2024 was an exciting year. For the first time, I was invited to speak at a conference about one of my favourite topics, Vienna Lager, and not just at one conference, but actually two. First at Heimbrau Convention (HBCon) in Romrod back in March, and most recently, at Sympozjum Piwowarów in Kraków, Poland.

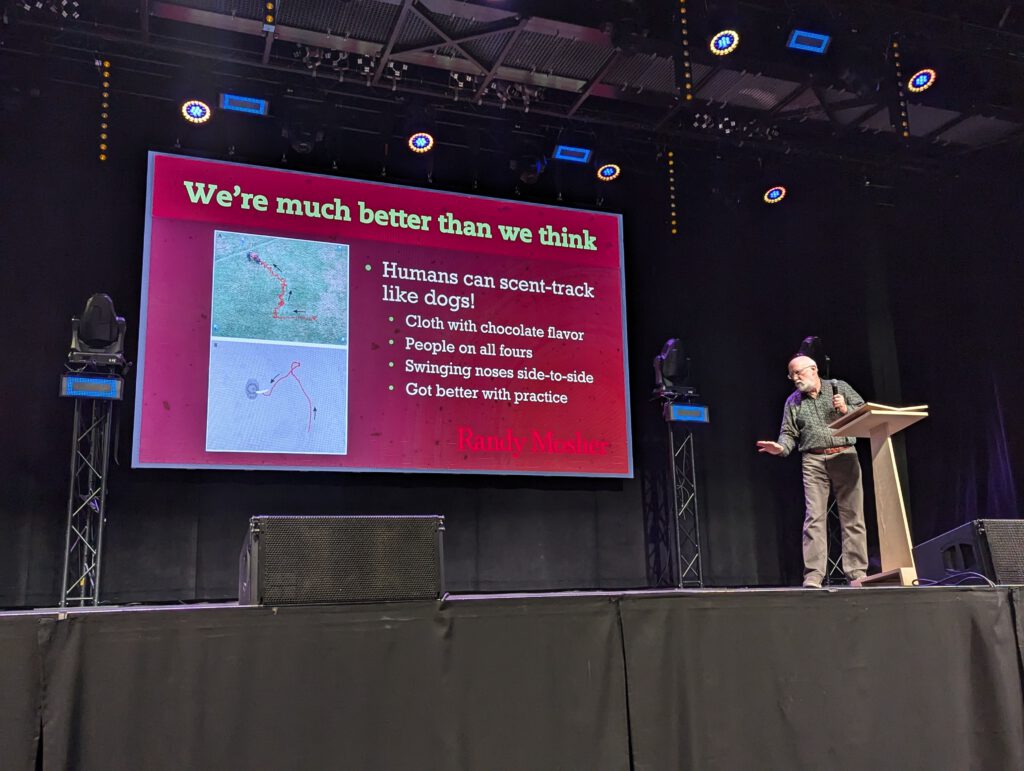

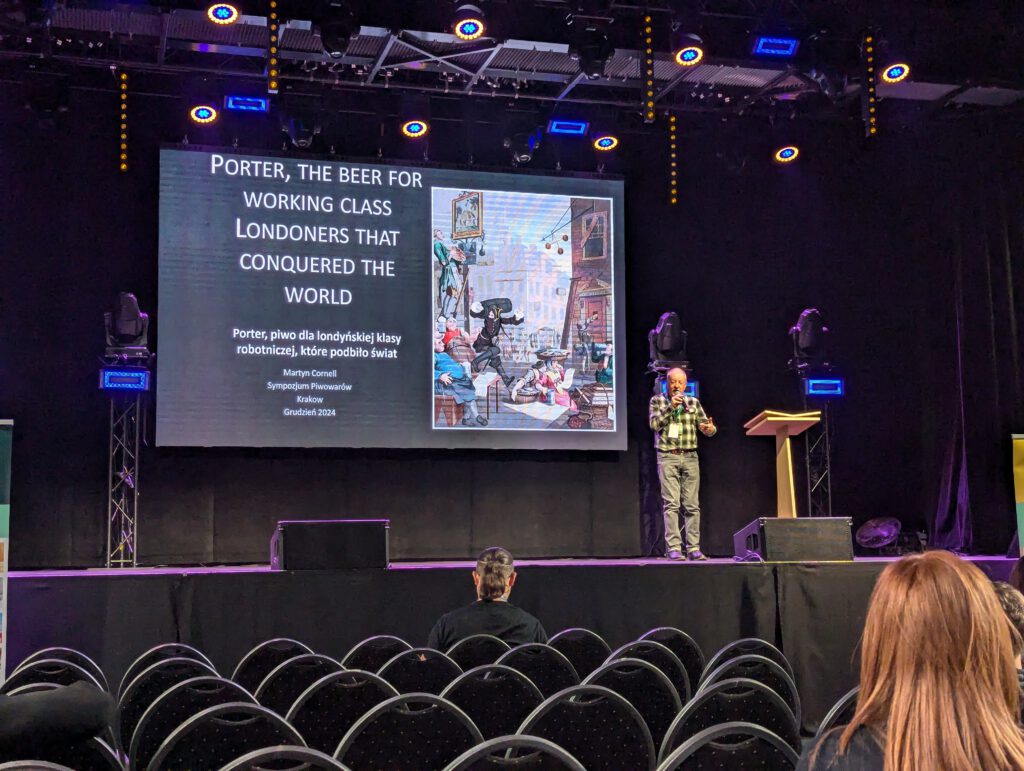

Beyond just talking about Vienna Lager, both events were great: at HBCon, I learned everything there is to learn about brewing beer like Mönchsambacher Weihnachts-Bock which I then used later on in a home-brewed Franconian-style Kellerbier, drank lots of excellent home-brewed beers, and met up with lots of other homebrewers, while in Kraków, I got to meet people from the Polish craft beer scene as well as see a few super interesting talks about the history of Porter, the latest brewing trends in the US, and a rather enlightening introduction to the human sense of smell and taste.

I also managed to go to Bamberg 3 times. First, as a farewell to a good friend and beer aficionado who moved from Berlin to Bishkek earlier this year but had never been to Franconia before; then to celebrate my good friend Ben‘s 30th birthday by doing a crazy day trip where we took the first train in the morning from Berlin to Bamberg, went all over Bamberg, and then went home on the last train; and finally, as a place to stay and visit BrauBeviale, the annual brewing and beverage industry fair in Nuremberg. For a slight change, we ventured a bit further out and did a day trip to visit the breweries Hummel and Wagner in Merkendorf and Höhn in Memmelsdorf, followed by a leisurely Frühschoppen trip to Zur Sonne in Bischberg the next day, all breweries we had not been to before that were easy enough to reach by public transport (if you pre-plan your trip a bit).

For my 40th birthday, my wife got me a two week trip to the US, which we of course used as a beery holiday and as an opportunity to meet people we had previously only known or talked to online or heard of their beers. Our main stops were Chicago, Austin, and Boston, with visits to Dovetail, Goldfinger, Live Oak, Notch and a few more. It’s safe to say that the American craft lager scene is very strong and is brewing tasty, diverse beer at a high technical level, combined with an incredible enthusiasm for the products they create.

And at the beginning of October, I even managed to visit Oktoberfest and the Augustiner tent on the festival’s very last day.

On the beer writing side, I did not manage to get any new big projects started, but I was nevertheless productive: in 2024, I wrote and published 31 blog posts (including this one), adding up to more than 31,000 words. In terms of page views, these are the top 5 most often read articles of 2024 that I wrote in the same year:

- Why Augustiner’s new alcohol-free Helles is a big deal

- How To Brew Mönchsambacher Weihnachts-Bock, according to the brewmaster

- My Summer Beers for 2024

- Alcohol-Free Augustiner: The Tasting

- Liquid yeast: why do I even bother?

I was a bit surprised to see just how popular my blog posts about Augustiner’s new beer, an alcohol-free Helles, had gotten, but then, non-alcoholic beers with ≤ 0.5% ABV have been the big new trend in 2023 and 2024, with overall quality of beers massively improving compared to 5, 10, 20 years ago. At Oktoberfest, I then experienced the new Augustiner beer in its absolutely best state: properly cold and served fresh on draught by the liter, it is a delight that is virtually indistinguishable from the regular strength beer. I didn’t miss the alcohol in the beer, because it didn’t feel like it was actually missing, and there were none of the off-flavours typical for alcohol-free beer that would have reminded me of the fact what I was drinking.

But the actual number one most often read blog post this year was not even written in 2024, but rather A Very Biased Guide To Berlin Beer and Pubs, October 2023 Edition, which is now responsible for more than 30% of all the page views on my blog.

Cheers to that! And while I don’t have any other big beer history project lined up, I still have a few more interesting topics that I want to further research and discuss in this blog. Watch this space.