In the 19th and early 20th century, it was common to call beers in Germany and Austria by the place where they came from, a geographic indication if you will, such as Pilsner, Budweiser, or Münchner. Nowadays, this concept is applied to all other kinds of food and drink, and even has its own categories of protection on the EU level.

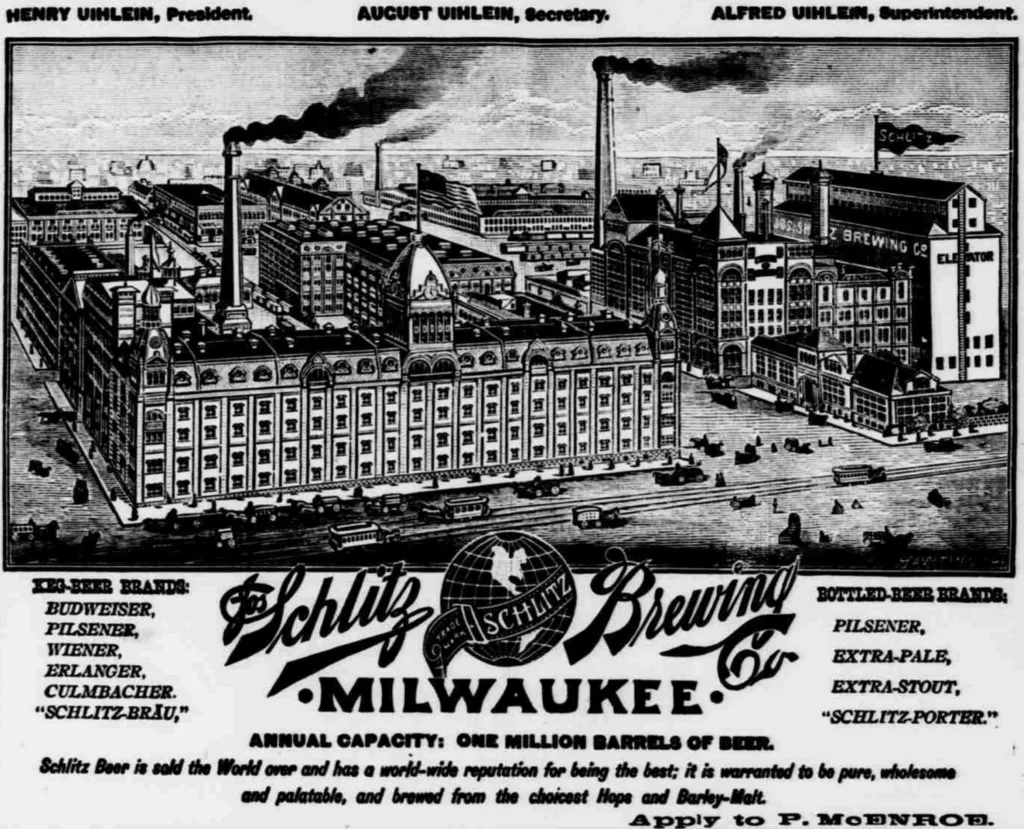

The success of specific beers of course often came with imitators. Some American breweries were good at marketing their locally brewed beers as all kinds of European beer types. One of my favourite examples is this Schlitz ad from 1891 that mentions Schlitz-brewed Budweiser, Pilsener, Wiener, Erlanger and Culmbacher, all referring to places in either Bohemia, Austria or Bavaria, all of them well-known for their beer at the time.

The case of Budweiser, which meant a century-long legal struggle between the breweries of Budweis/České Budějovice and Anheuser-Busch, is probably the best known one, but in the early 20th century, also some of the breweries of Pilsen/Plzeň weren’t super happy about the proliferation of the “Pilsner” resp. “Pilsener” name used for beers not from the Bohemian city of Pilsen/Plzeň.

(Ironically, nobody ever seemed to care about Anheuser-Busch stealing coopting another Bohemian place name well-known for its beer as a brand name, Michelob/Měcholupy)

In 1910, the breweries of Pilsen seem to have sued a number of German breweries, such as Pankow-based Engelhardt brewery, which were then initially banned from calling their beer “Engelhardt Pilsener” resp. “Engelhardt Export Pilsener”. The German court then found them to abuse the designation of origin of a foreign beer without clearly specifying that their beer wasn’t from Pilsen, but rather from Pankow just outside Berlin. This initial verdict is quite interesting, as it even specifically points out that a “light [i.e. pale], highly hopped, bottom-fermented bitter beer” didn’t necessarily need to be called a “Pilsner”, and specifically mentions Schultheiss Märzen as a counter-example of a beer with similar properties that makes no reference to the Bohemian city.

In December 1913 though, the Reichsgericht (Supreme court of the German Empire) in Leipzig passed a verdict that the term “Pilsener” had simply changed in meaning and couldn’t be seen as a pure geographic indication anymore, but rather as a statement of quality about the product, and that enforcing it as a geographic indication would be an interference into the “free development of business” by the court. The court also rejected any possible confusion of customers because of the price difference between “German Pilsener” and “real Pilsener”, and referred the case back to a lower court (this basically means that the Supreme court told the lower court what the correct legal opinion was meant to be). The complaining parties, namely Bürgerliches Brauhaus Pilsen, 1. Pilsener Aktienbrauerei and Pilsener Genossenschaftsbrauerei, were presumably not happy about it.

Just earlier that year, they had also sued Geraer Aktienbrauerei in Timm near Gera, Radeberger Exportbierbrauerei and Böhmisches Brauhaus in Berlin to stop calling their beers Timmser Pilsner, Radeberg Pilsner, resp. Pilsator (a brand that Böhmisches Brauhaus had started using only in 1909). The courts in these cases argued slightly differently, namely that while “Pilsner” hadn’t entirely lost its geographic indication, the prefixes of respective place names “Timmser” resp. “Radeberger” made the origin clearer and demoted “Pilsner” to a generic product name. In the case of “Pilsator”, it also noted that the beer had always been used in connection with Böhmisches Brauhaus Berlin, thus always making clear where it had come from.

This was hardly surprising, because even the Austrian administrative court had ruled in 1910 that “Pilsator” was merely a fantasy name that obviously did not indicate a provenance from Pilsen.

Little fun fact: the brand name “Pilsator” was the outcome of a competition in 1909 by Böhmisches Brauhaus Berlin that had been advertised with the slogan “Thousand Mark for One Word”. Among many thousand submissions, the jury selected the brand “Pilsator”. As this brand had been submitted by 26 competitors, the winner had to be chosen through a lottery, in which Josef Seestaller from Munich was drawn as the official winner. The Pilsner Tagblatt reported on this with the sarcastic comment that now the Berlin-based brewery just needs to do one more thing: brew a real Pilsner. The Pilsator name continued as a beer type in East Germany’s TGL 7764 regulation, and is still used as a brand name, namely Pilsator Pilsner brewed by Frankfurter Brauhaus in Frankfurt/Oder.

Pilsner beer wasn’t the only concern of the Pilsen breweries, though. In 1911, they petitioned the Prague commodity exchange (Produktenbörse) to stop using the terms “Pilsner malt”, “Vienna malt” and “Munich malt” because German and American breweries using “Pilsner malt” could claim that they were making “Pilsner beer” and that they had to defend their geographic indication in German courts. At the time, the question was referred to the Viennese commodity exchange.

Trade publication Der Böhmische Bierbrauer discussed in April 1912 how the term “Bohemian malt” was really more appropriate as it had been in use in scientific and trade publications, while “Pilsner malt” was more of a marketing term by maltings at the time. They suggested to change the official terminology at the Prague commodity exchange from “Pilsner malt” to “malt of wort colour up to 0.25 cm2 ⅒ n iodine solution”, “Vienna malt” to “malt of wort colour up to 0.40 cm2 ⅒ n iodine solution” and “Munich malt” to “malt of wort colour over 0.40 cm2 ⅒ n iodine solution”.

The article relents that this won’t get the term “Pilsner malt” banned but it will simply not get used anymore in official commodity exchange documents. They still asked readers to use the term “Bohemian malt”, not “Pilsner malt”, “as nobody will gain anything from it.”

Just a few days later, Der Böhmische Bierbrauer published another update about this matter. A report of the commodity exchange came to the conclusion that the proposal was practically a failure as it would only be limited to official documents at the exchange. At the exchange itself, it would also affect the interests of trading maltings that have used that term in their trade for a while now. Abuses of geographic indication should be pursued in other ways, according to the exchange.

Assuming from the lack of further reports on the matter, that seems to have been the end of it with regards to malt, and since the terms “Pilsner malt”, “Vienna malt” and “Munich malt” are still common trade names in the 21st century, the maltings have definitely prevailed.