Whenever somebody asks me how I would brew a Bavarian Dunkel, I have to respond that I never actually brewed one on my own. Instead, I rather point to an authentic modern-ish recipe from a Bavarian brewery from the 1960s.

A few years ago, Urban Chestnut Brewery from St. Louis, MO posted a sheet from 1967 brewing records of Brauerei Erharting in Bavaria. Their brewmaster, Florian Kuplent, had originally apprenticed there, and most likely got his hands on these records that way.

The recipe is interesting because there are a lot of assumptions baked into it that you’d only know if you had an idea about Bavarian brewing. It also challenges conventional wisdom that Bavarian brewers would just brew their Dunkel from 100% Munich malt. At least in the 1960s, this was not true anymore for this recipe.

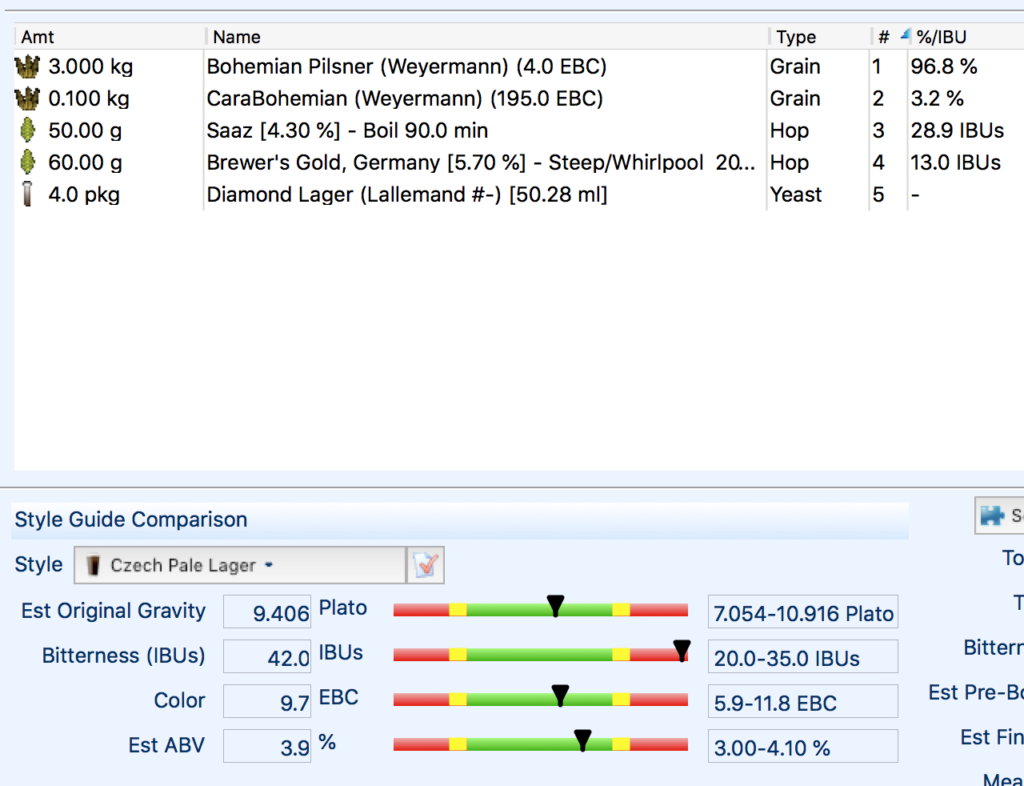

This recipe for Export Dunkel starts with the grist: it simply says 1350 kg of malt, of that 50 kg pale malt (lit. “Hellmalz”), 50 kg CaraMunich (originally CaraMünch, the German brand name), 10 kg roasted malt (Farbmalz in the original). What the recipe doesn’t say is the rest. The use of Munich malt (likely on the darker side) was simply implied from the type of beer that was being brewed. The pale malt was most likely a Pilsner malt. That way, we end up with a grist like that:

- 1240 kg Munich malt (91.9%)

- 50 kg Pilsner malt (3.7%)

- 50 kg CaraMunich malt (3.7%)

- 10 kg roasted malt, e.g. Carafa special II (0.7%)

Why the Pilsner malt? I can only speculate, but I assume that this might have been formulated under the assumption that the Munich malt had so little diastatic power that it would only self-convert and not fully convert the (enzymatically inactive) caramel and roasted malts.

The next part is the mash. It starts with doughing in the malt and letting it sit for 20 minutes at 35°C. This was typically done to ensure that all the malt was fully hydrated. Nowadays, this would be ensured through a pre-masher that would combine water and malt just before it goes into the mash tun.

Then, the mash was heated up to 52°C within 15 minutes. The mash tun must have been heatable.

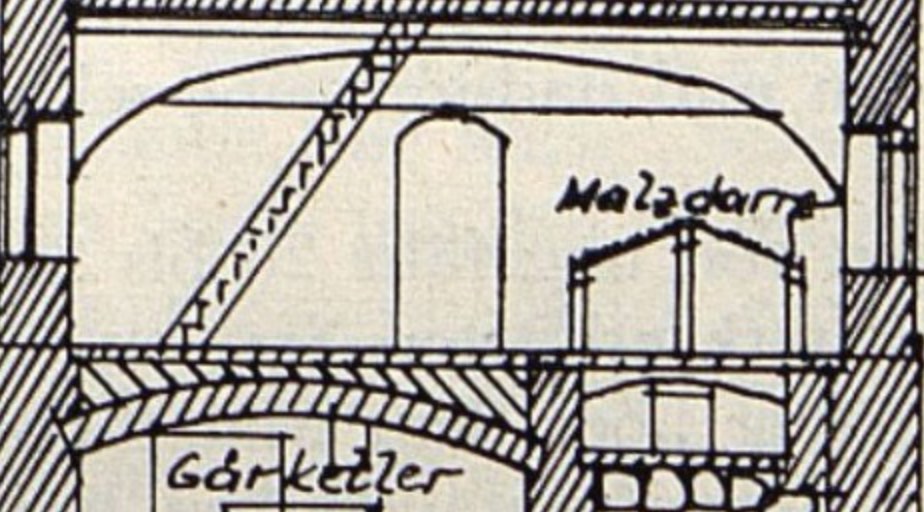

The recipe then further mentions to mashes. For the first mash, 22.5 hl of mash were pumped into the kettle while the stirrer was running. In the kettle, the mash the underwent a multi-step mash on its own: 10 minutes protein rest at 52°C while a bit of wort was drawn off (Malzauszug) and kept in the Grant, 10 minutes saccharification at 60°C, 10 minutes saccharification at 65°C, 70°C until iodine test was negative and the mash was fully converted (normally 20 to 25 minutes) and then 75°C for another 5 minutes.

This step mash prior to boiling the mash is done to maximize the use of the enzymes that will eventually be destroyed, and to convert as much starch as possible, so that the intense boil will only extract some more starches to be converted in the second mash.

Then the mash was brought to a boil, boiled for 35 minutes and then mixed back into the main mash which then reached a temperature of 65°C.

Then the second mash started: 23 to 23.5 hl of mash were again pumped into the kettle, rested for 10 minutes at 65°C, then again rested at 70°C until iodine test was negative, and then 10 minutes more at 75°C. It was then boiled for 25 minutes, and mixed back into the main mash to reach a temperature of 74°C.

The wort that was drawn off must have then been mixed back in, the recipe is not fully clear on this, though. I don’t know exactly why, but I assume that this was done to retain some amylase enzymes and ensure that some end up in the mash just before lautering to help convert any last few bits of starch (even though this is unlikely given how thorough the extraction must have been through 2 long decoction boils).

Then lauter and sparging happened to collect about 100 hl of sweet wort which was then boiled for 2.5 hours. The resulting amount of wort at the end would have been 78 to 79 hl with an OG of 12.7 to 12.8 °P.

The hopping schedule looked like this:

- beginning of the boil: 4 kg Hallertauer hops

- 1 hour after beginning of the boil: 4 kg Hallertauer hops

- 45 minutes before the wort is pumped off the kettle: 3 kg Spalter hops

The last one is particularly important: the timing does not depend on the end of the boil, but rather on when the wort is moved from the kettle to the chillers. None of the hop additions come with any indication of alpha acid content. There is one source though where we can get an estimation: international hop trader Barth Haas has its full range of historic hop reports online, both in German and English. The 1966-1967 report in English at least reports the “bitter value Wöllner” for some hops: 6.2 for Hallertauer hops and 6.6 for Spalter hops, both from the 1966 crop.

This “bitter value Wöllmer” was an early approach to estimate the bittering quality of hops. In particular, this value is calculate as alpha acid % + beta acid % / 9. For both Hallertauer and Spalter hops, we can assume that the alpha acid content is roughly the same as the beta acid content.

6.1 = x + x / 9 and solving for x gets us an alpha acid content of about 5.5% for Hallertauer hops.

6.6 = x + x / 9 and solving for x gets us an alpha acid content of about 5.9% for Spalter hops.

Bear in mind that these are just estimations, but should nevertheless give us a general idea about whether these were more high or low alpha acid for the variety.

And this is how you interpret a 1960s German recipe for Bavarian Dunkel.