The last time I blogged about Vienna lager, I wrote down everything we know about the historic specifications of the beer style and how it was brewed in the last few decades of the 19th century. The only point that was speculation on my side was the water profile. I can now say that this has changed (kinda), because I found a source quantifying the chemical compounds in the brewing water of the Klein-Schwechater brewery.

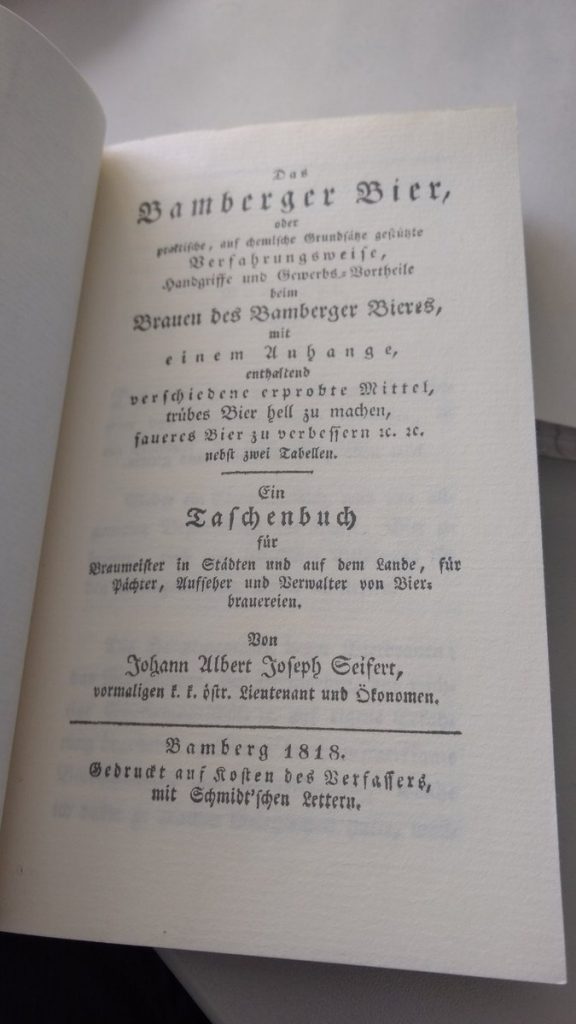

By pure accident, I stumbled upon an analysis of the brewing water (well water) of the brewery in Klein-Schwechat, in the book “The Theory and Practice of the Preparation of Malt and the Fabrication of Beer, with Especial Reference to the Vienna Process of Brewing” by Julius E. Thausing. It’s actually the English translation of a German book. One problem with the analysis is that it doesn’t specify any units for most of the numbers. It does specify the amount of residue after the water has been evaporated (in grams), but that was it. Unlike the English translation, the German original at least references the original source other than just specifying the author, Lermer. The original source for this analysis is Dingler’s Polytechnisches Journal, volume 187.

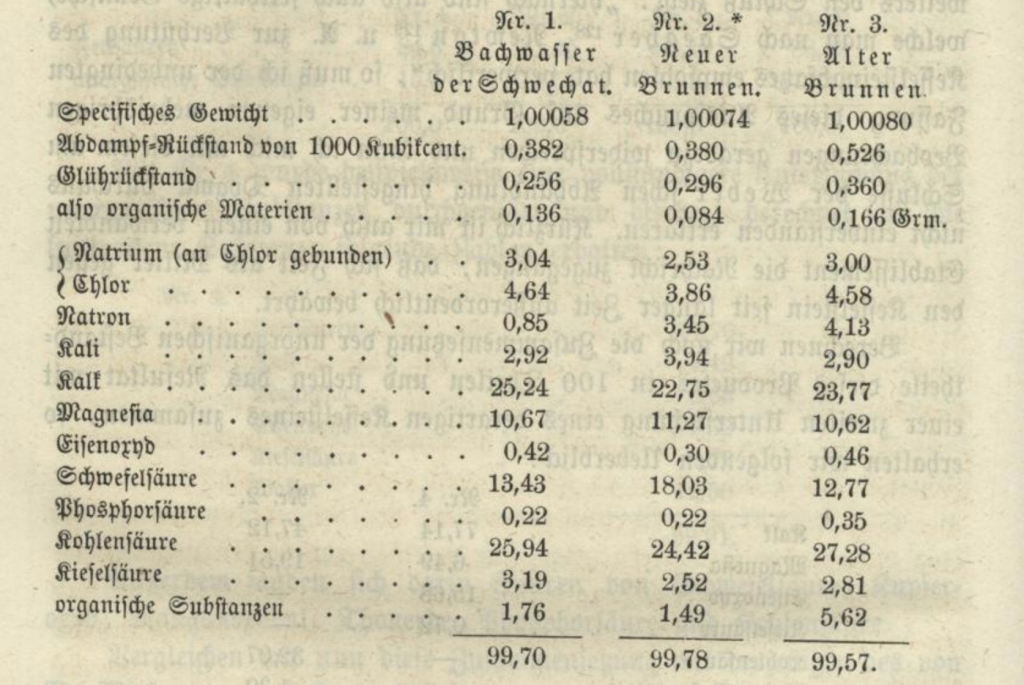

This journal apparently has quite a bit of history. It was founded in 1820 by chemist Johann Gottfried Dingler, was published for 111 years, and covered all topics from agriculture, mining and metallurgy to machine construction, chemistry, geology, electrics, and many more subjects. For the history of engineering and technology, it is a great source. Fortunately, all of its volumes have been digitalized by Humboldt University in Berlin, and published online. So of course, we also have the original source of the water analysis available. You can find it here. Even though the original source is more detailed, and not only contains the water analysis of the brewing water of Klein-Schwechat but also water analysis of the old well and the river Schwechat, it is not in any way clearer regarding units than what we had in the English translation of Thausing’s book. At least we do learn that Klein-Schwechat brewery had two wells, an old one and a new one, and at the time of the article’s publishing, all brewing water was taken from the new well, which is the analysis that has been reprinted by Thausing.

So by itself, the analysis is unfortunately not really helpful. If anybody knows how to interpret the numbers, I’m grateful for any help with it.

As for the author of the analysis, Johann Karl (Carl in some sources) Lermer is quite the interesting person himself. He was hired in the 1860’s by Anton Dreher as brewery technician but apparently quickly rose the ranks and became head of Dreher’s Trieste brewery. In the Polytechnisches Journal, he published a number of articles. Given his background as conducting analyses at Dreher’s breweries, it gives an interesting insight into what were technical subjects industrial-scale lager breweries at that time were concerned about: chemical analysis of Lupulin, analysis of barley malt sprout, the issue of beerstone in pipes, the issue of mold in wooden fermenting vessels, the effects of freezing beer, malting experiments, or chemical analysis of hot break. A complete list of his contributions can be found here.

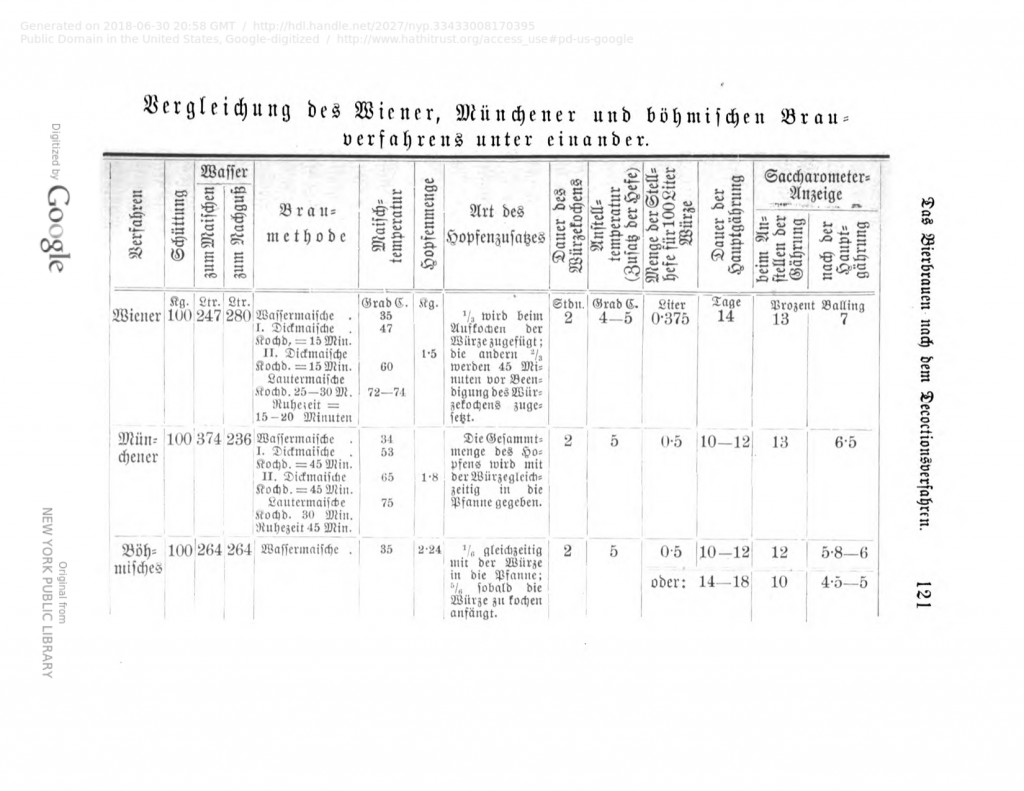

Besides the theoretical side, I’ve also been active on the practical side of Vienna lager brewing. Recently, we brewed a Vienna lager reasonably close to the historic specifications, with an OG of 13.4 °P (historical sources say 13 to 13.25 °P, the difference is due to a slighter greater mash efficiency), and 4.5 °P FG (which is close to the 4 to 4.25 °P you see in some historic sources), from 100% Vienna malt. One modification I made was the use of a double decoction mash instead of the more traditional triple decoction: I dough in at 38 to 40 °C and take a huge first decoction that brings temperature up to 65 °C. That way, the only protein rest is very briefly happening when heating up the first decoction. The second decoction then brings the temperature to 72-75 °C. That way, I skip an extensively long protein rest which wouldn’t exactly be productive with modern malts. I also deviated slightly from the hopping schedule, and only had one hop addition. I also made a slight mistake: my recipe in BeerSmith still had 3% alpha acid set for the Saazer hops, and I forgot to compensate for the 4.2% alpha acid Saazer hops that I had bought. So instead of 30 IBU, the resulting beer now has roughly 40 IBU. Oops.

Nevertheless, the outcome is nice: after 3 weeks of fermentation and many more weeks of cold lager, it’s just finished carbonating in the bottle and ready to drink. The bitterness is nicely counter-balanced with the residual sweetness coming from the low attenuation of the WLP820 lager yeast. Personally, I’m perfectly fine with the higher bitterness, even though it doesn’t 100% hit the original specs of the historic style. Even at 30 IBU, the beer would have enough bitterness to work nicely enough with sweetness. The 100% Vienna malt bring enough own malt flavour without making the beer cloying. All in all, not only a good example for the style, but also a reminder that for some beer styles, process is at least important as the careful choice of ingredients.