By now, many of you have probably heard of the great news that Carlsberg Marston’s, who used to run the last remaining Burton Union brewing system, have handed over one set to Thornbridge Brewery in Bakewell, which will use it to ferment specialty beers. If not, Pete Brown will fill you in on some of the details.

As Pete Brown wrote in his blog post:

I’m sure there’ll be lots of hot takes on this.

So here is mine: Thornbridge should use their Burton Union to ferment a Bavarian Weissbier.

“But Burton Unions were built and used to ferment classic British beers, what’s got Bavarian Weissbier to do with it?” Glad you’re asking.

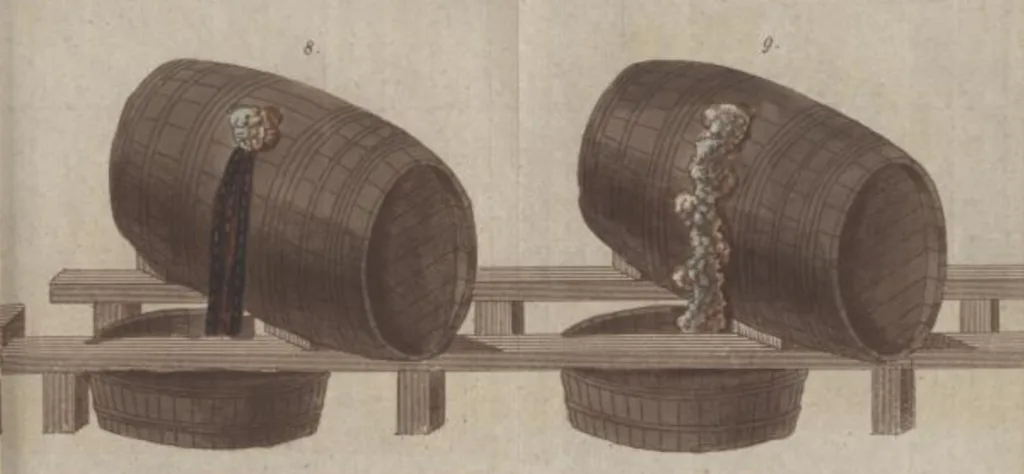

Let me start from the very beginning: in terms of historic fermenters, there are two big approaches: open fermenters and closed fermenters. The former are basically vats where the yeast is rising to the surface and can be skimmed off, while the latter are casks with a bunghole from which all the yeast (and some of the fermenting beer) is ejected.

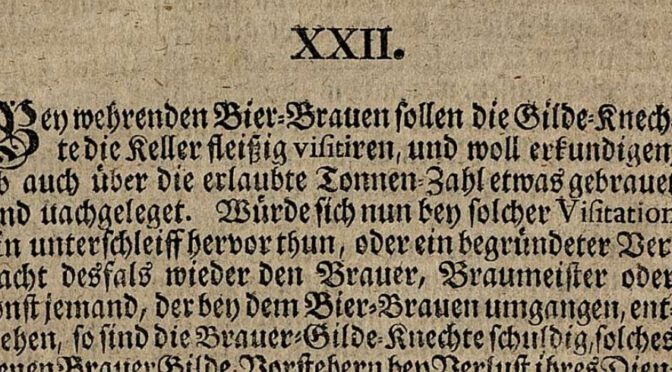

German brewers call these approaches Bottichgärung and Spundgärung. English brewing also employed both techniques, but interestingly, Bavarian brewers used to make a clearer distinction, where Bottichgärung was typically used for bottom-fermented beers, while Spundgärung was exclusively for top-fermented beers.

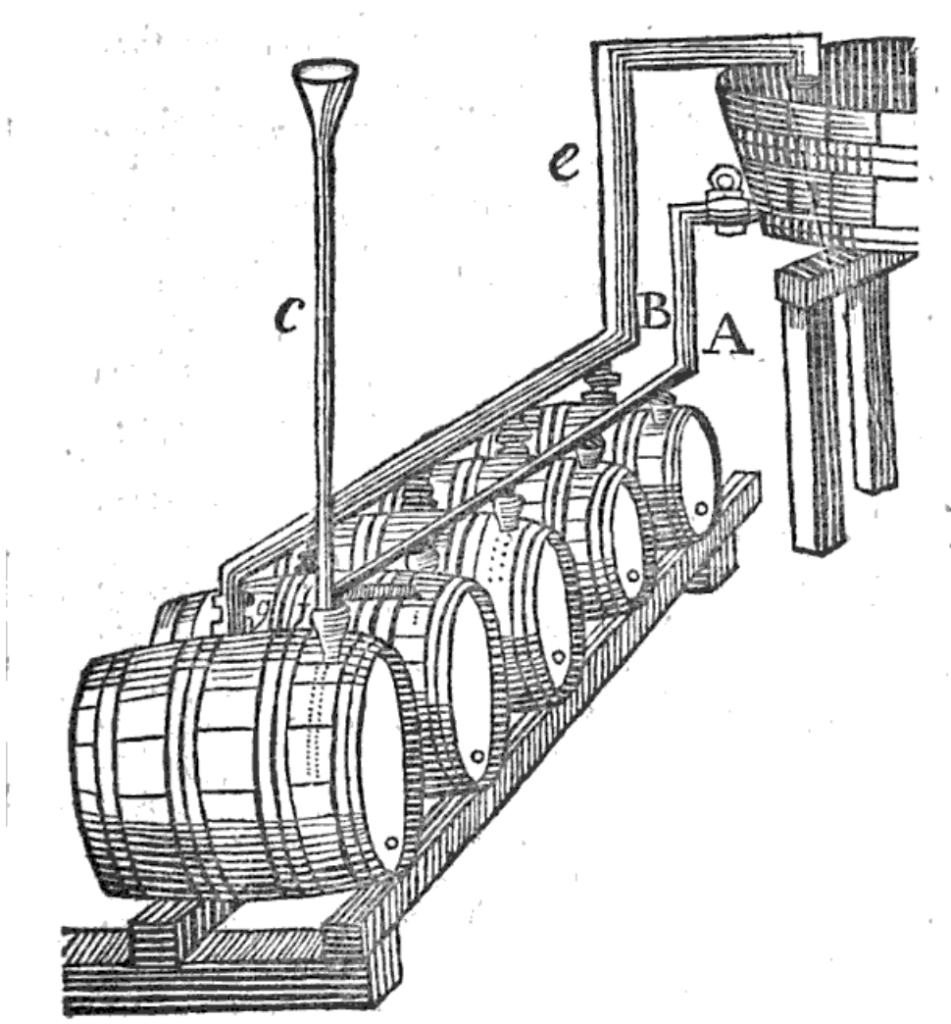

The most primitive way of Spundgärung went like this: the wort was added to a cask, filled pretty much to the top, and yeast was pitched. Any yeast that would otherwise rise to the top would get ejected through the cask’s bunghole and run off down the side of the cask, where it would get caught in a tray. Any beer also ejected with it would be used to top up the cask, until fermentation was finished.

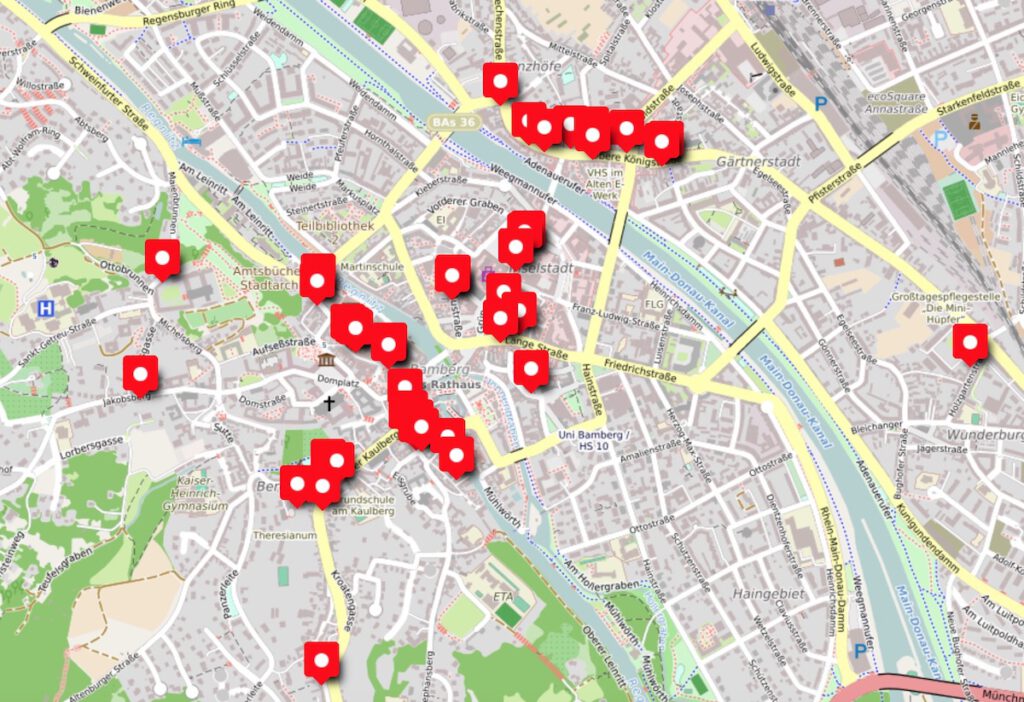

This is of course manual labour, and not the most hygienic, either. So is there a way to do this in a better way? Yes, there is: Burton Unions! The Burton Union is basically a scaled-up way of doing this that is not only more hygienic, but also essentially fully automated, at least when it comes to topping up the casks: yeast is ejected from the bunghole of not one, but several casks, through a pipe going upwards, ending up in a tray that is located on top of the casks. Any beer ejected with the yeast will end up on the bottom of that tray, from where it can run back into the casks.

Pressure (from the fermentation) and gravity do all the work here to keep the casks topped up. And this wasn’t just a British brewing secret, German brewers knew about this approach, too.

Of course, they knew about it from brewing books and journals that also discussed British brewing, but it was nevertheless known.

In any case, Spundgärung is a technique that has completely fallen out of use in Bavarian brewing and German brewing in general, it is entirely historic. Burton Unions are probably the only system where this approach is still followed, at least the only one I know of, and they almost went extinct, too. So why not bring Bavarian top-fermented beers and Burton Unions together? It would be very interesting to see what impact the Burton Union system has on a Bavarian Weissbier: will it change the typical clove and banana aromas of the finished beer? Does it have any impact on the clarity of the beer?

Sure, Thornbridge announced that they will produce a version of Jaipur on it, and intend to use it for some of their other beers, then new recipes specifically designed for it, and of course, collaborations. A lot of it will probably be traditional British styles, because it’s traditional British brewing equipment.

But for me, trying a Bavarian Weissbier, fermented the old Spundgärung way, would be the most exciting and a project I would absolutely love to see.