A few days ago, Jeff Alworth posted about the persistence of what he calls “romantic facts” around beer, i.e. “a story shot through with fascinating, possibly nostalgic details that turn out to be hogwash.“

I know about a few of those myself, such as the often found claim that the Habsburg Emperor of Mexico from 1864 until 1867, Maximilian I., supposedly brought Viennese brewers to the country who in turn established Vienna Lager in Mexico. This is hogwash because it matches nothing that we know about the actual history of beer and lager brewing in Mexico from closer to the time period, namely that Mexican brewing was a late 19th century reaction to US-American imported beer pushing into a market that was previously was very small and mainly served the European expat community in Mexico with lager beer imported from Europe.

But that’s not what I want to talk about today. One of my pet peeves of beer myths is the German Reinheitsgebot (purity law). I consider it to be mainly a marketing vehicle that is overloaded with myths and misinterpretations that ultimately are only there to help with marketing German beer, and there are many layers to it that I want to untangle.

The German Reinheitsgebot is a very recent invention. Germany has only had (mostly) unified beer legislation since 1906, and it’s mainly coming from the Southern German states of Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden pushing for it. To this day, the law is implemented ever so slightly differently for top-fermented beers in the south of Germany.

Even the term “Reinheitsgebot” is pretty recent: it is often claimed that the word was first used in parliament in 1918, but that might be a “romantic fact” in itself, as the first use of that word according to the Google Books Ngram Viewer was in 1904. The earliest one I could find was a 1909 Reichstag session report that specifically is in the context of beer and the unified beer legislation of 1906.

Prior to that, the term “Surrogatverbot“, meaning a ban on using surrogates for malt and hops, was commonly used, but even it was less strict than what you’d assume: in an 1870 book discussing beer taxation in the Kingdom of Bavaria, it specifically says that the use of hop surrogates is only banned for brown beers, and that “the use of hop surrogates in the production of white beer cannot be refused.“

A lot of the myth around the Reinheitsgebot also goes back to the Bavarian Reinheitsgebot of 1516, and I think here actually lies the crux of the problem: this piece of Bavarian legislation is misunderstood in its geopolitical context, in its importance and in its legal effectiveness.

Quite often, the 1516 Reinheitsgebot is also claimed to have been one of the earliest food safety laws due to a supposed (implied) ban on other ingredients, or that its supposed ban on brewing with wheat was meant to secure the availability of the grain for food. But the truth is that we do not know any of the intentions behind it. To claim a specific intent is purely speculative, and I’ve not seen a single historic source from which such a conclusion could be derived. In fact, concerns about grain shortages were managed differently, such as through requirements that white beer could only be brewed from either home-grown or imported wheat (e.g. Ducal mandate of 1567), or through temporary total brewing bans that included beer made from barley malt (e.g. brewing ban October 1571-1580).

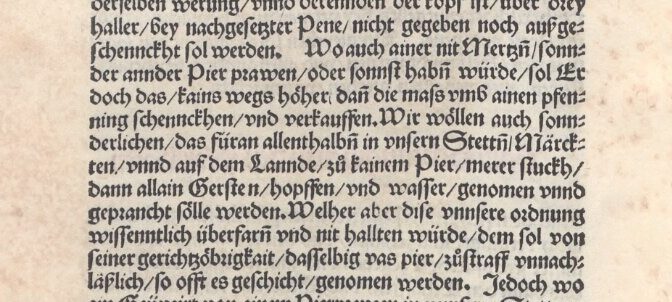

Also: The Reinheitsgebot of 1516 was not a revolutionary new piece of beer legislation. Many places across Bavaria and other parts of Germany had local legislation in place that regulated what ingredients were permitted or banned in beer. What the 1516 Reinheitsgebot did was that it harmonised the existing legislation for all those places that didn’t have a law in place. In particular, the 1516 Reinheitsgebot is virtually identical to an earlier decree from the Munich city council from 1447 that prescribed that only barley, hops and water could be used for brewing, which was later codified by Duke Albrecht IV. in 1487, which nowadays is also described as the Munich Reinheitsgebot of 1487, a marketing term used by the Munich brewing industry.

One problem with Bavaria was that during the Late Middle Ages, it was an absolute geopolitical mess. Bavaria started out as a stem duchy, one of the constituent duchies of the Kingdom of Germany in the 9th century. In later centuries, for various reasons, parts of Bavaria were split off, like Carinthia that was turned into a separate Duchy to reduce the power of the Bavarian Duke, or later the Duchy of Styria and the Marcha orientalis, Bavaria’s “Eastern realms”, the historic core of Austria. The House of Wittelsbach ruled remaining Bavaria after the deposition of Heinrich XII in 1180 until 1918.

But the Wittelsbacher had an issue with succession: they had no primogeniture in place like other noble houses, which meant that there was no customary preference for firstborns in succession. This led to various splits and subsequent mergers of land, and at times up to four partial Duchies of Bavaria existed, namely Bavaria-Landshut, Bavaria-Munich, Bavaria-Ingolstadt and Bavaria-Straubing between 1392 and 1429 (if you want to get down a bit of a rabbit hole: Bavaria-Straubing was actually part of Straubing-Holland from 1353 until 1429 which included parts of modern-day Netherlands and Belgium, including the cities of The Hague and Mons).

Anyway, all of that culminated in the Landshut War of Succession 1503-1505, followed by Bavarian reunification in 1506. Hundreds of years of divisions and mergers left behind a complex landscape of local laws that needed consolidation and harmonisation. This was accomplished through the Bayerische Landesordnung that was officially enacted on 23 April, 1516. Does that date sound familiar to you? That’s because it’s often quoted as the date from which the Bavarian Reinheitsgebot of 1516 was in effect.

What is usually left out is that the whole legal text contains a total of 160 pages regulating literally everything that needed regulating, like basics of the Bavarian legal system, its procedures, the punishment of crimes, the regulation of policing, Bavaria’s relations to the Holy Roman Empire, and regulations around topics such as blasphemy, public drunkenness, gambling, serving beer, wine and food in pubs and inns, beer brewing, establishing new brew houses and pubs, administration and accounting of church estates, dog ownership, animal farming, fishing (the book even contains prints of various types of fish as a reference for minimum fish sizes), milling, weights and measures, payment of day labourers, etc. etc. Of these 160 pages, how many are related to beer brewing? The section that contains the famous limitation on barley, hops and water as permitted brewing ingredients is less than one page in total, and it’s actually mostly about the pricing of beer.

German beer marketing often enough talks about how this was a complete ban on brewing with wheat. But that’s actually a misinterpretation of the scope of the law itself. An important legal principle at the time was that new laws did not overrule old laws. That meant that when you had the right or privilege to do something, it couldn’t just be taken away from you, and you couldn’t easily be banned from doing it by enacting a new law.

That meant that if you had the right to brew wheat beer before, you didn’t just lose that right. When the House of Degenberg received the “great freedom” to brew white beer in 1548, it was defined as “nobody but the House of Degenberg was allowed to brew and sell white beer between the Bohemian Forest and across the river Danube [meaning the right bank] across a wide area”. When the House of Schwarzenberg received a similar permit in 1586, that actually affected the Degenberger family’s exclusive rights and caused a brief conflict between both Houses.

Later Ducal mandates tried to control or limit the brewing of wheat beer, such as a temporary ban of white beer from 1566, because Duke Albrecht V. thought it wasted an incredible amount of wheat on a useless drink that neither nourished nor gave one strength.

In practice, there was also the question of enforcement, or really lack thereof: despite a ban to brew wheat beer for newly founded breweries since 1516, many of those popped up during the 16th century: in 1579, a Ducal commission found a total of 9 brew houses across the river Danube that brewed white beer (the House of Degenberg only owned and operated 3 brew houses, and it’s not clear whether their breweries were included in that report), and an additional 6 in the Bishopric of Passau, i.e. inside church territory and outside the control of the Bavarian Duke, but still in immediate vicinity. Then there breweries, often communal white brew houses that claimed customary brewing rights, like the one in Viechtach which claimed such rights even though it was only built in 1553, and even had the guts to complain about other breweries opening up in nearby town. Or the white beer brewery of Gossersdorf, which was only opened in 1600 as an entirely unlicensed operation by Georg Woerner, but instead of punishing the guy, the Bavarian Duke simply purchased the brewery in 1602. In 1599, a total of 20 white beer breweries in Lower Bavaria had been recorded by court chamber officials.

White beer brewing really only became restricted in Bavaria from 1602 onwards, but it was not because of a specific Bavarian law that regulated brewing. What happened in 1602 was that the House of Degenberg ended with the death of Hans Sigmund of Degenberg on 10 June, 1602, who had no male heirs. Duke Maximilian I. used this to establish a white beer monopoly for himself by effectively taking over the Degenberg operation and paying all the salaries, and purchasing the old brewing rights from the House of Schwarzenberg. But it also involved the legal question whether the Duke was even allowed to establish such a monopoly for himself. It took until 1607 to settle the legal disputes around that before the Emperor, who confirmed Maximilian’s sovereign right to establish such a white beer monopoly. Only then, the Duke was able to contractually oblige communal brew houses to share their profits with him or purchase communal or market town brew houses outright.

As is evident, Bavarian beer legislation in the 16th century did very little to actually ban brewing with wheat, for the simple fact that it could not touch old existing brewing rights, but also because it seemed mostly unenforced in Lower Bavaria, where white wheat beer had become popular, as long as the Degenberg and Schwarzenberg families’ brewing profits were not affected. The Bavarian Reinheitsgebot of 1516 had little to no effect on white beer brewing in Lower Bavaria. What actually changed the white beer brewing landscape was a Ducal monopoly for the Wittelsbach family starting in the early 17th century that had first to be confirmed by the Holy Roman Emperor.

And finally, the Bavarian Reinheitsgebot of 1516 does not have the historical continuity that it claims it does. A Ducal decree from 1551 permitted the use of coriander and bay leaves while specifically banning certain other herbs, while the Bavarian Code of Law from 1616 also allowed the use of salt, juniper berries and caraway seeds in reasonable amounts while other herbs or seeds like henbane were explicitly banned.

No law is put into effect without a perceived need for it, which means that between 1516 and 1551, there must have been enough brewers to use other ingredients outside the 1516 limitations that required an update or clarification to say that the practice of using coriander or bay leaves was actually fine, while other stuff was no good. The same goes for the time between 1551 and 1616, after which the law was updated to allow even more ingredients. So practically, whether enforced or not, the Reinheitsgebot of 1516 in that exact form was only a law for 35 years after which it was already changed. This is in stark contrast to the Bavarian beer marketing machinery that implies a certain historic continuity that just isn’t there.

And while modern German beer legislation is heavily influenced by the 19th century Bavarian position of a virtuous ingrediental minimalism, it was nothing the average German or even Bavarian beer consumer ever really cared about until fairly recently. Ironically, even regions of Bavaria like Franconia with their own rich brewing history that had nothing to do with the 1516 Reinheitsgebot and only became part of the Kingdom of Bavaria in the early 19th century nowadays claim the 16th century Reinheitsgebot as theirs. And it ultimately even affected mid-20th-century West German beer politics, as Robert Shea Terrell showed in his 2023 paper Entanglements of Scale: The Beer Purity Law from Bavarian Oddity to German Icon, 1906–1975.

To summarise, I think the Reinheitsgebot is misunderstood and its common interpretation as an early food safety law with a long, continuous history that strictly regulated brewing ingredients is one of these “romantic facts”. In reality, the 1516 Reinheitsgebot started out as just a tiny section in a big law book that was meant to harmonise and consolidate the existing laws of reunited Bavaria, and in its original form was only in effect for about 35 years. Due to the predominant legal principles at the time, it could not overrule older brewing rights, and was in practice at most loosely enforced when it came to the ban of brewing with wheat, including other subsequent Ducal bans later in the 16th century.

![Sign hewn into stone outside Fässla brewery, saying "inn and brewery zum Fäßchen, owner Seb[astian] Kalb"](https://dafteejit.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/MVIMG_20190723_171402-1-745x1024.jpg)