), Perle, Tradition, Hersbrücker spät, Saphir, Spalter Select, Tettnanger, Magnum, Taurus, and even more craft-y “flavour hop” varieties such as Cascade, Comet and Sorachi Ace. And unlike back in the day, marketing and direct sales are nowadays also handled by the hop growers themselves. At less than €30 per kg for T90 pellets of last year’s harvest, I’m considering directly buying Malling hops or maybe Cascade hops for a future brew.